What does the Bible DO in America? What does it mean for fundamentalists to say that the Bible used to be—and ought to be again—“America’s Book?” Let’s start by taking a quick look at some stories from history and culture that help demonstrate the complicated role played by the Bible in American public life.

Story #1: November 22, 1963. With President Kennedy shot dead, the Secret Service scrambled to protect Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson. He was hustled off to the airfield, riding low to keep his head down. Once Jacqueline Kennedy arrived, the swearing-in process went ahead on the overheated, overcrowded Air Force One. In order to make the inauguration official, a few things were required. They needed someone to perform the ceremony. LBJ tapped local judge and loyalist Sarah Hughes. They needed to record the ceremony for proof of its legitimacy. Someone found a Dictaphone that could serve in a pinch. And they needed a Bible. They searched the plane and found a Roman Catholic missal that had been a gift to the late President. It would do.

Story #2: Anywhere in America, anytime. Take a drive in any part of the country. Look at the road signs. If you’re lazy, just look at some maps. You can’t drive far without hitting a Bethel, or a Salem, or a Mt. Horeb, or any of a thousand more Biblical names.

But the question remains: so what? What does it mean that lots of people who founded towns often named them after Biblical places? What does it mean that in order for a President to be sworn in—even in desperate emergencies—people grabbed the Bible-est looking book they could find? Does this mean we live in a Biblical society? Or does it simply show that the Bible is a kind of inherited intellectual wallpaper for our culture?

Let’s take another look at our stories and see what we can deduce. First, what does it mean to have our physical landscape dotted with Bible-named towns? In the central New York region in which I live, these kinds of towns dominate the landscape. But they are not the only kinds of town names. Just a little north of me there is a cluster of towns named for ancient Greek places: Virgil, Ithaca, Marathon, Syracuse, and so on. One early settler, apparently, was a classics professor at Cornell and threw Greek names around. It doesn’t make the people who live there now any more Greek than living in “Manhattan” makes people Dutch or Algonquian.

Plus, it’s difficult to imagine many Americans these days really care about the Biblical roots of their landscape markers. In Wisconsin, for instance, Mt. Horeb is better known these days as the source of fancy mustard than as a descendant of the place where Moses received the Ten Commandments. Nevertheless, we must admit it tells us something about the Biblical nature of our public culture that so much of our landscape is identified this way. If place names are a jumble of history and culture, with places named for early settlers, for Indian names or mistaken interpretations of them, for strands from culture and religion…we must admit that the most common religious strand for these kinds of names is Biblical. If it doesn’t tell us much about life in Salem, or Bethel, or Mt. Horeb, it does tell us something about the cosmography of the first settlers of those towns. When they reached into their intellectual toolbox to find names for their muddy new towns, they found them in the Bible. Imagine, for instance, if those place names came from a different religious tradition. Instead of driving through Eden, Mt. Sinai, and Bethel, what if we drove through Singri, Bangalore, and Chitti? Of course, that would not make our culture Hindu any more than Biblical names makes it Biblical. But it DOES tell us something about the cultural and religious history of our landscape.

Fundamentalists might tell us that our culture is rooted in the Bible and Biblical place names are evidence of the deep organic roots of Biblicism in American culture. They might argue that the town founders of places like Mt. Horeb established themselves as the successors of Old Testament populations trembling in the felt presence of a Living God. Even if we disagree, I think it goes too far to dismiss the importance of the sacred history of our named landscape too blithely. Along with other important cultural roots, the Bible has stamped its cultural importance on our maps. It might not make the people living there Biblical, but it demonstrates at least that one of the wellsprings of American culture has long been the Bible.

But what about LBJ? Why does it matter that he was sworn in on a Catholic missal? As politico Larry O’Brien later remembered, the scene on Air Force One was chaotic. It was hot, overcrowded, somber, and anxious.

There was a sense of trauma and threat. As the plan coalesced to inaugurate LBJ right then and there, aides scrambled to provide the officiating judge with a Bible. That, after all, had been the tradition. Though recent scholars and activists have insisted that Washington never really did so, (see comments below) most of the folks on Air Force One likely believed that Washington had added “So help me God” to the Oath of Office, then bent humbly to kiss the Bible.

There was a sense of trauma and threat. As the plan coalesced to inaugurate LBJ right then and there, aides scrambled to provide the officiating judge with a Bible. That, after all, had been the tradition. Though recent scholars and activists have insisted that Washington never really did so, (see comments below) most of the folks on Air Force One likely believed that Washington had added “So help me God” to the Oath of Office, then bent humbly to kiss the Bible.

Despite what later conspiracy theorists might claim, there is no Constitutional reason why LBJ—or any President—really needed a Bible to make the Oath official. The first President Roosevelt, for instance, did not use a Bible for his swearing-in, nor did John Quincy Adams. But as in so many things Presidential, tradition meant at least as much as Constitutionality. Whether it began with Washington or only with Chester Arthur in 1881, the Kiss-the-Bible-So-Help-Me-God tradition has persisted through the twenty-first century.

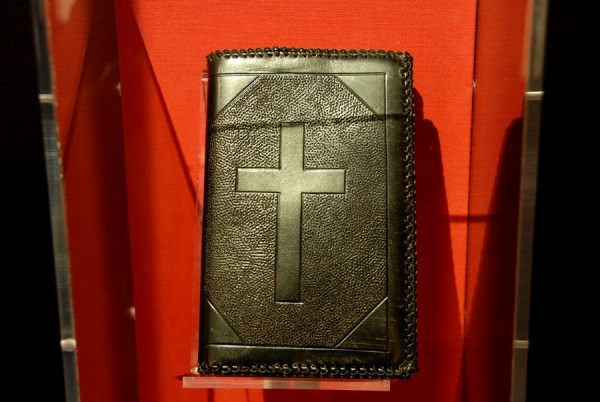

So in order to make LBJ’s inauguration feel more official, more legitimate, the folks on Air Force One that November day felt they needed a Bible. But here’s the kicker: they didn’t use one. Instead, they found a Roman Catholic missal that President Kennedy had on board the plane. According to Larry O’Brien, he assumed at the time that it was a Bible. After all, it had all the markings: a leather-y binding, a prominent cross on the cover.

So what does this mean for understanding the role of the Bible in Fundamentalist America? Like Biblical place names, it is a complicated story. First of all, it demonstrates the powerful symbolism of the Bible as America’s official book. To become President, it is traditional, though not required, to swear on a Bible, or even on two, as did Ike, Truman, and Nixon. So, in other words, when it comes to important, official acts, a Bible is the most prominent public book in America.

Consider other possibilities. The President might swear an oath on the Constitution. That, after all, is the document the new President is promising to defend. Nevertheless, in our tradition, when any promise is meant to be serious, it is sworn on a Bible, or even a stack of them. But when people on Air Force One found a Bible, it wasn’t actually a Bible at all. A missal is a collection of prayers connected to the Catholic sacred calendar. It is a religious book, to be sure, but not actually a Bible. Yet no one on Air Force One cared, or thought to check to make sure the book was an actual Bible. That tells us something about the role of the Bible in America’s cultural imagination. A Bible, for those folks on Air Force One, meant a religious book, a physically big book with a cross on the cover. They wanted, in other words, something that LOOKED like a Bible. It didn’t need to contain the actual words of the Bible to serve its purpose as an officializer of the inauguration. The Bible, in this context, is more of a symbol of a Bible than an actual collection of specific sacred scriptures.

This is not the way Fundamentalists think of the Bible. For Fundamentalists, the words of the Bible matter. The fact that Presidents take their oaths of office on a Bible may reassure Fundamentalist America that their Bible is (still) America’s official book. But for lots of other Americans, the Bible is just a symbol of a big, official-looking, historic-looking book. The words themselves don’t really matter. Presidents, in this view, are not swearing to enforce Biblical truths, but only following a quaint but harmless tradition in taking an oath on a Bible. This complicated double meaning of the Bible in public life will be the subject of the next few posts here at ILYBYGTH. At the very least, we agree that the Bible is not just another book for Americans. The Bible, like Biblical place names, has a unique role as part of the cultural wallpaper of American life. But not necessarily as the religious guidebook that Fundamentalists want it to be.

Ray Soller

/ March 10, 2012Adam, even though many different sources, over the last century and a half, have taken it for granted that George Washington added a four-word religious codicil to his presidential oath, there’s actualy no proof to this story. There’s a 1/29/2012 USA Today article by Cathy Lynn Grossman article at http://www.usatoday.com/news/religion/2009-01-07-washington-oath_N.htm that reports on this very subject. A reality check shows that most presidents are not known to have inflated the presidential oath by adding “So help me God” to their oath of office. In fact, we have to wait for the the early part of the twentieth century to find the first Elected-President who is reliably known to have done so, and it’s only since FDR’s 1933 inaugural ceremony that all presidents have followed this so-called “So help me God” tradition.

When it comes to a president’s swearing his oath on a Bible and kissing it at the end of the oath, this ritual is not likely one that Washington had chosen for himself. No one knows exactly why a Bible showed up at Washington’s first inaugural ceremony, but it is likely that Chancellor Robert Livingston administered the oath according to New York State legislative requirements. We do know that Washington did not plan for a Bible during his second inaugural ceremony and that there are no reports of a Bible having been used. It appears that Andrew Jackson is the first president who actually chose to include a Bible as part of the oath ceremony. Consequently, even from Washington’s first inauguration, the complete “Kiss-the-Bible-So-Help-Me-God” so-called tradition was more of an exception than the general rule with Harding and Truman being the only true exceptions.

Best regards,

Ray Soller

adamlaats

/ March 10, 2012Ray,

Thanks for pointing that out. I stand corrected! I will fix my post to reflect this. Ray’s comments also led me to some other convincing sources, such as this article on History News Network by Peter Henriques: http://hnn.us/articles/59548.html

Interested ILYBYGTH readers should check out Ray’s entries over at American Creation: http://americancreation.blogspot.com/2009/01/so-help-me-god-george-washington-myth.html

adamlaats

/ March 10, 2012NB, Ray also alerted me to another article that might be of interest on the topic. Mathew Goldstein of Secular Perspectives offers an argument against the notion that Presidential tradition demanded God or Bibles at inaugural events: http://secularhumanist.blogspot.com/2011/07/religious-references-in-presidential.html