How did American public schools get started? Like the rest of us, conservative intellectuals and activists have always told themselves stories that confirmed what they wanted to believe. This morning, we see another expression of century-old conservative myths about educational history.

As I found in the research for my book about educational conservatism, conservatism has always been fueled by a false notion of America’s past. When it comes to schools and schooling, conservative activists since at least the 1930s have told themselves that schools used to be great, but scheming progressive New Yorkers took over at some point and ruined everything.

Schools USED to be great…

Consider this example from my favorite twentieth-century educational conservative, Max Rafferty. Rafferty was the superintendent of California’s public schools in the 1960s. He was a popular syndicated columnist and almost won the US Senate race in 1968. One of the reasons for Rafferty’s popularity was his persuasive but false vision of educational history. He told readers over and over again that American public schools used to be great, local institutions. The problem came, Rafferty explained, when New York “progressives” took over.

As Rafferty wrote in his 1964 book What They Are Doing to Your Children,

Wherever progressive education was allowed in infiltrate—and this was almost everywhere—the mastery of basic skills began insensibly to erode, knowledge of the great cultures and contributions of past civilizations started to slip and slide, reverence for the heroes of our nation’s past faded and withered under the burning glare of pragmatism.

This morning we stumbled across a 2018 update of this twentieth-century just-so story. Writing from Pepperdine’s American Project, Bruce Frohnen tries to explain why conservatives hate public schools. Along the way, Prof. Frohnen makes big false assumptions about the history of those schools.

First example: Like a lot of conservatives, Frohnen incorrectly assumes that federal and state leaders call the shots in public schools. As Prof. Frohnen puts it,

The problem is precisely that they are run by people and according to rules that are too distant from, and consequently hostile toward, our local communities.

Not really. Most teachers ARE the local communities. As Stanford’s Susanna Loeb found,

A full 61 percent of teachers first teach in schools located within 15 miles of their hometown; 85 percent get their first teaching job within 40 miles of their hometown. And 34 percent of new teachers took their first job in the same school district in which they attended high school.

Similarly, Penn State political scientists Michael Berkman and Eric Plutzer found that the most important factor driving teachers’ choices about evolution education was local values. If communities wanted evolution taught, teachers taught it. If they didn’t, they didn’t.

If schools aren’t local, why are so many locals happy with them?

So, yes, the impact of federal funding has increased since 1950. But most of the day-to-day decisions about schooling and education are made at the very local level. This localism might explain why most American parents are actually very happy with their children’s schools. Gallup polls have consistently found that most people grade their kids’ schools highly, in spite of the hand-wringing by pundits like Dr. Frohnen.

Second example: Like a lot of people, Prof. Frohnen mischaracterizes the early history of American public education. As he argues [emphasis added by me],

Today, politicians, professional educators, and administrators all tell us that the federally-regulated public school is essential to American public life—that it is the place where children from widely divergent socio-economic, racial, and ethnic backgrounds come together to learn what it means to be an American. It is understandable that Conservatives harken back to this vision as they face an education establishment determined to undermine our common culture. But we need to remember that historically American schools integrated students, not into some national community defined by ideology, but into local communities defined by tradition, history, and local relationships. Nationalized education got its start with the famous 19th century educator, Horace Mann.

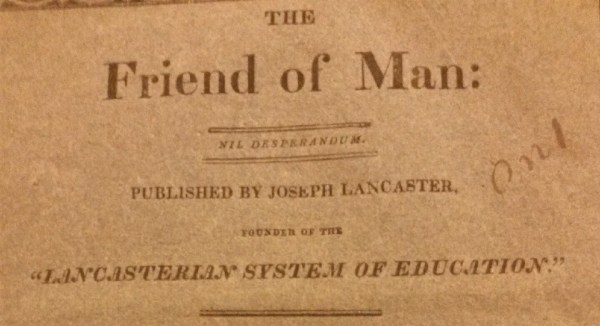

Nope. From the get-go, ed reformers promised that publicly funded schools would serve a national purpose. And those reformers preceded the attention-hogging Horace Mann. Consider just a couple of examples from my recent research into the career of Joseph Lancaster. Starting in 1818, Lancaster swept into Philadelphia, New York, and other cities, promising that his “system” could educate a new nation’s children.

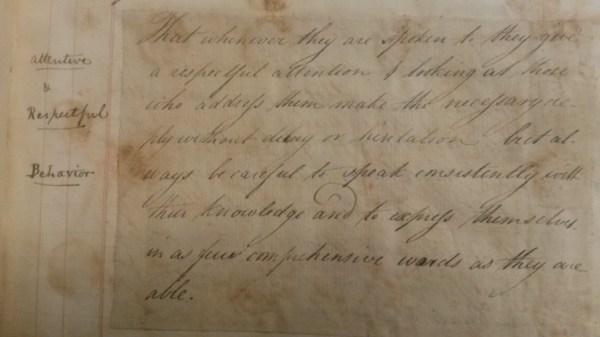

Lancaster and his fellow reformers insisted that their goal was precisely to train NATIONAL citizens, not local ones. As he wrote in a 1817 guide to his system [emphasis added again],

Another inducement to pursue the Lancasterian system, as it respects the state at large, is the uniformity of principles and habits, which would be thus inculcated among the children of those citizens who are the subjects of this kind of instruction, a desideratum essential to the formation of correct national feeling and character.

In all of his early writing, Lancaster explicitly promoted his scheme as a way to foster “NATIONAL EDUCATION” [his emphasis this time]. Indeed, one of the reasons Lancaster’s reform plan was so popular in the 1810s was precisely because it promised to train national citizens—at the time, the security of the new nation was extremely shaky.

So, SAGLRROILYBYGTH, agree with Prof. Frohnen’s ideas about public schools or don’t. Embrace his vision of conservative principles or don’t. But whatever you do, don’t listen to pundits who tell you that America’s public schools are ruled by any distant power. And don’t buy the old line that schools in the old days used to be about purely local values.

It just ain’t so.

Soon, the young Lancaster started believing his own fundraising spiel. He promised the leaders of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia that his master plan could work in any school, anywhere. It couldn’t and it didn’t. The mistake Lancaster made—one of them, at least—was to assume that his limited successes were due to the specific methods he was using, rather than to his endlessly deep royal pockets and his authentic love and enthusiasm for his school and students.

Soon, the young Lancaster started believing his own fundraising spiel. He promised the leaders of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia that his master plan could work in any school, anywhere. It couldn’t and it didn’t. The mistake Lancaster made—one of them, at least—was to assume that his limited successes were due to the specific methods he was using, rather than to his endlessly deep royal pockets and his authentic love and enthusiasm for his school and students.