We should be freaking out. It’s not just that Americans don’t know about basic democratic principles. In increasing numbers, we don’t seem to care. Pundits lately have hoped we might be in a rock-bottom crisis of civics education, a “Sputnik moment” that drives Americans to re-invest in basic education in democratic ideas. We’re not. Our civics stand-off is even more hopelessly rancorous than our never-ending fights about creation and evolution.

Last year, Richard D. Kahlenberg and Clifford Janey hoped that the ugly, bizarre emanations from Trump’s White House might scare America straight when it came to civics education. It wasn’t only Trumpism that alarmed them. The numbers seemed truly shocking and getting worse. As they explained,

Civics literacy levels are dismal. In a recent survey, more than two-thirds of Americans could not name all three branches of the federal government. . . . Far worse, declining proportions say that free elections are important in a democratic society.

When asked in the World Values Survey in 2011 whether democracy is a good or bad way to run a country, about 17 percent said bad or very bad, up from about 9 percent in the mid-1990s. Among those ages 16 to 24, about a quarter said democracy was bad or very bad, an increase from about 16 percent from a decade and a half earlier. Some 26 percent of millennials said it is “unimportant” that in a democracy people should “choose their leaders in free elections.” Among U.S. citizens of all ages, the proportion who said it would be “fairly good” or “very good” for the “army to rule,” has risen from one in 16 in 1995, to one in six today. Likewise, a June 2016 survey by the Public Religion Research Institute and the Brookings Institution found that a majority of Americans showed authoritarian (as opposed to autonomous) leanings. Moreover, fully 49 percent of Americans agreed that “because things have gotten so far off track in this country, we need a leader who is willing to break some rules if that’s what it takes to set things right.”

More recently, Robert Pondiscio and Andrew Tripodo offered a few specific suggestions about how teachers can “seiz[e] the moment to improve civics education.”

I share their concern and Pondiscio and Tripodo offer some smart concrete steps to start making improvements. As all these authors are surely aware, though, civics education faces an impossible challenge.

Consider the Sputnik analogy: Back in 1957, Americans were rightly dismayed that the Soviet Union had taken the lead in space technology. Among the many results was a new burst of funding for new science textbooks, books that no longer truckled to the political power of creationists. The BSCS series included robust information about evolution, and by the end of the 1960s those books were being widely used in American classrooms. (If you’re looking for a quick guide to this history, check out Teaching Evolution in a Creation Nation.)

We aren’t facing a similar situation when it comes to our shoddy civics education.

Why not? Much as creationists might not like it, by 1957 the mainstream scientific community had reached a powerful consensus about the basic outline and importance of the neo-Darwinian synthesis. There is no similar mainstream establishment that can satisfactorily define the proper aims of civics education.

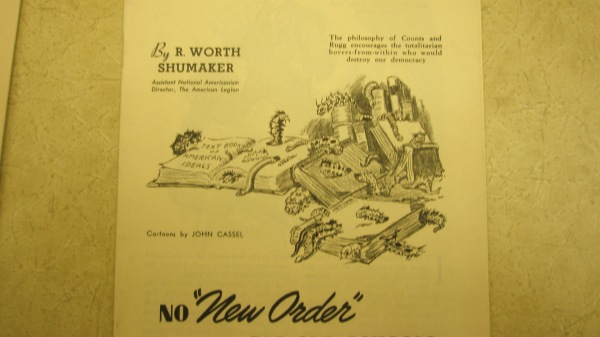

Consider the example I included in my book about educational conservatism. Back in the late 1930s, a set of widely used social-studies textbooks became intensely controversial. Harold Rugg’s books had been used by millions of students, but in just a few short years they were mostly all yanked from classroom use.

Watch out: Your school might be teaching civics…

The problem was that Rugg was pushing his vision of civics education. It was a vision that conservatives such as the founder of Forbes Magazine and leaders of the American Legion found subversive.

What did it mean in the World War II years to educate citizens? Harold Rugg thought it meant teaching them the dangers of authoritarianism. He thought it meant teaching them that the United States was one country among many, and that citizens needed to be rigorously skeptical of big business and back-room government deals.

Conservatives thought it meant teaching students to honor and cherish the best American traditions. They wanted children in school to learn to be proud Americans, not weak-kneed socialists. Bertie Forbes explained his beef in one of his popular syndicated columns. He was chatting one day with a group of middle-school students, Forbes related, and they told him about their experience with their Rugg books. When their teacher asked them if the United States was the best country in the world, many of them had answered “Yes.” The correct answer, their teacher read from their Rugg teachers guide, was “No.” In his column, Forbes teed off on that sort of civics education:

Do American parents want their children taught such ideas? Do they want them to be inculcated with the idea that the United States is a second-rate country, that its form of government is open to question, that there are other countries more happily circumstanced and governed than ours?

Maybe I’m getting too cynical in my old age, but I don’t think we have evolved very far from this 1940s level. When it comes to civics education, we face a stark and glaring divide about the fundamental purposes of such a class. Are students getting a good civics education if they learn how to properly, reverently, fold a flag? Are they getting a good civics education if they can rattle off the correct structure of federal government? Or are they getting a good civics education when they learn how to stage a Black Lives Matter protest?

We can’t agree. And until we can, we will continue to have shameful outcomes in our attempts to teach civics in public schools.