I’m no conservative, but I respect several conservative thinkers and writers. We may disagree—sometimes fiercely—but folks such as Rod Dreher, Patrick Deneen, and Mark Bauerlein are always worth reading, IMHO. In education, I put Rick Hess in this category. In a recent piece about localism, though, Hess makes some mistaken claims about the history of educational conservatism. I can’t figure out why.

The first worry wasn’t desegregation, but communist subversion.

He’s not alone. Back when my book about the history of educational conservatism came out, I did a brief interview with conservative journalist John Miller. He wanted to know about the long history of conservative desire for charter schools. As I told him, there wasn’t one. The charter movement only became a darling of most conservative thinkers at the very tail end of the twentieth century. Before that, only a few lonely free-marketeers embraced Milton Friedman’s charter plan. (I have described this history in a different academic article, if you’re interested.)

Conservatives aren’t the only ones who don’t like to look their history square in the face, of course. Progressives don’t like to be reminded that WE were the racist ones back in the 1920s, as I also describe in The Other School Reformers.

Hess is too smart and too ethical to distort conservative school history in the usual ways. He frankly acknowledges that conservatives turned to localism in order to protect their right to racial segregation. As he and his co-author put it,

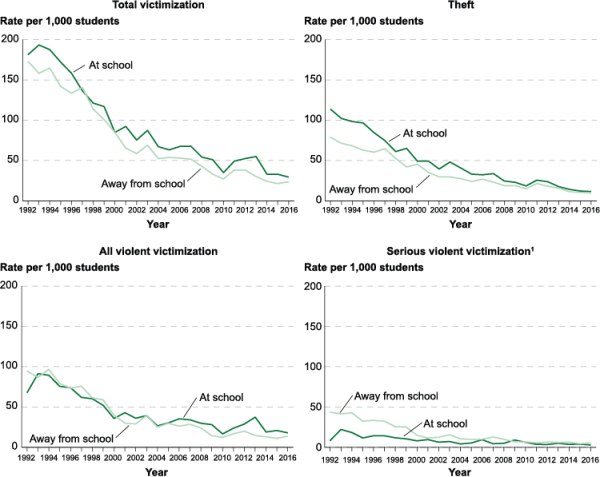

After Brown v. Board in 1954, demands for more “rational” and “less political” oversight were joined by a compelling moral claim—that many communities (and even states) could not be trusted to do right by all their students. Thus, the post-Brown era was marked by school reform agendas—in the states and in Washington—that frequently sought to reduce or even eliminate local control. These strategies came from both the right and left, from both legislatures and the courts, and included new directives regarding desegregation, standards, testing, discipline, funding, teacher quality, school interventions, magnet schools, school choice, and more.

In this telling, federal influence after 1954 pushed states and towns to desegregate. Conservatives pushed back, demanding local control in order to preserve segregated schools. In one sense, he’s not wrong. Brown v. Board marked a milestone in conservative thinking about schools and education. But 1954 was not the watershed year. For American conservatives, the big switch came earlier, in the New Deal era.

A later effort (1963), but wow.

Through the 1920s, leading conservative public figures tended to call for increased federal involvement in local schools. By the 1940s, conservatives recoiled in horror at the notion of federal control.

What happened?

It wasn’t Brown v. Board. Brown v. Board strengthened conservative animosity toward the idea of federal educational leadership a thousandfold. But it did not create that animosity. Starting in the 1920s, conservative thinkers and activists became convinced that the academic leaders of educational thinking had gone to the socialist dogs.

In the 1930s, conservatives mobilized against the “experts” at places such as Teachers College, Columbia University. As one business leader warned an ally in the American Legion in 1939, professors such as Harold Rugg and George Counts

have been weaning [sic] over to their side a large and increasing population of educational authorities. This ties in with the whole progressive-education movement, which is another thing which some of old-fashioned believers in mental discipline believe is helping to weaken the moral strength and self-reliance of our youth. That may not come under the heading of Americanism or un-Americanism, but it is a closely related consideration because the progressive educators and the spreaders of radical un-American doctrines are to a large degree the same people and they mix their two products together and wrap them up in one package.

For this patriotic conservative, the leading educational experts could no longer be trusted.

By the 1940s, it had become standard thinking among conservatives—all sorts of conservatives—that federal control meant leftist control. They warned one another that “they” were after your children. For decades, they investigated textbooks for subversive squirrels and other communist rats.

The trend was so powerful that organizations such as the National Association for Education tried to fight back. Federal aid to education, they told anyone who would listen, was nothing but a better way to fund local schools.

NAE: Don’t hate me cuz I’m federal… (c. 1950)

Conservatives didn’t buy it.

By the time SCOTUS ruled in favor of school desegregation, conservative thinkers and activists had long distrusted the influence of the federal government. They had long since turned to the idea of local control as the only way to protect decent education.

To this reporter, it seems today’s conservatives would want to trumpet this version of conservative educational history, not ignore it. I can’t help but wonder: Why don’t they?