–Knock knock.

–Who’s there?

–A smaller government, a vigorous military presence abroad, and traditional values.

Get it? According to Frank Rich, no one does. Conservatism just isn’t funny. In a terrific essay last week in New York Magazine, Rich explores the tortured relationship between conservatism and comedy.

Rich wonders why there are no big conservative comedians out there, no flipside to the Jon Stewarts and Stephen Colberts. He mentions a couple of contenders, such as Dennis Miller and even South Park. But they are either not very funny or not very conservative. And, as Rich points out, it seems like there would be plenty of funding for a vigorous conservative comedy effort. But the few that have been made, such as the lamentable ½ Hour News Hour, are only embarrassing for us all.

Rich doesn’t make the case, but it seems as if conservatism, as a rule, should have the upper hand when it comes to laffs. After all, as Hannah Arendt argued long ago, conservatives in general have the easier job in cultural polemics. They can joke about each new innovation. They can skewer new trends and rely on long-standing traditions to pillory liberal excesses.

But, as Rich points out, they don’t. Why not? Why aren’t conservatives funny?

Rich argues that too many conservative comedians are conservatives first and comedians second. After all, “liberal” jokesters such as Jon Stewart don’t hesitate to joke about liberal heroes. Stewart puts the jokes first and the politics second.

When liberals forget this simple rule, they are just as unfunny as conservatives. Remember Leslie Knope’s (Amy Poehler’s) stilted attempt at sex-education humor? It just wasn’t funny.

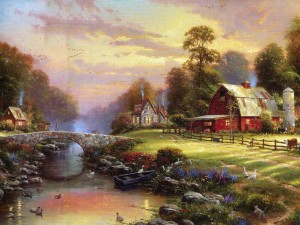

This rule applies outside of comedy, of course. Some conservative intellectuals embrace the paintings of the late Andrew Wyeth, for example, as “conservative” masterpieces. Consider the vast difference, though, between Wyeth’s brand of painting and the conservatism-on-his-sleeve style of Jon McNaughton.

As Rich notes about comedy, art of any sort seems to suffer when pundits put ideology first and art second.