Guest Post by Kevin B. Johnson

How could American History bother conservatives?

Most people probably believe that sex education and evolutionary biology are the most contentious subjects taught in school.

But conservative activists have also targeted American history. Why? Because as historians such as Jon Zimmerman and David Blight have argued, America teeters on a culture-war divide in its understanding of its own history; a culture-war divide no less contentious than questions about sex and God.

Nowhere has this battle over the nation’s history been more bitter or grueling than in Mississippi.

A look at the record of conservative activism in the Magnolia State may shed some light on the continuing battle over the nature of history. It also demonstrates the ways conservatives have scored their greatest successes. In Mississippi, at least, conservatives managed to win by promoting one central idea: historical knowledge, properly understood, is static and unchanging.

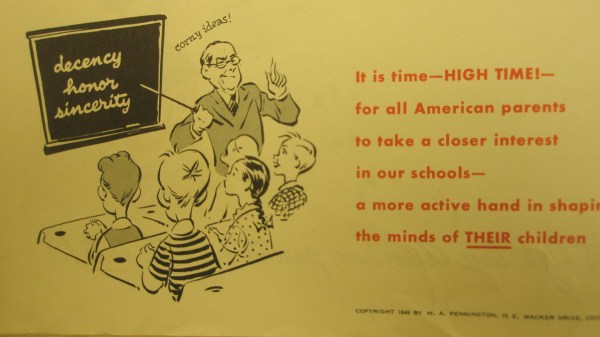

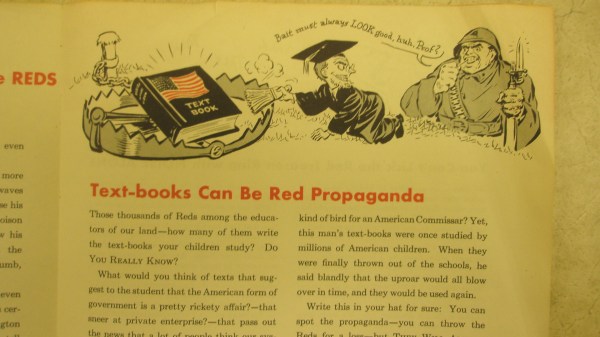

As the Cold War split nations into the Free, Unfree, and Third Worlds, Americans began scrutinizing their communities in search of suspected communists and subversives. In Mississippi, these searches involved the content in state-approved social studies textbooks. Civic-patriotic organizations such as the American Legion, the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR), the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), and the Mississippi Farm Bureau Federation led the charge in exposing objectionable historical knowledge presented in social studies texts.

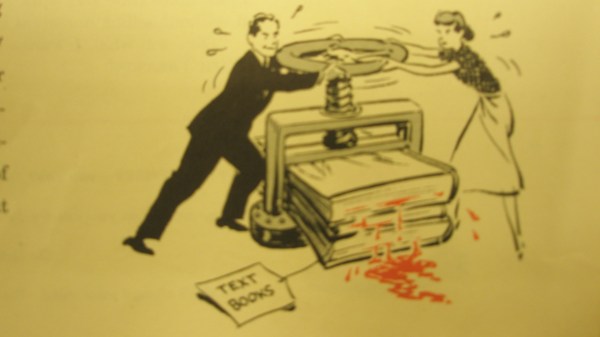

The civic organizations were not alone in controlling textbook content. In the 1940s Mississippi began providing students with schoolbooks; lawmakers also set up the State Textbook Purchasing Board charged with governing the screening and selection of all texts. In the Cold War context, however, many civic organization leaders believed the state’s education professionals were ill-suited for this job and challenged their role in screening school materials.

A few key figures spearheaded the effort to guard historical knowledge. Mississippi State College education professor Cyril E. Cain, for example, found reading and “doing” history to be a mystical-spiritual experience. In 1949, Cain learned about the California SAR calling for removal from that state’s schools the Building America textbook series. America and its democratic system was not part of a process, the SAR argued. Rather, American democracy had been built and perfected in comparison to rival governments.

Through the Mississippi Patriotic Education Committee, Cain called upon other conservatives guard against the historical knowledge contained in schoolbooks. He wrote to the state regent of the Mississippi DAR—Edna Whitfield Alexander, asking for collaboration between their two organizations “for the common cause of defending America” from textbook authors who espoused “alien ideologies.”

For the next twenty years, Alexander became the South’s preeminent textbook activist. She developed her organizational skills through the Mississippi DAR, which held significant power in the 1950s and 1960s. Many DAR members’ husbands served in state government or were the state’s business leaders; the DAR owned numerous radio stations throughout Mississippi. A segregationist society like other civic clubs, its members naturally opposed perceived egalitarian messages in textbook treatments of history, civics, and economics. History was the DAR’s domain and it held what they believed was magnificent power to order present-day society.

Gaining the attention of Mississippi’s leaders, especially Mississippi House Speaker Walter Sillers, Jr, by 1958, Alexander and DAR activists officially recorded their objection to the content in dozens of state-approved books.

The following are just a few examples:

“Laconic treatment of the South…did not mention Fielding Wright as Vice-Presidential nominee of the States Right party…praises Federal aid to education…Booker T. Washington picture is much later than Thomas Jefferson [sic]” –review of United States History, American Book Company, 1955 reprint.

“This slanted-against-the-South book makes no mention of the fact that Russia offered to help the North [during the American Civil War]” –review of The Making of Modern America, Houghton-Mifflin, 1953.

“…records a good bit of history—some of which we are not too proud, and conspicuously omits some of which we are very proud like religious freedom!” –review of Your Country and the World, Ginn & Company, 1955.

“…advocates creation of a state of social equality…” –review of Economic Problems of Today, Lyons and Carnahan, 1955.

“Formerly history was largely concerned with kings, monarchies, laws, diplomacy, and wars…Today history deals with the entire life of a people. So now were are told that history must change along with this changing world and George Washington, Valley Forge, and the U.S. Constitution are no longer worthy of recognition to be ignored so far as our children’s history books are concerned.” – wrote a DAR reviewer of The Record of Mankind, published by D. C. Heath, 1952.

The DAR, in addition, opposed books citing renowned scholars such as Henry Steele Commager, Charles Beard, Allen Nevins, Gunnar Myrdal, Arthur Schlesinger, John Hersey, in addition to Mississippi writers like Hodding Carter, Ida B. Wells, and William Faulkner.

These comments sent to Sillers demonstrate the DAR’s view of History. In the DAR vision, History should be dominated by pro-South, segregationist, and patriotic biases. The reason for teaching history in the Cold War context, the DAR and others agreed, was to instill in school children loyalty to state and country.

The DAR, under Alexander’s leadership, began a concerted lobbying effort. In 1959, Alexander informed the Mississippi Superintendent of Education and head of the State Textbook Purchasing Board, Jackson McWhirter “Jack” Tubb, that “youth must be taught Americanism in its purest form if this Republic is to survive.”

The American Legion and the Mississippi Farm Bureau Federation became important DAR allies. These civic clubs conducted official studies of Mississippi’s approved books and found that many “cater to alien ideologies contrary to the Mississippi way of life.” Boswell Stevens, a Legionnaire and president of the state’s Farm Bureau, believed social studies curricula should cultivate among students adoration of quintessential American values like Jeffersonian individualism, capitalism, and patriotism.

During state elections in 1959, the lobbyist coalition collaborated by staging exhibits of objectionable texts in the lobby of the Robert E. Lee hotel in Jackson. After Sillers intervened the DAR moved the exhibit to the lobby of the state capitol in time for the 1960 legislative session.

Lawmaker-members of American Legion and the Farm Bureau dominated the Legislature, passing amendments to state laws pertaining to textbook screening and adoption. The amendment gave the governor, recently elected Ross Barnett, appointment power over the state’s education professionals on these important textbook screening committees.

These conservative victories were not unopposed, however. Newspapers editorials considered the DAR efforts as a “witch-hunt” and the state’s teachers association believed that textbook reviews were best left to education professionals.

But politics—in this case, staunchly conservative politics—trumped the claims of journalists and teachers. Conservative activists also managed to stymie complaints from academic historians. In 1975, for example, James W. Loewen and several co-authors of the history text Mississippi: Conflict and Change had to file a federal lawsuit against Mississippi for adoption of their revolutionary new textbook. Loewen even commented at the time that most of the state-approved books were merely “didactic chronologies.”

Loewen’s lawsuit demonstrated the deeply entrenched nature of conservative visions of History in Mississippi. For decades, conservative activists had succeeded in establishing state sanction for their vision of History: a static, unchanging field of facts, uniquely useful for promoting patriotism and instilling a love for traditional Americanism.

Kevin Boland Johnson is a doctoral candidate in American history at Mississippi State University and a dissertation fellow with the Spencer Foundation. His dissertation, “The Guardians of Historical Knowledge: Textbook Politics, Conservative Activism, and School Reform in Mississippi, 1928-1988,” explores numerous education reform efforts designed either to constrain or improve public school social studies curricula. You can reach Kevin at kbj41@msstate.edu.