After Ben Carson’s stupid and hateful comment that the USA should not have a Muslim president, Baylor theologian Roger Olson noted that we really could not have a Christian president, either. In my current work about evangelical colleges, I’m struggling to define what it meant to be Christian at school, too. It raises an ancient question: Can an other-worldly religion (successfully) run worldly institutions?

Olson noted that the only sincere evangelical to sit in the Oval Office in recent decades has been Jimmy Carter. And Carter, Olson argued, was a terrible president. Not by accident, either, but because he was an honest-to-goodness Christian. As Olson put it,

I am not cynical, but neither am I naïve. America is no longer a true democracy; it is run by corporations and the super-rich elite. Occasionally they don’t get their way, but, for the most part, they do. One reason they do not seem to is that they do not agree among themselves about everything. So, sometimes, a president, a senator, a congressman, has to choose between them in decision-making. But, in the end, the policy remains that “What’s good for business is good for America” even when what’s good for business is bad for the working poor (to say nothing of the destitute).

No, given how modern nation states work, I do not think a real Christian, a true disciple of Jesus Christ who seeks to put first the kingdom of God and God’s righteousness, can be president of the United States or any modern nation state.

The deeper question of belief and institutional necessity is one I’m wrestling with these days. As I write my new book about the history of evangelical higher education, I find myself struggling to offer a satisfactory definition of what it has meant to be a fundamentalist. It’s a question that has bedeviled historians (and fundamentalists) for a good long while, so I feel I’m in good company.

For good reasons, historians have insisted that we need a fairly narrow definition of fundamentalism. In his great book Revive Us Again, Joel Carpenter argued, “more generic usage obscures more than it illumines” (page 4). Carpenter was leery of commentators who slapped a “fundamentalist” label on any and all conservatives or conservative Protestants. As he argued,

Labelling movements, sects, and traditions such as the Pentecostals, Mennonites, Seventh-day Adventists, Missouri Synod Lutherans, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Churches of Christ, black Baptists, Mormons, Southern Baptists, and holiness Wesleyans as fundamentalists belittles their great diversity and violates their unique identities (4).

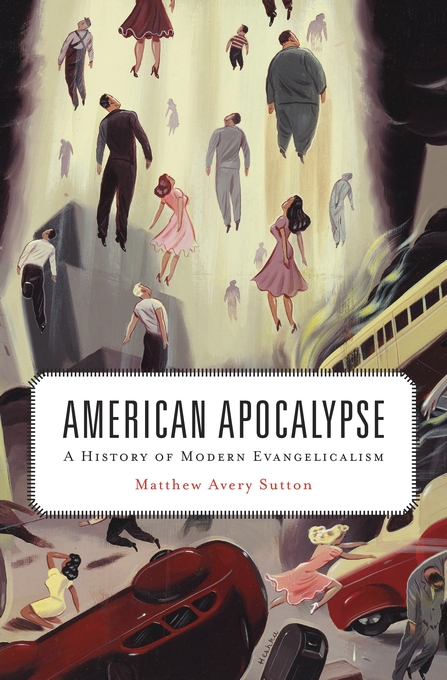

If we need a straightforward definition for those reasons, Matthew Sutton’s recent definition of fundamentalism as “radical apocalyptic evangelicalism” will do the trick. Certainly, fundamentalist theology was defined by its vision of end-times as well as by the centrality of those apocalyptic visions to the movement.

But such definitions don’t seem to match the ways fundamentalism has been defined in its leading institutions. At the colleges I’m studying—schools such as Wheaton College, Bob Jones University, Bryan College, Biola University, The King’s College, and similar schools—there’s more to the school than just theology.

When these schools called themselves “fundamentalist” (and they DID, even relatively liberal schools such as Wheaton), they meant more than theology. They meant more than just “radical apocalyptic evangelicalism.” They meant more than just “not-Mennonite-or-Pentecostal.”

Defining fundamentalism as it was used in fundamentalist institutions is a trickier issue than simply defining fundamentalist theology. By and large, when schools talked about themselves as “fundamentalist,” they meant that the professors and administration all signed on to fundamentalist theology. But they also meant that the students would have a vaguely conservative atmosphere in which to study. No smoking, no dancing, no etc. They also meant that students would be controlled and guided in their life choices. And they also meant that students would be more likely to socialize with similarly fundamentalist friends and future spouses.

I’m not sure how to define that kind of fundamentalism. I like the way historian Timothy Gloege has done it in his new book about the Moody Bible Institute. Gloege focuses on what he calls the “corporate evangelical framework” that guided MBI since its founding in the 19th century.

As Gloege argues, at a school like MBI, fundamentalism was more than a set of “manifestos and theological propositions.” Rather, it worked as a set of “unexamined first principles—as common sense.” Fundamentalism, Gloege writes, is better understood as a certain “grammar” than as a list of religious beliefs.

That kind of definition seems closer to the ways it was used in the schools I’m studying.

Roger E. Olson argues that it will be impossible for any sincere evangelical Christian to be president. There are simply too many worldly factors that violate the otherworldly morality of Christianity. Similarly, evangelical colleges have not defined themselves merely along theological lines. They couldn’t. Instead, they have defined what it has meant to be a “fundamentalist” based on a range of factors. Of course, they care about student religious belief. But they also care about student fashions, patriotism, diets, and social lives. And such things were usually considered a central part of making a school authentically “fundamentalist.”

Can a college be Christian? In the sense that Roger E. Olson is asking, I guess not. Just as every president has to violate evangelical morality, so every institution of higher education has to consider a range of non-religious factors in order to survive.