Well, we had a good run. For the past hundred-fifty years or so—depending on where you live—Americans have had public schools. I don’t mean to be Chicken Little here, but from an historical perspective, it looks like Queen Betsy has figured out a way to get rid of em.

In some senses, of course, the United States has always had schools FOR the public. Even before the Revolution, there were schools that students without tuition money could attend. I’m finding out way more than I want to about the funding of early American “public” schools in my current research. As I’m finding, these “charity” schools had a wild mix of financial backers. Churches, taxpayers, wealthy individuals, and even not-so-wealthy people gave a lot or a little to educate impecunious children.

At different times in different places, a funding revolution swept the world of American education in the 1800s. Basically, this revolution replaced schools that were FOR the public with schools that were BY and FOR the public. That is, instead of parents, charities, philanthropists, churches, and governments all kicking in here and there to fund worthy students and schools, local and state governments committed to provided tax-funded educations to children. Those governments took tax money from everyone—whether or not they sent kids to the public schools—and in return promised to run schools for the benefit of the entire community.

There were big problems with this funding revolution. Not all children were included. Most egregiously, African-American students were often segregated out of public schools, or shunted off to lower-quality schools. And not all states participated equally. New England and the Northeast jumped early to the new model, while other regions hesitated. Plus, people without children and people who chose not to send their children to the public schools ended up paying for schools they didn’t personally use.

The heart and soul of public education, however, was that the public schools would be administered as a public good, like fire departments and roads. Everyone paid for them, everyone could use them, and everyone could in theory claim a right to co-control them. Even if your house didn’t catch fire, in other words, you paid taxes to support the firefighters. And even if you didn’t drive a car, you paid to maintain the public roads. And those firefighters and road crews were under the supervision of publicly elected officials, answerable in the end to taxpayers. Public schools would be the same way.

This funding arrangement has always been the heart and soul of public education. And it is on the chopping block. Queen Betsy recently proposed a five-billion dollar federal tax-credit scholarship scheme. Like the tax-credit scholarship programs that already exist in eighteen states, this plan would allow taxpayers to claim a credit for donations to certain non-profit organizations that would then send the money to private schools.

In some cases, donors can claim up to 100% of their donations back. For every dollar they “donate,” that is, they get a full dollar rebated from their tax bills. Tax-credit scholarship schemes serve to divert tax money from public education—administered by the public—to private schools without any public oversight.

[Confused? Me, too. For more on the ins and outs of tax-credit scholarships, check out this episode of Have You Heard, featuring the explanations of Carl Davis of the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.]

Back to this future?

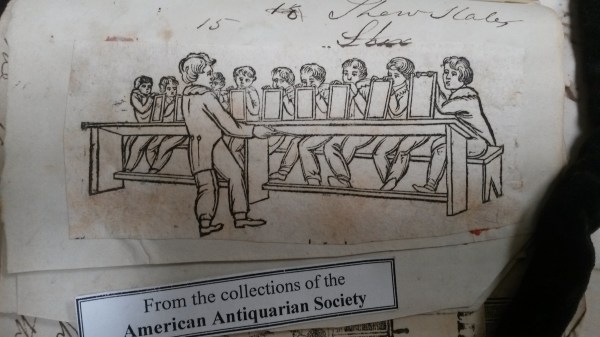

What’s the big deal? In essence, these schemes return us to the world before the public-education $$$ revolution. They return us to the world Joseph Lancaster knew so well in the first decades of the 1800s, where funding for schools was an impossibly tangled mess. Back then, parents who could afford it could send their kids to great schools. Parents who couldn’t had to hope their kids might get lucky and attract the attention of a wealthy philanthropist or a church-run charity program. They had to hope that a mix of government money, private tuition, church support, and philanthropist largesse could support their kids’ educations.

By allowing taxpayers to pick and choose whether or not to support public education, Queen Betsy’s proposal takes us back to those bad old days. Are we really ready to throw in the towel on public education? Ready to return to the old system, with “charity” schools run FOR the public by wealthy benefactors who wouldn’t send their own kids there?

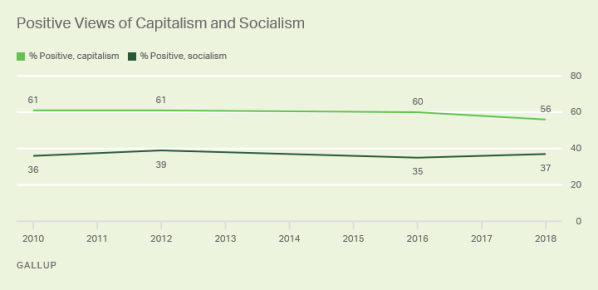

As Alexander asked in the pages of the Monitor Herald (Calhoun City, MS), January 3, 1963, “Have you ever heard or read about a more subtle way of undermining the American system of work and profit and replacing it with a collective welfare system?”

As Alexander asked in the pages of the Monitor Herald (Calhoun City, MS), January 3, 1963, “Have you ever heard or read about a more subtle way of undermining the American system of work and profit and replacing it with a collective welfare system?”