If the spotlight-loving science pundit Lawrence Krauss really thinks public schools can eliminate creationism in one generation, he’s off his rocker. But he’s in good company. Through the years, all sorts of writers and activists have made grandiose plans to use public schools for one sweeping reform or another. Unfortunately for them, that’s just not how America’s schools work.

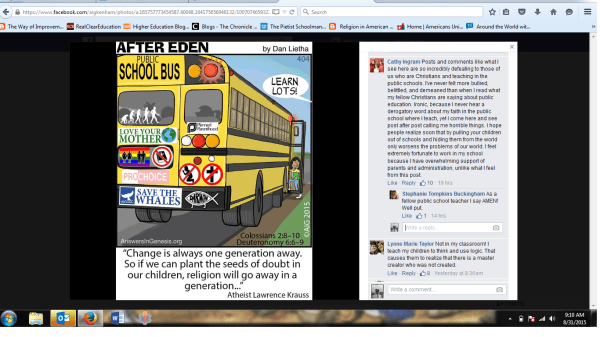

To be fair, in the Krauss quotation pirated here by the young-earth creationist ministry Answers In Genesis, Krauss does not say that this will be a school thing. He only says that we can teach our kids—in general—to be skeptical. Clearly, in the conservative creationist imagination of the folks at AIG, this teaching will take place in the public schools.

This AIG cartoon illustrates the many ideological trends that they think are taught in the public schools. Evolution, homosexuality, abortion, . . . all these ideas are poured down the throats of innocent young Christians in public schools. Furthermore, AIG thinks, Christian belief and practice are banned and ridiculed.*

In culture-war battles like this, both sides made sweeping and incorrect assumptions about public schooling. If the schools teach good science, Krauss and his allies assume, then creationism can soon be eliminated. If the schools teach good religion, AIG thinks, then children will go to heaven, protected from evolution and other skepticism-promoting notions.

As I argue in my recent book, these assumptions are hard-wired into our culture-war thinking. Both progressives and conservatives tend to assume that the proper school reform will create the proper society.

In the 1930s, for instance, at the progressive citadel of Teachers College, Columbia University, Professor George Counts electified his progressive audiences with his challenge. Public schools teachers had only to “dare,” Counts charged, and the schools could “build a new social order.”

Decades later, conservative gadflies Mel and Norma Gabler repeated these same assumptions. Conservative parents, the Gablers warned, must watch carefully the goings-on in their local public schools. “The basic issue is simple,” they wrote.

Which principles will shape the minds of our children? Those which uphold family, morality, freedom, individuality, and free enterprise; or whose which advocate atheism, evolution, secularism, and a collectivism in which an elite governs and regulates religion, parenthood, education, property, and the lifestyle of all members of society?

Professor Counts would not likely have agreed with the Gablers on much. But he would have agreed that the ideas dominating public schools matter. If the wrong ideas leach into the schools, then society will lurch in dangerous directions.

These days, both Professor Krauss and the creationists at AIG seem to have inherited these same assumptions. However, as this screenshot from AIG’s facebook feed demonstrates, public school classrooms are far more complicated places than any of our school activists have allowed. No matter what standards we write about science or religion, public schools will continue to function in ways that represent the wishes of their local community. No matter how daring they are, a few progressive teachers do not have the power to build a new social order.

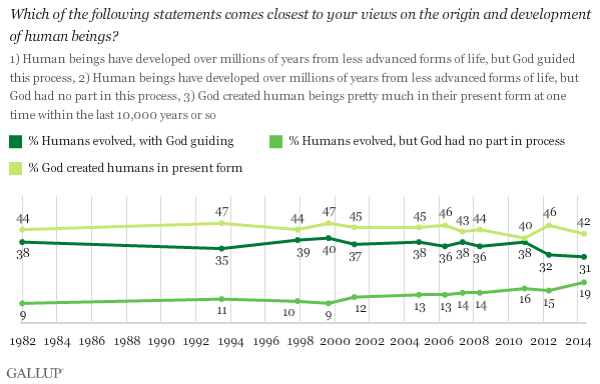

Similarly, we cannot use schools to eliminate creationism. If we want people to think scientifically, then we need to wage a much broader campaign. We need to convince parents and children that modern evolutionary science is the only game in town.

Because even if we wanted to, we could never ram through any sort of school rule that would be followed universally. Even if public schools officially adhere to state standards that embrace modern evolutionary science, schools themselves will vary from town to town, even from classroom to classroom. The only way to change schools in toto is to change society in toto.

Chicken and egg.

As we see in this facebook interchange, one evangelical teacher claims she teaches with the “overwhelming support of parents and administration.” Another says she teaches her children in public schools to recognize the logical necessity of a creator.

These facebook comments are not anomalies. According to political scientists Michael Berkman and Eric Plutzer, about 13% of public high-school biology teachers explicitly teach creationism. Another 60% teach some form of evolution mixed with intelligent design and creationism.

Why do so many teachers teach creationism? Because they believe it and their communities believe it. As Berkman and Plutzer argue, teachers tend to embrace the ideas of their local communities. In spite of the alarmism of the folks at AIG, public schools just aren’t well enough organized to push any sort of agenda. Public schools will never eliminate creationism. They just can’t.

SAGLRROILYBYGTH are sick of hearing it, but I’ll say it again: Schools don’t change society; schools reflect society.

*(Bonus points if you can explain why AIG is against saving the whales!)