It has all the elements of a Left Behind novel: Government thugs storm into a Bible meeting. They threaten to arrest the pastor and fine his congregants for praying together. They appeal for community support by accusing Bible-believing Christians of “fanaticism” and “intolerance.”

And that’s the way the story is being told in some of Fundamentalist America’s news outlets, such as Glenn Beck’s Blaze. It is the tale told by the Bible pastor himself and his wife in recent YouTube videos.

Of course, neighbors and city officials in Phoenix tell a different story.

In any event, this story is worth the attention of all of us who are struggling to understand Fundamentalist America.

In short, as Ray Stern and Sarah Fenske have been following the story in the Phoenix New Times, Michael Salman is battling his neighbors over his desire to build a church in his backyard. Several years ago, he built a shed-like structure and began hosting smallish worship services there. He has been in a battle with the city ever since about code violations and his right to freedom of worship and freedom of assembly.

As Alan Weinstein, the director of the Law & Public Policy Program at the Cleveland-Marshall College of Law in Cleveland, commented in 2008,

As Alan Weinstein, the director of the Law & Public Policy Program at the Cleveland-Marshall College of Law in Cleveland, commented in 2008,

“Say I just bought a 63-inch TV, and every Sunday at 11 a.m., I have 20 people over my house to worship at the church of the NFL,” Weinstein says. “There are probably football fans who do that every Sunday. And if they don’t stop that, they can’t stop a Bible study that’s meeting once a week, either.”

The city has insisted all along that the issue is not about religion but about building and fire codes. The neighbors, too, complain about Salman’s building plans. They say his proposed church would be too close to a property line. They say it would change the character of the quiet neighborhood of large homes and large lots. But they also agree that Salman’s kind of religious zealotry left a bad taste in their mouths. As Sarah Fenske reported in 2008,

When, at a neighborhood association meeting, one neighbor told Salman he didn’t like the plan, Andrea and Mike Julius watched Salman grow visibly angry. . . .

“It was clear at that point what we were dealing with,” Andrea Julius says. “I don’t want to say someone who seemed possessed, but not a cool-headed person.”

Tom Woods remembers thinking the same thing. When neighbors complained about how his project would affect their property values, Woods says, Salman was dismissive.

“He gave us a lecture on the fact that all of us were going to make money on our property, and if we were true Christians, we ought to be willing to sacrifice a little bit,” Woods recalls. “You can imagine, a few guys in the audience were all over him for that.

“That meeting is where the real animosity started. He made no effort at being conciliatory or cooperative. That really united the neighbors against him,” Woods says. “He was his own worst enemy.”

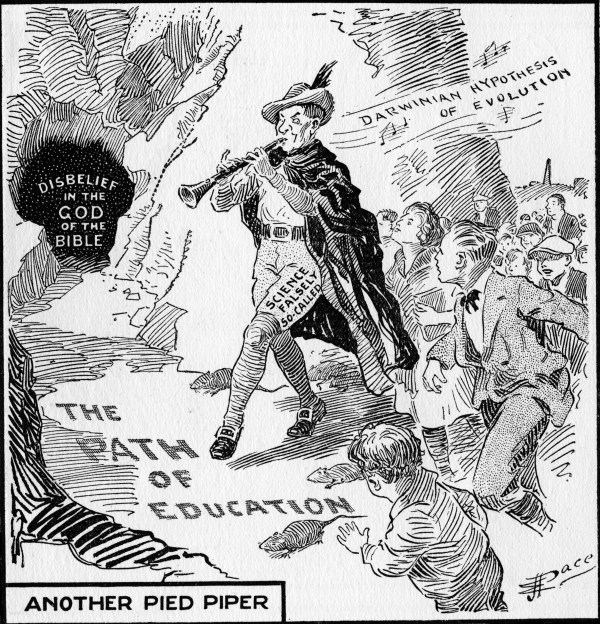

And Salman’s personal story and theology are somewhat different from what his neighbors might have hoped for. In his youth, he was a drug-using, gun-toting member of a Phoenix street gang. He served jail time for shooting up a rival’s house, nearly killing the rival’s mother. In jail, he experienced a religious conversion. Upon release, he dedicated his life to his new Bible ministry. He embraced some beliefs decidedly outside the mainstream, such as the human-government-defying Embassy of God movement. He also posted a series of sermons on YouTube, including this one in which Salman calls evolution “nothing but hogwash.”

But does that mean he shouldn’t be allowed to have a church in his backyard? He doesn’t think so.

Does the fact that he wants to build a church mean that he can ignore building codes? The city of Phoenix and his neighbors don’t think so.

Perhaps the most telling twist in this continuing story is that when Salman recently tried to turn himself in for some jail time, Phoenix authorities refused to arrest him. As Ray Stern reported in the Phoenix New Times, when Salman reported to jail to serve a pending 60-day sentence, jail officials turned him away.

Salman had an easy explanation: “God granted me an injunction.” Though Phoenix officials wouldn’t comment, the fear of bad publicity likely had more influence on their decision than the fear of God.