They’re out there. In spite of decades of talk about “Godless” public schools, there are plenty of Christian teachers who see their work as a missionary endeavor. That ain’t right, but conservative Christians aren’t the only ones to use public schools to spread religious ideas.

As a new cartoon from young-earth creationism ministry Answers In Genesis makes clear, lots of conservative Christians like the idea that public-school teachers will do their best to preach the Gospel as part of their jobs.

Heroic missionaries in our public schools?

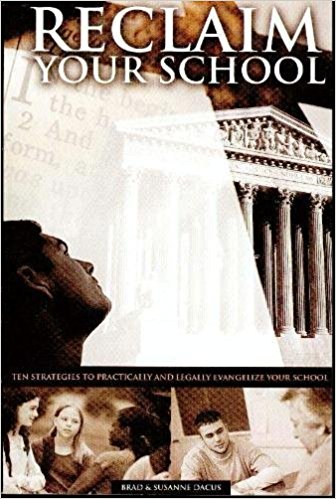

The creationists at AIG are certainly not alone in their celebration of public-school missionary work. At the conservative Christian Pacific Justice Institute, for example, Brad and Susanne Dacus encourage teachers to evangelize on the job. As Marc Fey of Focus on the Family writes about their work, it will help teachers spread the Gospel in “one of the greatest mission fields in our country today, our public schools.”

This sort of missionary vision for America’s public schools has a long history. Going back to the 1940s, groups such as Youth For Christ worked to get old-time religion into modern public schools. Beginning in 1945, as the idea of the “teenager” took on new cultural clout, YFC founder Torrey Johnson hoped to make YFC a group that would speak in the language of the new teen culture. As he explained to YFC missionaries, young people in the 1940s were

sick and tired of all this ‘boogie-woogie’ that has been going on, and all this ‘jitterbugging’—they want something that is REAL!

As early as 1949, YFC leaders such as Bob Cook argued that “high school Bible club work [was] the next great gospel frontier.” As he put it, YFC must aggressively evangelize among secular public high school students, since “atomic warfare will most certainly finish off millions of these youngsters before routine evangelism gets around to them.” By 1960, YFC claimed to have formed 3,600 school-based Bible clubs in the United States and Canada.

By 1962, these ad-hoc Bible clubs had been organized into a YFC program known as “Campus Life.” Campus Life included two main components, outreach to non-evangelical students and ministry to evangelical students.

In order to engage in this public school evangelism, national YFC leaders told local activists they must “invade the world where non-Christian kids are.” As an operations manual for Campus Life leaders warned its readers, their first entry into that hostile territory could be frightening. It described common feelings among YFC evangelists on their first approach to a public high school:

There it looms—a huge, humming, hostile high school. Hundreds, thousands of students, a professional corps of teachers and administrators, all busily turning the wheels of secular education.

To you, it’s a mission field. It has masses of kids who need spiritual help, even though most of them don’t know it. You and the Lord have decided to invade that field through the strategy called Campus Life.

This missionary attitude about public schools has also had a long and checkered history among creationists. Writing in 1991, for example, Henry Morris of the Institute for Creation Research called public schools “the most strategically important mission field in the world.”

As have other conservative Christians and creationists, the ICR repeatedly described public schools as unfairly biased against Christianity. As Henry Morris’s son and intellectual heir John D. Morris put it, “today’s public high schools and state universities are confrontational to the creationist student.” Aggressively secular teachers, John Morris warned, “take it upon themselves to ridicule Christianity and belittle and intimidate creationist students.”

Throughout the 1980s, ICR writers described the double impact of their missionary work in public schools. First, it would protect creationist kids from secularist hostility. Second, it could bring the Gospel message of creationism to students who would not hear it elsewhere. Missionary teachers had a unique opportunity. In 1989, one ICR writer explained it this way: “As a teacher,” he wrote, “you are a unique minister of ‘light.’ Your work will ‘salt’ the education process.” Similarly, in 1990 John Morris argued that the greatest hope for a decrepit and dangerous public school system lay with “Christian teachers who consider their jobs a mission field and a Christian calling.”

Every once in a while, you’ll hear young-earth creationist activists insist that they do not want to push creationism into public schools. But they certainly do want to make room for creationism. They hope to use public schools as a “mission field” to spread their Gospel.

They shouldn’t. But before we get too angry about it, we need to reflect on what this really means for our creation/evolution debates.

To folks like me, the most important value of public education is that it is welcoming to all students and families. It should not push religious values upon its students. It should not even imply that one sort of belief is proper and others are not.

As my co-author Harvey Siegel and I argue in our upcoming book (available in February!), the goal of science education must not be to indoctrinate children into any sort of belief about human origins.

Modern evolutionary science is currently our best scientific explanation of the history of human life. Therefore, we need to teach it in science class, unadulterated with creationist notions of design or supernatural intervention.

But too often, the implied goal is to free students from the shackles of their outdated religious ideas. Too often, the goal of evolution education is to change student belief about natural and supernatural phenomena. Progressive teachers like me sometimes slide into an aggressive ambition to help students see the world as it really is.

We shouldn’t. Not if students have religious reasons for believing otherwise. As I’ve argued at more length in the pages of Reports of the National Center for Science Education, too often evolution educators make the same mistaken “Missionary Supposition” that has tarnished conservative Christianity.

Are creationists in the wrong when they use public schools as a “mission field?” Definitely.

But they are not wrong because their religion is wrong.

They are wrong because public schools by definition must remain aggressively pluralist. They must welcome people of all religious faiths, and of none. In order for evolution education to move forward, we must all remember that public schools can’t promote any particular idea about religion, even the religious idea that young-earth creationism is silly.

Not only that, but public schools have a unique place in America’s vision of itself. For a long time now, as Jonathan Zimmerman explored, Americans have considered their local public school a central part of their community.

Not only that, but public schools have a unique place in America’s vision of itself. For a long time now, as Jonathan Zimmerman explored, Americans have considered their local public school a central part of their community.