Teachers! Has anyone NOT heard this ugly phrase at some point? It’s everywhere. We see it in every new TV show about schools. I’m also finding heavy doses of it in the archives as I work on my new book. For hundreds of years now, the myth has not gone away. And it fuels America’s worst impulses.

From season 2, episode 1: No matter how good the snacks, students just don’t show up

Consider a few examples. These days, when I’m not in the archives, I’m watching Insecure on TV. It’s great. The main character, Issa, works for a non-profit that tries awkwardly to provide educational resources for low-income Black and Latinx students. In season 2, episode 1, she and her co-worker try desperately to bribe students to attend their afterschool tutoring session. At first, when the students do come, they only steal the snacks and run away. What is Issa supposed to do? She can’t help kids with their Geometry if they won’t show up.

Every teacher could tell similar stories. How is it possible—every teacher ever has asked—how is it possible to teach kids who don’t come to school? How can we beef up resources for kids whose parents don’t come to parent-teacher conferences?

Here’s the worst news—there has never been a time when this WASN’T the case. As I’m finding in my current research, two hundred years ago African-American leaders had a very difficult time convincing African Americans in New York and Philadelphia to send their children to the cities’ free schools. As The Reverend Peter Williams preached to the African-American congregants of St. Philip’s in New York City, April 27, 1828, free public schools were available for African-American students, but only a fifth of the city’s eligible black kids attended. As The Rev. Williams exhorted,

Brethren, if any of you have children that are not at school, do send them, and if you see any coloured children in the city, that are not receiving the benefit of an education, do use your influence with their parents, to have them sent to these fountains of wisdom. By so doing you will serve the interests of the community at large, and the interests of your immortal souls. It is a work of that Divine charity, which greater than, either faith or hope, never faileth, and covereth a multitude of sins.

Even back then, there were plenty of low-income families who just didn’t seem to value school. This long and sad history has led some people to a tragically mistaken conclusion. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I’ll bet dollars to donuts every teacher out there has come across it at some point in our careers. We’ll be wondering how to bridge this gap between school and family, and someone will say knowingly, “Some people just don’t value education.”

The implications are clear and they are terrible. The suggestion is that lower-income families, especially non-white ones, don’t put much emphasis on school for their children. The second implication is worse. It is as if teachers are telling one another not to bother TOO much, because no matter what, some families just don’t care.

Anyone spending two seconds in the archive will see that this cynical bit of teacher lore is utterly untrue. It’s just not true that low-income people don’t value schools. Historically, African Americans have always gone to extreme lengths to provide schools and education for their children. In Providence, Rhode Island, for example, a group of African Americans banded together in 1819 to build a schoolhouse for their children. It was burned down twice, but the families persisted. As one (white) sympathizer commented,

The active zeal evinced by many of the people of colour, in the town of Providence, to provide a place for the education of their children, and the public worship of GOD, is, in our opinion, exceedingly laudable, and worthy of the liberal encouragement of all good people. . . . The people of colour in this town, raised among themselves about five hundred dollars. Their Christian friends, sensible that too little attention had been paid to this class of community, cheerfully assisted them by their prayers and advice.

The dedication and devotion of countless real-life communities like the one in Providence raises a difficult question. Namely, if parents and communities were so dead-set on providing schools for their children, no matter what the obstacles, then why did African Americans who had access to free schools in New York and Philadelphia not take advantage of them?

I’ve found a couple of clues during this research trip. Consider, for example, the conclusion of one New York African American writer. This anonymous person wrote in the African-American newspaper Freedom’s Journal (March 30, 1827) that African-American kids should stay in school, even though, as the writer put it,

Is it asked [sic], What avails it, that we educate our children, seeing that having bestowed every attention in our power to meet this end we find them excluded from patronage suited to their attainments? I answer, Persevere in your efforts, and when our too long neglected race, shall have become proportionally in and informed with the white community, prejudice will and must sink into insignificance and give place to liberality and impartiality.

In other words, African American families in 1827 were asking why they should send their children to free schools, when no good jobs awaited at the end. Why should they persevere, if there were nothing but fake promises of “liberality and impartiality” at the end? The writer hoped that prejudice would evaporate, but I’m guessing plenty of families were not so sanguine.

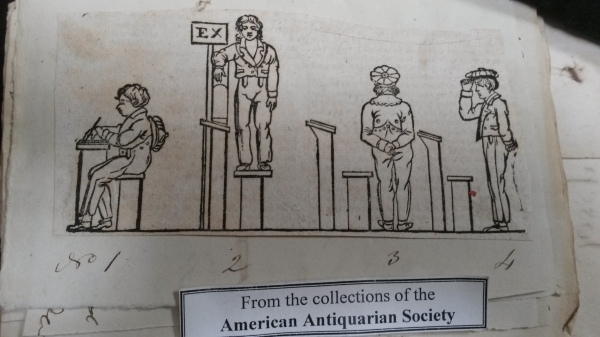

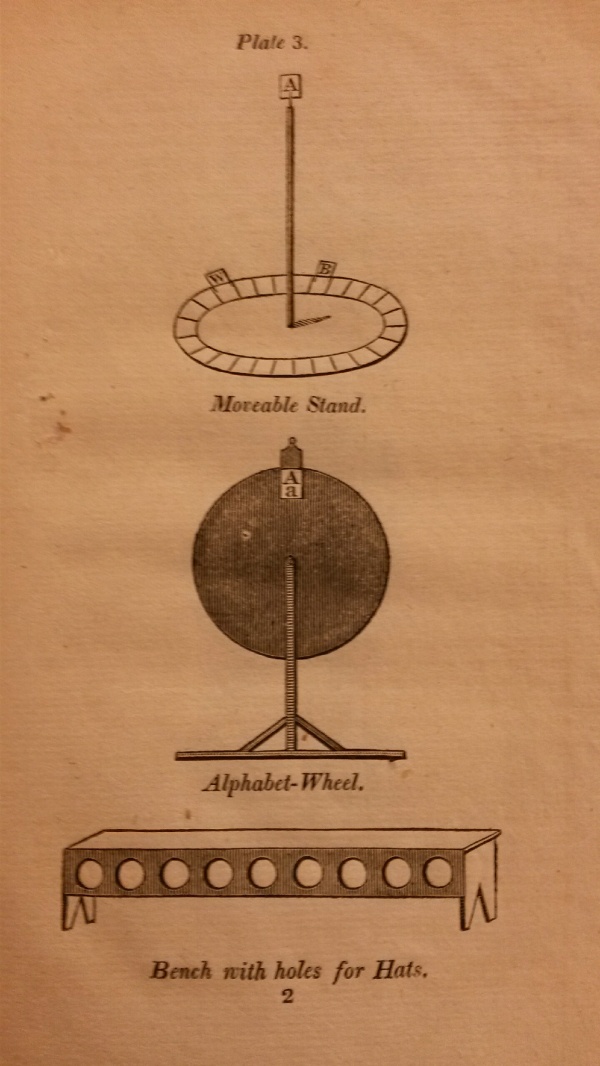

Moreover, they must have wondered why they should send their children to schools where the teachers often resorted to humiliating punishments, including hanging logs around the necks of children and shackling children together to march around the classroom. After all, those were the recommended punishments in the Lancasterian schools in America’s cities. As school reformer Joseph Lancaster admitted, when some people saw his schools in New York and Philadelphia, they protested that

the apparatus of logs, shackles, caravans, &c. were all implementations of slavery.

It’s not hard for me to imagine an African American family in 1827 wanting to avoid a school that punished children in the “apparatus” of slavery. Nevertheless, as the stories from Providence and elsewhere make abundantly clear, African American families have always made incredible sacrifices—and taken incredible risks—to provide schools for their children. They just don’t want to send their children to schools that humiliate their children for no good reason. They don’t want to send their children to schools that don’t prepare them for jobs at the end.

So…are there people who just don’t value education? Probably. There have got to be parents—rich and poor, black and white—who simply can’t be bothered to care too much about their children’s welfare. But it is not true and it never has been true that certain types of people–lower-income, non-white Americans–just don’t care. To the contrary, historically African-American communities have gone to great lengths to overcome legal and extralegal opposition to their schools.