What do new teachers need to know? Should they learn specific teaching methods? Or instead a more generic intellectual approach to teaching and learning? The obvious answer, it seems to me, is a little bitta both. Historically speaking, however, long and bitter experience has proven that merely training teachers to deliver a single “system” has failed miserably.

If new teachers simply learned his fool-proof system…

This old question was raised again recently in the pages of the Fordham Institute’s Flypaper blog by teachers Jasmine Lane and John Gustafson. As they warn, their teacher-ed program left them feeling abandoned. As they put it,

we were not trained in how to actually teach. Our training felt more like a philosophy of teaching degree than ensuring students could learn the tangible skills required for success in high school and beyond.

I feel for them. More than that, I remember feeling a similar way when I started—left on my own, scrambling to prepare for Monday and wondering if last Friday was helpful for my students. Even veteran teachers struggle to know what to do and too often new teachers are left feeling isolated and underprepared.

So should teacher-ed programs help new teachers know exactly what to do? I work every day with talented new teachers, so personally I share the desire to provide teachers with practical, helpful ways to deliver useful lessons and to evaluate student learning. But I’m still skeptical about a couple of things.

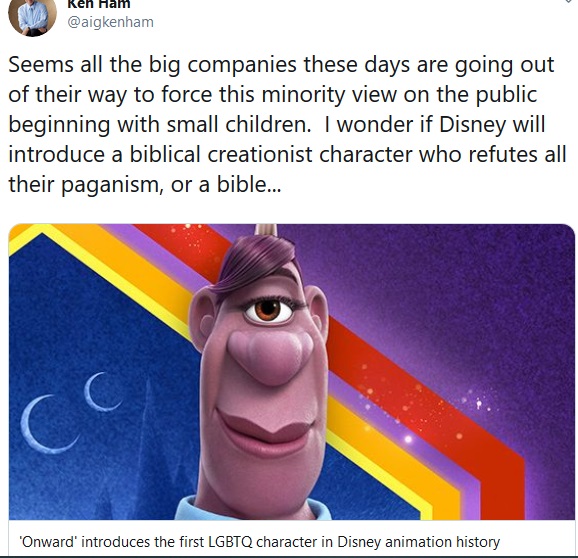

…nothing could possibly go wrong. All teachers need is the right system and the right tools…

First, as a history teacher, I know far less than Lane and Gustafson do about specific methods of reading instruction. They advocate “effective whole-group instruction or the “Big 5” components of reading.” Would that be better? I admit it happily: I don’t know.

As a historian, however, I’ve seen the dismal effect of trying to impose a one-size-fits-all teaching “system” on new teachers. As SAGLRROILYBYGTH are sick of hearing, I’m up to my eyeballs these days in research for my new book about America’s first major urban school reform.

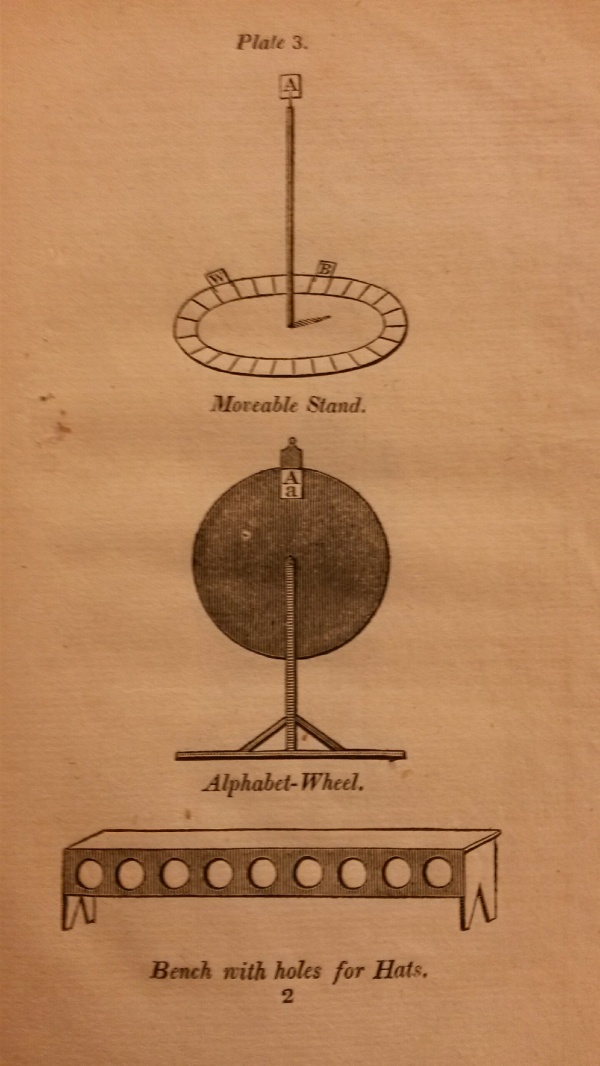

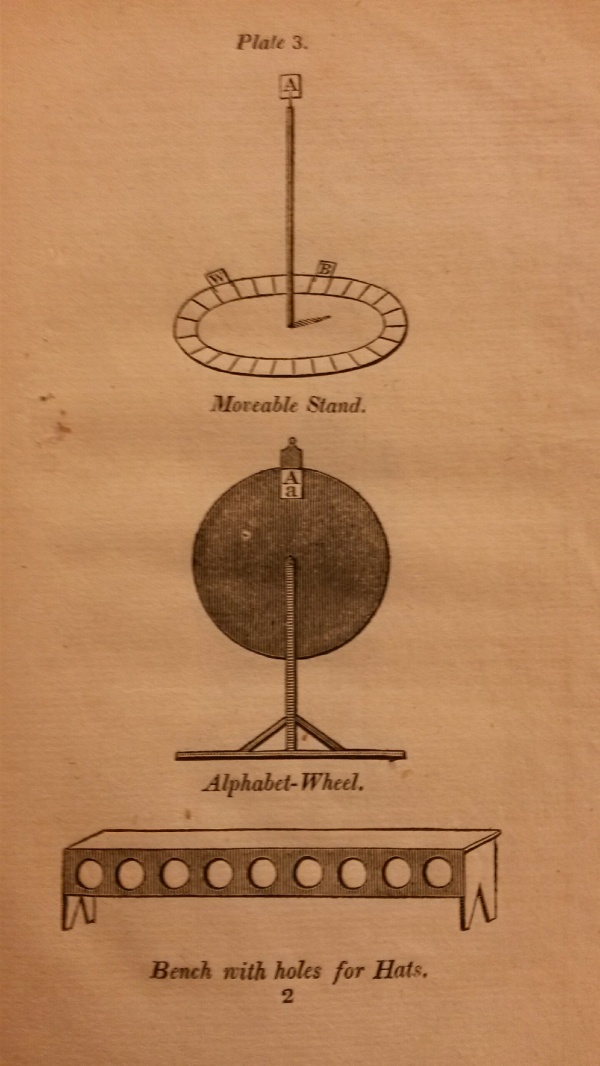

Back in the 1810s, growing cities such as Philly, New York, Baltimore, and Cincinnati wondered what they could do with all their wild American children. They turned to young London reformer Joseph Lancaster. Since (about) 1798, Lancaster had run a school for low-income London youth. More importantly, he used his school primarily as a teacher-training institute.

Lancaster promised that he had created the perfect “system.” With Lancaster’s careful instruction, anyone could teach, because Lancaster provided perfect guidance. Lancaster’s system, in short, taught teachers exactly what to do. It taught teachers, in other words, “how to actually teach.”

As Lancaster wrote in 1807,

On this plan, any boy who can read, can teach; and the inferior boys may do the work usually done by the teachers, in the common mode: for a boy who can read, can teach, ALTHOUGH HE KNOWS NOTHING ABOUT IT…

What happened? In short, it didn’t work. Among other faults with Lancaster’s system, new teachers found that their “training” did not really teach them what to do. It did not teach them “how to actually teach,” because actual teaching requires flexibility and a wealth of methodological tools, not just one system or method.

In practice, as Lancaster-trained teachers fanned out around the world, they found themselves in exactly the same predicament as Lane and Gustafson, but from the opposite direction. That is, Lancaster-trained teachers found that the simplistic system they had learned did not prepare them for the exigencies of real-world classrooms. Unlike Lane and Gustafson, they yearned for a broader education about teaching and learning, instead of only one over-hyped “system.”

When they got to their new classrooms, Lancaster-trained teachers found they had to make things up on the fly. They found that Lancaster’s pre-fabricated instructions did not address important questions of teaching and learning. In a few years, the actual teaching practices in Lancasterian schools had come to vary widely. By 1829, Lancaster felt it necessary to denounce “erroneous practices” that had taken over Lancasterian schools.

What would have been better? To this reporter, it seems obvious that a simple training program for teachers has never been enough. Because real-world classrooms are infinitely complicated places, new teachers cannot be “trained” in only one method of teaching. Instead, new teachers should learn a mix of methods, ideas, histories, and, yes, even philosophies.

History teacher in

History teacher in

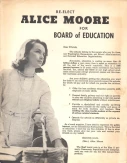

I don’t think so. Historically, the fight in school politics has always been for the middle. Whoever can prove she is fighting for better schools will win. Alice Moore won in West Virginia in 1975 by fighting for better textbooks for students. She won by convincing enough neighbors that she represented better schools, the “best academic education possible.”

I don’t think so. Historically, the fight in school politics has always been for the middle. Whoever can prove she is fighting for better schools will win. Alice Moore won in West Virginia in 1975 by fighting for better textbooks for students. She won by convincing enough neighbors that she represented better schools, the “best academic education possible.”