Quick: What does the Bible have to say about vegetarianism? …about the war in Iraq? …about Catholicism?

I don’t know the answers to these questions. And, without meaning any disrespect, I can honestly say I don’t care. I don’t think my ignorance on these issues makes me “ignorant.” I don’t think it makes me uneducated. I just don’t think the Bible’s opinions on these issues are important. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not anti-Bible. In fact, I’m confident I’d be better off if I had spent my youth memorizing the Psalms instead of the lyrics to the Gilligan’s Island theme song. But I didn’t. And I don’t feel the loss.

Just sit right back and you’ll hear a tale…

However, many citizens of Fundamentalist America would consider my ignorance deeply embarrassing. For many conservative religious folks, especially among the Protestant denominations, the ability to cite Scriptural chapter and verse is one sign of an adequate spiritual education.

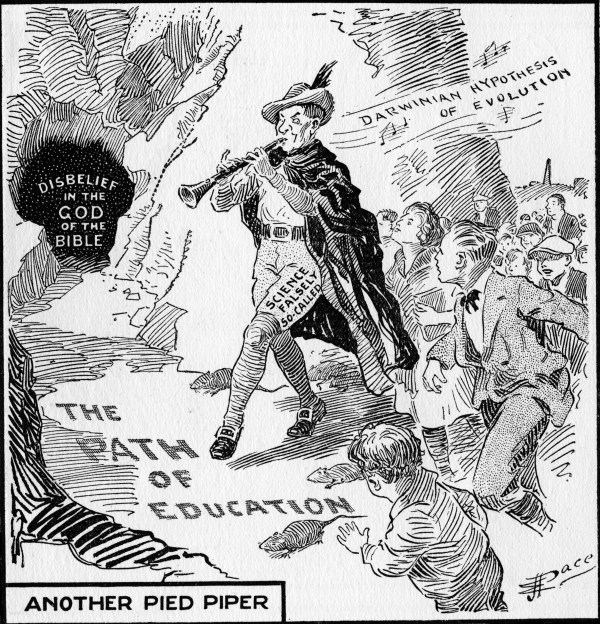

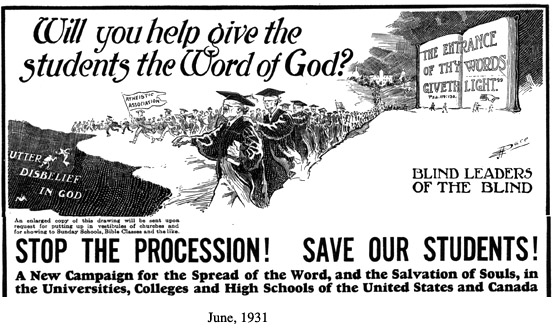

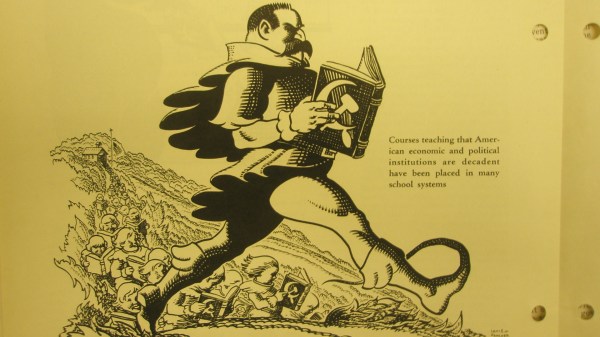

This divide fuels America’s culture wars. Many non- or anti-fundamentalists doubt that fundamentalists are even capable of rational, logical intellectualism. (Consider a few examples: here, here, here, here, and here.) The more ardently conservatives dig into their Bibles to prove their points, the more confident anti-fundamentalists become that conservatives have lost all claim to intellectual coherence.

And many fundamentalists don’t seem to understand that their compilations of Biblical proof-texts carry very little weight outside the borders of Fundamentalist America. They build arguments against homosexuality or same-sex marriage based on collections of chapter and verse. But such arguments are only compelling—or even comprehensible—if we accept the premise of the Bible proof-text in the first place. As a result, different sides do not speak to one another. They speak—or yell—past one another, scoring points that only the people on their own side can recognize.

If we outsiders are to understand Fundamentalist America, we need to understand the proof-text tradition. Why do religious conservatives care so much what Leviticus has to say about whether or not people should have sex with animals? Why is it so important that evidence for a young earth can be found not only in Genesis, but also in Mark 10:6, 1 Corinthians 15:26, and Matthew 19:4,5?

It is not a stretch to say that this style of proof-text argument had been, until the late 1800s or early 1900s, the standard style of theological disputation among Protestants. In the nineteenth century, European scholars began to look at the Bible in a new way. By the turn of the twentieth century, leading American Protestant theologians disputed the intellectual usefulness of the Scriptural proof-text. In 1907, for instance, William Newton Clarke lambasted his more conservative colleagues for their continued reliance on this method. “Even if,” Clarke argued, “a proof-text method were a good method in itself, it could not be successfully employed now, since the texts of the Bible have suffered such serious though unintended distortion.” Since liberal theologians had come to disagree with the notion of an inerrant Bible, the method of proving an argument by assembling an overwhelming dose of chapter and verse no longer seemed compelling.

During the twentieth century, however, among Bible-centered Protestants—including self-styled fundamentalists, neo-evangelicals, Pentecostal groups, conservative Lutherans, and others—the proof-text tradition continued. For those groups who maintained a faith in the Bible as inerrant, it remained convincing to prove every point with an assembly of relevant texts.

Consider the following doctrinal statement from David Cloud’s Way of Life Ministries. Each point is proven with an array of relevant texts.

STATEMENT OF FAITH

Way of Life Literature

P.O. Box 610368, Port Huron, MI 48061

866-295-4143 (toll free), fbns@wayoflife.org

http://www.wayoflife.org

THE SCRIPTURES

The Bible, with its 66 books, is the very Word of God. The Bible is verbally and plenarily inspired as originally given and it is divinely preserved in the Hebrew Masoretic Text and the Greek Received Text. The Bible is our sole authority in all matters of faith and practice. The King James Version in English is an example of an accurate translation of the preserved Hebrew and Greek texts; we believe it can be used with confidence. We reject modern textual criticism and the modern versions that this pseudo-science has produced, such as the American Standard Version, the New American Standard Version, the Revised Standard Version, and the New International Version). We also reject the dynamic equivalency method of Bible translation which results in a careless version that only contains the general ideas rather than the very words of God. Examples of dynamic equivalency versions are the Today’s English Version, the Living Bible, and The Message.

2 Samuel 23:2; Psalm 12:6-7; Proverbs 30:5-6; Matthew 5:18; 24:35; John 17:17; Acts 1:16; 3:21; 1 Corinthians 2:7-16; 2 Timothy 3:15- 17; 2 Peter 1:19-21; Revelation 22:18-19

THE CREATION

We believe in the Genesis account of Creation and that it is to be accepted literally and not figuratively; that the world was made in six 24-hour days; that man was created directly in God’s own image and did not evolve from any lower form of life; that all animal and vegetable life was made directly and made subject to God’s law that they bring forth only “after their kind.”

Genesis 1; Nehemiah 9:6; Job 38:4-41; Ps. 104:24-30; Jn. 1:1-3; Acts 14:15; 17:24-26; Rom. 1:18-21; Col. 1:15-17; Hebrews 1:1-3; 11:3

THE WAY OF SALVATION (THE GOSPEL)

Salvation is by the grace of God alone, which means that it is a free gift that is neither merited nor secured in whole or in part by any virtue or work of man or by any religious duty or sacrament. The gift of God’s grace was purchased by Jesus Christ alone, by His blood and death on Calvary. The sinner receives God’s salvation by repentance toward God and faith in the Lord Jesus Christ. Though salvation is by God’s grace alone through faith, it results in a changed life; salvation is not by works but it is unto works. The faith for salvation comes by hearing God’s Word. Men must hear the gospel in order to be saved. The Gospel is defined in 1 Corinthians 15:1-4.

John 1:11-13; 3:16-18, 36; 5:24; 14:6; Acts 4:12; 15:11; 20:21; Romans 10:9-10,13, 17; Ephesians 1:7; 1:12-14; 2:8-10; Titus 3:3-8; Hebrews 1:3; 1 Peter 1:18-19; 1 John 4:10

CIVIL GOVERNMENT AND RELIGIOUS LIBERTY

We believe that civil government is of divine appointment for the interests and good order of human society; that magistrates are to be prayed for (1 Tim. 2:1-4), conscientiously honored and obeyed (Mat. 22:21; Rom. 13:1-7; Titus 3:1; 1 Pet. 2:13-14), except only in the things opposed to the will of God (Acts 4:18-20; 5:29); that church and state should be separate, as we see in Scripture; the state owing the church protection and full freedom, no ecclesiastical group or denomination being preferred above another. A free church in a free state is the Christian ideal.

We can see the proof-text tradition in David Cloud’s sermons as well.

The way Cloud and Way of Life use proof-texts is just one example from a galaxy of possible examples out there. Especially among Bible-based conservative evangelical Protestant groups, the proof-text is the method by which truth is established. The Bible is the inerrant authority. In order to make any point, about any subject, the name of the game is proof-texting. Of course, among many conservative Protestants, the term “proof-text” has taken on negative connotations. It should not mean that one simply has to slap a bunch of Bible citations together to prove a point. In this continuing intellectual tradition, the cogency of the argument is based on the proper selection of texts. How well do the selected texts establish the point at hand? Does the author use each text in a way that respects the context and original meaning of the selected passage? Does the author consider relevant passages that might disagree with this interpretation? Or does a poorly educated pastor merely assume an air of false erudition by throwing Scriptural citations around willy-nilly?

To be sure, it is an intellectual tradition that no longer carries weight in mainstream religion and culture. Though large majorities of Americans might believe that the Bible contains the answers to all of life’s questions, those same majorities do not necessarily agree that the Bible should be the main intellectual authority in all matters. Indeed, especially galling to many non- and anti-fundamentalists is proof-texters’ assumption that their particular religious tradition should be considered binding in matters of public policy. In other words, it may be fine for Way of Life to demonstrate the validity of its creed through proof-texts. But that does not mean that proof-texts can be used to demonstrate the need to teach religious doctrine in science classes.

These are important arguments. Proof-texters need to understand that their intellectual tradition does not carry weight outside the borders of Fundamentalist America. But that is a much different thing than admitting to being non-intellectual or anti-intellectual. If we outsiders can better understand the tradition of proof-texting, we will be better able to speak intelligently, reasonably, calmly, and even productively with Fundamentalist America.

FURTHER READING: William Newton Clarke, The Use of the Scriptures in Theology (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1907); Timothy P. Weber, “The Two-Edged Sword: The Fundamentalist Use of the Bible,” Nathan O. Hatch and Mark A. Noll, eds., The Bible in America: Essays in Cultural History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), 101-120.