What should good history teaching look like? As we’ve noted here at ILYBYGTH, conservative critics have warned that the new Advanced Placement US History framework pushes a “consistently negative view of the nation’s past.” Now, two big historical associations have defended the guidelines. But those associations are downplaying a central reason why so many conservative critics object to the APUSH framework.

Anyone with ears to hear can’t miss the conservative concern about the tenor of the new APUSH framework. From the Republican National Convention to the blogosphere to the stuffed-shirt crowd, conservative pundits have teed off on the new guidelines for the advanced history classes.

Time and again, conservative activists such as Larry Krieger have warned that the new guidelines leave out key documents such as the Mayflower Compact and teach children that America’s history is the story of white exploitation, greed, and genocide.

The National Council for History Education and the American Historical Association have published letters in defense of the APUSH guidelines. Mainly, these history groups insist that the new framework is not biased. As the AHA puts it,

The AHA objects to mischaracterizations of the framework as anti-American, purposefully incomplete, radical, and/or partisan.

The 2012 framework reflects the increased focus among history educators in recent years on teaching students to think historically, rather than emphasizing the memorization of facts, names, and dates. This emphasis on skills, on habits of mind, helps our students acquire the ability to understand and learn from key events, social changes, and documents, including those which provide the foundations of this nation and its subsequent evolution. The authors of the framework took seriously the obligation of our schools to create actively thinking and engaged citizens, which included understanding the importance of context, evidence, and chronology to an appreciation of the past.

But there is a minor theme in these defenses. In the snippet above, the AHA signatories mention that good history education goes beyond the “memorization of facts.” Similarly, the NCHE insists, “The point of education is not simply to acquire a specific body of information.”

But for many conservative activists and their supporters, the definition of education is precisely the acquisition of knowledge. And that definition has proven enormously politically powerful over the years. Please don’t get me wrong—I’m an ardent supporter and sometime member of both the NCHE and the AHA. But these letters downplay the culture-wars significance of what Paolo Freire called the “banking” model of education.

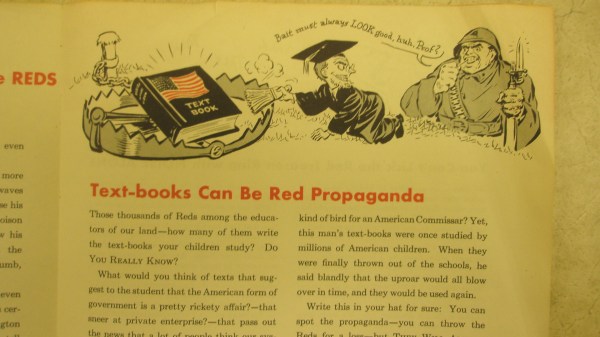

Not that conservative critics aren’t concerned with the partisan tone of the new guidelines. That is certainly a key motivating factor for many, I’m sure. But behind and beyond those worries lies a deeper conservative concern with the definition of education itself. Not all, certainly, but many conservatives want education in general to remain the transmission of a set of knowledge from teacher to student.

This notion of proper education is so deep and so profound that it often goes unarticulated. Conservatives—and many allies who wouldn’t call themselves conservative—simply assume that education consists of acquiring knowledge, of memorizing facts. And this assumption lurks behind many of the big education reforms of our century. The test-heavy aspects of the No Child Left Behind Act and the new Common Core standards rely on a notion of good education as the transmission of information. If a student has really learned something, the thinking goes, a test can find out.

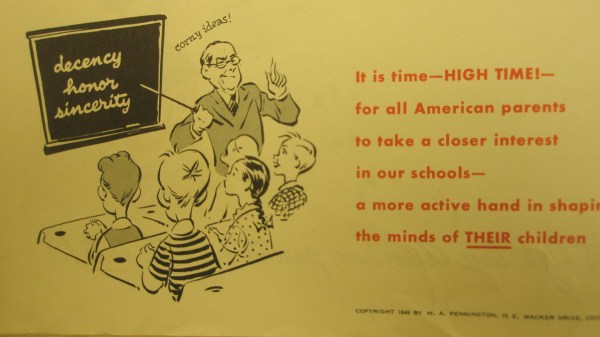

For over a century, progressive educators have railed against this powerful assumption about the nature of education. But for just as long, conservative activists have worked hard to keep this idea of education at the center of public schooling. As I argue in my upcoming book, conservatives have been able to rally support for this “banking” vision of proper education in every generation.

In the 1930s, for instance, one leader of the Daughters of the American Revolution defined education precisely as a body of ideas that “shall be transmitted by us to our children.”

And in his popular 1949 book And Madly Teach, pundit Mortimer Smith insisted that true education consisted precisely of transmitting the children “the whole heritage of man’s progress through history.”

Similarly, in 1950, an angry letter-writer in the Pasadena Independent insisted on the transmission model as the only proper method of education. As this writer put it,

Children have the right to learn by being taught all and more than their parents and grandparents learned—one step ahead instead of backward, through each generation.

Perhaps the most articulate advocate for this notion of traditional, transmissive education was California State Superintendent of Public Education Max Rafferty. In his official jobs and his syndicated newspaper column, Rafferty insisted that the only worthwhile definition of education was the transmission of knowledge from adult to child. Two fundamental principles of “common sense” in education, Rafferty argued in 1964, were the following:

-

Common sense told us that the schools are built and equipped and staffed largely to pass on from generation to generation the cultural heritage of the race.

-

Common sense took for granted that children could memorize certain meaningful and important things in early life and remember them better in later years than they could things that they had not memorized.

We could list a thousand more examples. This tradition among conservative activists has remained so powerful that it often goes without saying. And it lurks behind conservative agitation against each new generation of progressive educational reform.

So when groups such as the AHA and the NCHE defend the new APUSH guidelines, they should spend more time explaining and defending their notion that good education relies on more than just the memorization of facts. For many parents and teachers, the transmission of those facts is precisely the definition of good education.