Anti-creationists have warned about it for generations: Creationists are joining forces to sweep away reason and science. A growing conspiracy of dunces threatens to upend centuries of progress. But a recent tiff between leading American creationists demonstrates just how fractured and divided creationists really are. And it demonstrates the ways hysterical anti-creationism may do more harm than good.

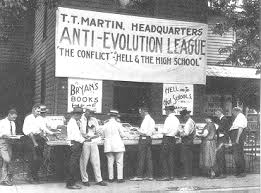

The threats of a creationist conspiracy go back to the roots of America’s evolution/creation culture wars. In his 1927 book, The War on Modern Science, Maynard Shipley warned that the fundamentalist “forces of obscurantism” threatened to overthrow real learning. As Shipley put it,

The armies of ignorance are being organized, literally by the millions, for a combined political assault on modern science.

Ever since, science writers have warned of this impending threat. Isaac Asimov, for instance, warned in 1981 of the “threat of creationism.” Such unified anti-scientists, Asimov believed, had made great strides toward setting up “the full groundwork . . . for legally enforced ignorance and totalitarian thought control.” Like Shipley, Asimov noted that not all religious people are creationists, but also like Shipley, Asimov failed to notice the differences between creationists. The only religious people one could trust, Asimov wrote, were those “who think of the Bible as a source of spiritual truth and accept much of it as symbolically rather than literally true.”

What Asimov missed was the crucial fact that many creationists DO endorse real science; many folks who think of the Bible as more than just symbolic also accept the ideas of an ancient earth and human evolution.

This is more than just a quibble. When leading scientists and science pundits lump together all creationists as “armies of ignorance,” they needlessly abandon and heedlessly insult potential allies in creation/evolution debates. When science writers such as Jerry Coyne attack all religious discussion as “accommodationism,” they unnecessarily alienate creationists who want to teach more and better evolution.

A recent interchange between leading creationists demonstrates the way international creationism really works. Creationism in practice is not a horde of Bible-believing fanatics, relentlessly unified on the age of the earth and the origins of humanity. In practice, rather, creationism is a splintered and fractious impulse, fighting internal foes more viciously than external ones.

The “evolutionary creationist” Deborah Haarsma, leader of BioLogos, recently reached out to young-earth creationist leader Ken Ham of Answers In Genesis. Haarsma was “troubled” by Ham’s angry polemic about a third creationist, Hugh Ross of the old-earth Reasons to Believe.

We all have our differences, Dr. Haarsma said. But why can’t we come together over our shared Biblical faith? About our shared concern that young people are leaving the church? Why can’t we at least sit down together for a cordial dinner and talk over our differences?

Ken Ham publicly rebuffed Haarsma’s efforts. Ham agreed that his animus toward Ross was not at all personal. As Ham explained, “I don’t consider Dr. Ross a personal enemy . . . he is actually a pleasant person.” But Ross was also an “enemy of biblical authority.” And Haarsma was no better. “People like Dr. Haarsma,” Ham wrote,

make it sound like they have such a high view of the Bible, whereas in reality, she has a low view of Scripture and a high view of man’s fallible beliefs about origins!

There will be no dinner. There will be no grand alliance of creationists. Instead, we see the ways some creationists will tend to isolate themselves into smaller and smaller like-minded communities.

This story spreads beyond the borders of the United States. As historian Ronald Numbers described in The Creationists, in the mid-1980s the minister of education in Turkey wrote to the San-Diego based Institute for Creation Research. Turkey’s schools, the minister wrote, needed to “eliminate the secular-based, evolution-only teaching dominant in their schools and replace it with a curriculum teaching the two models, evolution and creation, fairly” (pg. 421). And Islamic creationism, much of it based in Turkey, has thrived. However, Numbers concluded, “the partnership between the equally uncompromising Christian and Muslim fundamentalists remained understandably unstable” (425). Numbers cited the rhetoric of American creationist leader Henry Morris: “Mohammed is dead and Jesus is alive!” As Numbers noted acerbically, such talk was “hardly calculated to win Muslim friends” (425).

There will be predictable tensions between different types of creationists. Though some conservative religious voices will work to spread evolutionary theory among evangelicals, others will focus on what Ken Ham called “rebuilding a wall” (Nehemiah 6:1-3).

Folks like me who want to see more and better evolution education will be wise to reach out to those conservative religious folks who also believe in evolution. Instead of copying the tactics of Ken Ham, as Jerry Coyne is prone to do, science promoters should embrace allies and make friends. Instead of shrieking about the “armies of ignorance,” science promoters will do well to look closer at the creationist population. There are plenty of friends there.