It’s going to be a long wait until June. That is when we’re expecting the SCOTUS decision in Espinoza v. Montana. You might be sick of reading about this case by now, but here’s one more point to consider: Now is a good time for states to discriminate. Why? They need to discriminate against religious schools to avoid having to choose between good and bad religions.

First, a little background: The issue in Espinoza v. Montana is whether or not states can discriminate between religious schools and secular ones. A parent wanted to use voucher money to send her kid to a religious school. The state’s constitution prohibits state funding of religious schools. The state supreme court said no. SCOTUS now has to weigh in.

SAGLRROILYBYGTH might recall that the “baby Blaine” amendments are often called “bigotry” by Espinoza’s supporters. These amendments—like the one in Montana that prohibits tax money for religious schools—really WERE adopted in an effort to limit Catholic-school influence. However, as we’ve discussed in these pages, Blaine amendments also represented a long tradition of “anti-sectarian” attitudes for public schools.

Recently, Mark David Hall of George Fox University made the case for Espinoza. He acknowledges the emptiness of the “baby-Blaine” argument. As he notes, the 1870s amendment may have been fueled by anti-Catholic bigotry, but it was re-upped in 1972 without any shred of anti-Catholic animus. He concludes by asserting that there is no cause for leaving religious schools out of voucher programs. As he puts it,

States should not be able to discriminate on the basis of religion unless they have a compelling reason to do so, and there is certainly no compelling reason in this case.

I agree with the first half of this sentence but not the second. States should not discriminate without a compelling reason. But the history of the twentieth century makes it clear: Society does indeed have a compelling case to limit its public support for religious institutions.

Back in the 1920s, it was widely assumed that public schools must actively teach a generic, non-denominational Christian religiosity. For example, between 1913 and 1930, eleven states passed mandatory Bible-reading laws. (Massachusetts already had one on the books, from 1826.) These laws had enormous public support. They were often seen as teaching simple moral truths, not divisive religious practices. Advocates commonly claimed that such basic religious ideas were a necessary part of any healthy society. For example, President Calvin Coolidge wrote in 1927,

The foundations of our society and our Government rest so much on the teachings of the Bible that it would be difficult to support them if faith in these teachings should cease to be practically universal in our country.

Throughout the first half of the 1900s, most public schools continued the traditions of the 1800s. Public schools were supposed to be “non-sectarian.” At the time, that meant they should not teach specific, controversial ideas about baptism or priesthood. But they included practices that were seen as non-controversial, such as Bible reading and reciting the Lord’s prayer. Public schools often arranged for students to be pulled out of school to learn specific denominational religious practices.

Over the course of the twentieth century, though, Americans’ opinions about the proper role of religion in public schools changed. By 1963, when SCOTUS heard the case of Abington Township v. Schempp, Bible-reading and teacher-led prayer were no longer seen as non-controversial. What if a non-religious student felt excluded? Or a non-Christian one? Even if they were allowed to skip the prayer or the Bible?

In 1970, SCOTUS reinforced the new vision of the proper role of government in school religion. In Lemon v. Kurtzman, the court laid out its famous three-prong “Lemon test.” In judging complicated cases of schools and religion, the court ruled that any law must 1.) have a secular purpose; 2.) neither promote nor inhibit religion; and 3.) avoid “excessive government entanglement with religion.”

When it comes to Espinoza, the dangers arise from the overthrow of these Lemon rules. States like Montana do indeed have a compelling reason to leave all religious schools out of their funding programs. If they do not, they will have to decide which religious schools to include and which to exclude, or simply to include all religious schools.

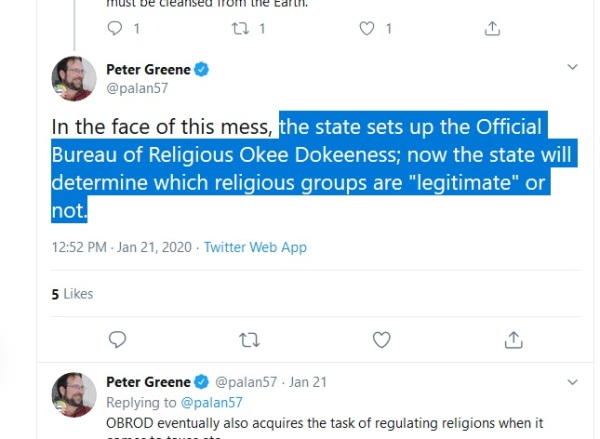

It seems too obvious to need elaboration, but neither religious groups nor state governments should want to put state governments in charge of choosing “legitimate” religion. As Curmudgucrat Peter Greene put it far better than I ever could, governments would need to establish

the Official Bureau of Religious Okee Dokeeness; now the state will determine which religious groups are “legitimate” or not.

If, on the other hand, states decide simply to include ALL religious groups in voucher programs, they will need to be prepared for the fallout. Certainly, that will include religions that endorse anti-LGBTQ ideas or racist ones. It will include religions that force brutal, even fatal “healing” services on children. It will also include churches of flying spaghetti monsters and Satan.

Is any state really ready for that?

They are not. We are not. I agree with Professor Hall that states should avoid discriminating against religious groups without a compelling reason. That might mean providing playground equipment for a religious school is okay. But when it comes to sending tax dollars to the actual religious schools themselves, states have a very compelling reason to avoid wading into religious wars.

Consider, for example, the policy of the Adelphi School in Philadelphia at the start of the century. All students were exhorted to follow basic rules of Christian morality and “strive to be good children by loving [their] HEAVENLY FATHER.” The school founders told parents—without seeing any contradiction—that the school would not teach any religion. It would only instruct the children in reading the Bible and following “Christian morality.”

Consider, for example, the policy of the Adelphi School in Philadelphia at the start of the century. All students were exhorted to follow basic rules of Christian morality and “strive to be good children by loving [their] HEAVENLY FATHER.” The school founders told parents—without seeing any contradiction—that the school would not teach any religion. It would only instruct the children in reading the Bible and following “Christian morality.”

We can only make sense of the violent response to Rugg’s textbooks if we put the story in this imaginary context. In the imaginations of many conservatives, Rugg’s textbooks were an immediate threat to American society as a whole. Destroying them was the only way to protect children from that imaginary threat.

We can only make sense of the violent response to Rugg’s textbooks if we put the story in this imaginary context. In the imaginations of many conservatives, Rugg’s textbooks were an immediate threat to American society as a whole. Destroying them was the only way to protect children from that imaginary threat. Again, seems like a startlingly violent reaction to a fairly humdrum textbook problem. Along the picket lines, however, activists were circulating flyers with shocking language. The quotations were purportedly from the offending textbooks, but the offensive language was not found in the actual adopted textbooks. In the imagination of the protesters, however, it seemed entirely believable that school textbooks in 1974 might really include offensive sexual language. They were willing to take extreme measures to protect children from these threats, even though the threats never really existed.

Again, seems like a startlingly violent reaction to a fairly humdrum textbook problem. Along the picket lines, however, activists were circulating flyers with shocking language. The quotations were purportedly from the offending textbooks, but the offensive language was not found in the actual adopted textbooks. In the imagination of the protesters, however, it seemed entirely believable that school textbooks in 1974 might really include offensive sexual language. They were willing to take extreme measures to protect children from these threats, even though the threats never really existed.

Will the impeachment investigation

Will the impeachment investigation