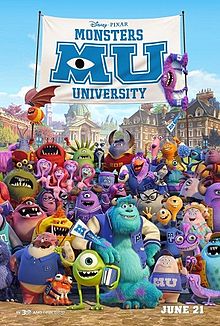

Does Monsters University have a conservative anti-MOOC message?

I took my daughter to see it the other day. It was great. I laughed. I cried. There were lots of creatively imagined monsters, smart dialogue, and sight gags. Plus a heartwarming story of friendship and dedication.

But was it also a Disney-fied version of conservative arguments about the fate and future of higher education?

But was it also a Disney-fied version of conservative arguments about the fate and future of higher education?

I couldn’t help wondering what the conservative intelligentsia would have to say about the movie’s implications for the future of higher education. Especially about the latest craze to sweep the educational establishment, Massive Open Online Courses.

Conservatives have been divided about the moral and practical implications of MOOCs.

Some free-market aficionados have trumpeted the promise of the new approach. By providing courses for free from elite universities such as Harvard and MIT, MOOCs make world-class learning more widely available than ever. Economist Richard Vedder, for example, argued that a MOOC approach could cull out inefficiencies in higher education.

More recently, Benjamin Ginsberg fretted that MOOCs represented just another way for administrators to cut apparent costs, at the real cost of abolishing real learning.

Other conservatives have agreed that the MOOC model abandons the proper goal of higher education. Rachelle DeJong complained that higher ed must take more responsibility for the formation of young minds and spirits. “The student,” DeJong wrote,

as yet unformed and uneducated, cannot judge what studies best suit his needs, his vocation, or his intellectual development. How can he discern a steep ascent to the mountaintop from a difficult dead-end, when all he knows are the briars, the rocks, and the stitch in his side?

In the pages of Minding the Campus, Peter Sacks warned that MOOCs will generate a crushing mediocrity and exacerbate the existing class divide among institutions of higher education. Rich students will get a full learning experience, Sacks insisted, while less well-off students will only hear distant digital echoes of profound learning environments.

Such conservative arguments make sense to the historian in me. Even a nodding acquaintance with the history of technology and education makes anyone skeptical of any new technological “revolution” for classrooms. As Larry Cuban has demonstrated, new technologies often garner enthusiasm and enormous investment, only to crash against the reefs of complex educational reality.

Perhaps the best example was the flying broadcast technology of the 1950s. The US government and the Ford Foundation poured tens of millions of dollars into this program, which sent planes circling over the Midwest and Great Plains. These planes broadcast educational television programs to schools in those areas. The idea was that the very best teachers could supply content for audiences of schoolchildren nationwide.

The program failed because schooling is about much more than simply receiving information from a TV screen. CAN young people learn this way? Of course. Is such learning the equivalent of all the complex interactions that go into our notion of “school?” Of course not.

A similar future seems in store for MOOCs. Such distance learning is nothing really new and some students will likely benefit greatly from it. But it will not replace the entirety of higher education, since that entirety includes such a broad range of ingredients.

What does all this have to do with adorable monsters? I won’t give away any of the plot of Monsters University, but I can say that the movie centers around the dreams of a young adorable monster who yearns to attend Monster University. The film includes long sweeping vistas of colored foliage and ancient-looking buildings. It revolves around the intense traditions and intense personal interactions that make up higher education for monsters.

The main character, to be sure, went to MU for vocational reasons. He wanted to earn a certain type of job. Without giving away the plot, I can’t comment here on some of the movie’s ultimate implication about the career efficacy of those choices.

But for the main monster character, the allure of MU was at least as much about personal relationships between students and a hard-nosed dean as it was about attaining information. The attraction of MU depicted in the film was at least as much about learning from fellow students as it was about downloading information from star professors. The campus and its social scene played crucial roles in the education depicted in the film.

If the film gives us anything beyond two pleasant hours in an air-conditioned theater, it is an emotional, playful articulation of the drier anti-MOOC arguments made by conservative intellectuals. College, in this film, is a whole-life experience. College includes formal education, but it also requires a whole lot more. In order to be educated, the film implies, young people must submit to a stupendous tradition. Institutions of higher learning, as portrayed in this summer fantasy, are literally supernatural conglomerations of love, life, and learning.

Such conglomerations can never be replaced with online learning platforms. No matter how much star power goes into them.