Why is this so hard to get through our thick skulls? American schooling is not in the hands of progressive teachers and ed-school professors like me. It just isn’t. If we needed any more proof of it, take a look at the College Board’s decision to change its framework for the Advanced Placement US History course. As has always been the case, conservative complaints this time around have been about the implications and tone of classroom materials. My hunch is that many people wouldn’t see what the big deal was about.

Throughout the twentieth century, as I argued in my last book, American conservatives battled—and won—time and time again to control textbooks. Any whiff of progressive ideas was snuffed out before it could become the norm in American classrooms.

A set of progressive social-studies textbooks in the 1930s quickly became libri non grata after conservatives mobilized against it. In the 1970s, another set of progressive textbooks sparked a school boycott in West Virginia that caused a future secretary of education to speak out against progressive-type textbooks.

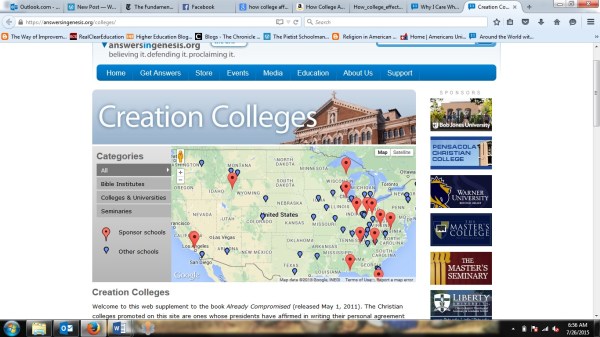

Now, according to an article in the Washington Post, the College Board has revised its framework for its AP US History class after ferocious conservative complaint. As we’ve discussed in these pages, conservative intellectuals and activists pushed hard to win this prize.

But here’s the kicker: I bet most casual readers of the new framework wouldn’t notice the differences. Now as in the past, the arguments are generally about tone and implication, rather than large-scale differences in content.

In the 1930s, conservative critics of Harold Rugg’s progressive textbooks admitted that most readers probably wouldn’t see the problem. Leading conservative critic Bertie Forbes called the Rugg books “subtly written” so that only an expert could notice the anti-American “insidious implication.” Another anti-Rugg leader warned that Rugg’s books were “very subtle,” not obviously anti-American, but packed with “weasel words” meant to subvert American values.

During the 1970s fight over textbooks, conservatives similarly admitted that a regular patriotic American reader might not see the problem at first glance. But as one conservative leader told an interviewer, the books were all bad, since they had been written with “the attitudes of evolution and all that.” Another conservative admitted that he did not even feel a need to read the actual textbooks. “You don’t have to read the textbooks,” he wrote.

If you’ve read anything that the radicals have been putting out in the last few years, that was what was in the textbooks.

Every time, conservatives have warned, it takes an expert eye to detect the problem with sneaky progressive textbooks.

This time around, too, conservative intellectuals protested against the tone and implication of the new history framework. As a group of leading thinkers wrote in their June protest letter, the rejected history framework

Is organized around such abstractions as “identity,” “peopling,” “work, exchange, and technology,” and “human geography” while downplaying essential subjects, such as the sources, meaning, and development of America’s ideals and political institutions, notably the Constitution. Elections, wars, diplomacy, inventions, discoveries—all these formerly central subjects tend to dissolve into the vagaries of identity-group conflict. The new framework scrubs away all traces of what used to be the chief glory of historical writing—vivid and compelling narrative—and reduces history to a bloodless interplay of abstract and impersonal forces. Gone is the idea that history should provide a fund of compelling stories about exemplary people and events. No longer will students hear about America as a dynamic and exemplary nation, flawed in many respects, but whose citizens have striven through the years toward the more perfect realization of its professed ideals. The new version of the test will effectively marginalize important ways of teaching about the American past, and force American high schools to teach U.S. history from a perspective that self-consciously seeks to de-center American history and subordinate it to a global and heavily social-scientific perspective.

The problem is not that the un-revised new framework didn’t teach US History. The problem, according to conservative thinkers, is that it taught history with a certain attitude, a certain approach.

Is the new framework more conservative? Leading intellectuals seem to think so.

Take the ILYBYGTH challenge: Read the revised framework for yourself. Does it seem “conservative” to you? Where? How? Can you find the differences in tone and approach that conservatives demanded?