HT: MM

Would you fire a teacher if he did any of the following?

- Graphically described a sex act to his high-school class?

- Graphically described a homosexual sex act to his high-school class?

- Graphically described a submission/bondage sex act to his high-school class?

- Read a poem in class by one of the greatest twentieth-century American poets?

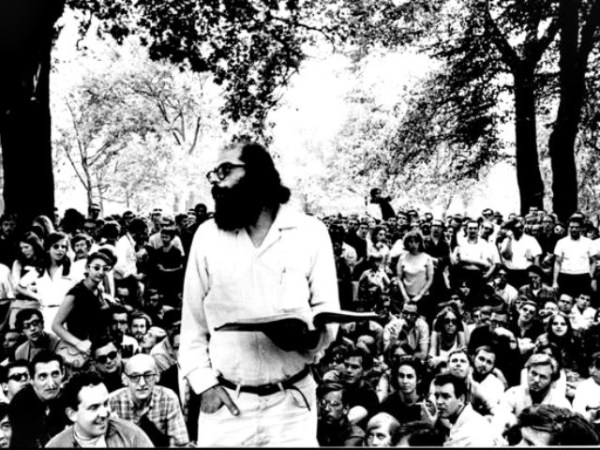

The trick, of course, is that the teacher in question did all of those things, and all at the same time. We read news from the wilds of South Windsor, Connecticut, where an experienced and award-winning teacher was pushed out of his classroom. His crime? Reading Allen Ginsberg’s 1968 poem “Please Master.”

The SAGLRROILYBYGTH will no doubt leap to the culture-war implications of this case. To my mind, Olio’s ouster raises a couple of issues of perennial difficulty. First, what are public schools supposed to be doing about sex? And second, are hippies heroes or villains?

As David Freedlander reports in The Daily Beast, David Olio had taught in the district for nineteen years. He had won awards for teaching excellence. On the fateful day in question, a student brought in the Ginsberg poem and asked if they could read it in class. Olio agreed.

The poem does contain some pretty explicit sexual language. It makes me uncomfortable to think about reading it to any group of people. More interesting, though, are the interpretations of Olio’s use of the poem. Progressives see it as a proper and even heroic act. Conservatives call it something else entirely.

As Freedlander argues from the progressive side, shouldn’t high-school students be reading such things? Students at that age are keenly aware of explicit sexual activities, even if many students have only vague and false notions of what they are. Is it not the point of a rigorous education to guide students through these difficult and controversial topics?

Or is this a question of sexual malfeasance? At Breitbart.com, Susan Berry pleads the conservative case against Olio. Using such “graphic gay sex” material in class, Berry believes, abrogates the “trust” parents place in public schools.

At the heart of such disagreement lurks a deep divide over the meaning of Allen Ginsberg himself. Was he a heroic boundary-pusher? Freedlander cites Ginsberg fan Steve Silberman. Ginsberg, Silberman insisted,

thought that by bringing material into poetry that were previously considered unpoetic, he enlarged the poetic occupation.

Or was Ginsberg only typical of 1960s sexual excesses? Conservatives might scoff at the notion that there is any true artistic merit in poetry that apotheosizes our most prurient sexual nature. As usual, conservative educational icon Max Rafferty expressed in 1968 some of the most memorable anti-hippie bon mots. He blasted the literary pretensions of “the lank-haired leaders of our current literati.” Too many hippie protesters, Rafferty insisted, “look as though their main grievance was against the board of health.” Young people needed more talk about sex, Rafferty believed, “about as much as Custer needed more Indians.” Instead, Rafferty thought, literary education should focus on the tried-and-true guides to basic morals such as bravery, self-sacrifice, and honesty.

At the heart of this case, it seems, we find some tangled culture-war history. As Andrew Hartman argues in his new book, the “1960s” serves as a flashpoint for continuing battles over morality and public policy. If Ginsberg is a Great American Poet, then it does indeed seem short-sighted to punish a teacher for exposing students to his work. If Ginsberg, on the other hand, was the dirty edge of a vapid adolescent “howl” of self-seeking hedonism, then teachers have a duty to protect children from such foul material.

What would you do? Would you punish this teacher for a sex crime? Would you perhaps forgive him for a momentary lapse in judgement? Or, on the contrary, would you reward him for engaging his class in a bold and inspired moment of curricular bravery?