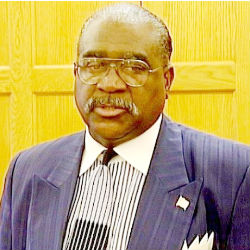

What would a President Carson mean for education?

Recent reporting in the New York Times asks if prominent neurosurgeon Ben Carson is a 2016 GOP contender. Carson has become hugely popular among conservatives. In a recent speech at Conservative Political Action Conference, Carson received rousing applause when he mentioned that he had some good ideas . . . “if you should magically put me into the White House.”

Conservatives at CPAC loved Dr. Carson. They should. Carson has a dramatic life story and is a compelling public speaker. His values are profoundly conservative. He wants more public religiosity. He wants a flat tax and a smaller public debt. He wants America to beef up its military strength and return to a vision of the past in which Americans shared common values.

New York Times reporter Trip Gabriel noted that a recent Carson speech at a National Prayer Breakfast “criticized the health care overhaul and higher taxes on the rich, while warning that ‘the PC police are out in force at all times.’” True enough. But those were just the starting points and final words of Carson’s half-hour talk. By far the bulk of Carson’s address concerned the vital importance of education.

I wonder if reporter Gabriel ignored the bulk of Carson’s speech because Gabriel considered education to somehow be of lesser political interest than health care and tax policy. If that’s the case, Gabriel couldn’t be more wrong.

Check out the speech itself if you have thirty minutes to spare. You’ll see that Dr. Carson focused almost entirely on traditional conservative themes in educational policy and reform.

First of all, Carson lamented the sad state of American public education. Citing statistics about high high-school dropout rates and low college completion rates, Carson deplored the fact that too many Americans are not getting a good education. This had echoes of the ugly history of slavery, when it was illegal to educate a slave. The lesson, Carson insisted, is clear: “When you educate a man you liberate a man.”

Carson shared his own remarkable educational history. As a child, he grew up in a very poor household. His mother had been married at age thirteen, soon abandoned by her bigamist husband. She herself had only attained a third-grade education. But she insisted ferociously that her two sons would be different.

She required young Ben and his brother to write two book reports per week for her to review. Eventually, of course, Dr. Carson went on to his spectacular career as a leading pediatric neurosurgeon.

In Carson’s prayer-breakfast speech, he argued that Americans had always loved formal education. But recently, Carson complained, “We have dumbed things down.”

That is not okay, Carson insisted. America’s form of government requires a well-informed citizenry. That is why Dr. Carson offers two programs for low-income youth: a college scholarship fund and reading rooms in low-income public schools.

Education, Carson promised, will prevent criminality.

More important, education will prevent cultural decay and decadence. Look at Ancient Rome, Carson said. “They destroyed themselves from within. Moral decay, fiscal irresponsibility.” The same thing could happen to the United States, Carson worried, if we don’t beef up our education system.

So what would a President Carson do for education? Could he combine traditionally leftist education policies—such as financial assistance for the lowest income schools and students—with traditionally rightist policies—such as teaching traditional values and public religiosity in schools?

Even the superhuman brain surgeon himself couldn’t answer that. But it is worth more consideration than some journalists and commentators seem willing to give it.