It doesn’t look good.

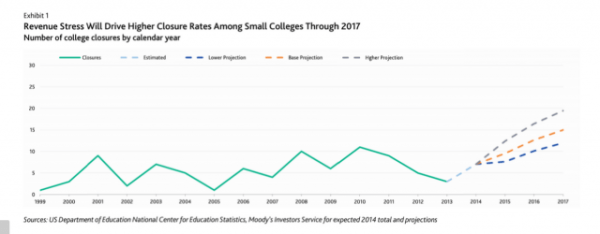

For small colleges of any sort, the future looks grim. A new report from Moody’s (the investor service, not the Bible institute) offers some scary predictions about the iffy future of small schools. For conservative evangelical colleges, however, this looming financial crisis also represents a uniquely religious crisis. Will small evangelical colleges be able to resist the growing pressure to become more radical in their orthodoxy?

Inside Higher Education describes the sobering financial outlook. In the next few years, college closings will likely triple. Why? Fewer students means fewer tuition dollars, which means fewer scholarship dollars, which means fewer students. Rinse and repeat.

Among conservative evangelical schools, we’ve already seen the trend. Former evangelical schools such as Northland University, Tennessee Temple, and Clearwater Christian have all closed their doors. In some cases, the “Wal-Marts” of Christian colleges have emerged even stronger. Cedarville University, for example, has offered to accept all students from Clearwater Christian. As with non-evangelical schools, the big will likely get bigger and the small will get gone.

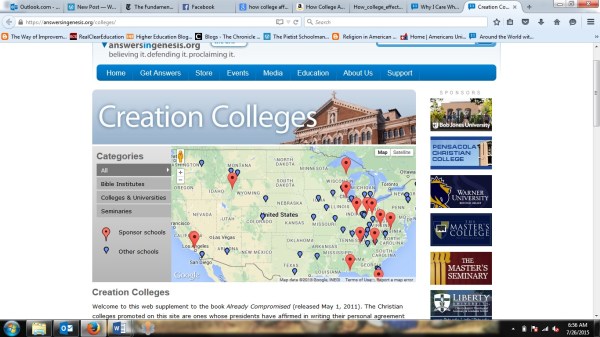

For small evangelical colleges, this presents a double pickle. In desperate need of more students, schools will likely become extra-timid about offending conservative parents and pundits. As I’ve argued before, young-earth impresarios such as Ken Ham already exert outsize influence on college curricula. If Ham publicly denounces a college—which he likes to do—you can bet young-earth creationist parents might listen.

We’ve seen it happen at Bryan College. Rumors of evolution-friendly professors caused administrators to crack down. Any whiff of evolutionary heterodoxy, and schools might scare away potential creationist students.

At other evangelical colleges, too, as we’ve already seen in schools such as Mid-America Nazarene or Northwest Nazarene, administrators desperate for tuition dollars will be tempted to insist on a more rigidly orthodox reputation.

Things aren’t looking good for small colleges in general. But conservative evangelical schools face this special burden. In order to attract the largest possible number of students in their niche, they might have to emphasize more firmly the things that make them stand out from public schools. In the case of conservative evangelical schools, that distinctive element has always been orthodoxy.

In the past, well-known schools such as Bryan College might have relied on their long history as staunchly conservative institutions. They might have assumed that conservative evangelical parents would trust their orthodoxy, based on their long-held reputation as a bastion of conservative evangelical education. These days, no-holds-barred competition for students will mean that every school must guard its image far more aggressively.