What should teenagers be learning about sex? It is a perennial question at the center of our educational culture wars. A recent controversy from California’s Bay Area shows how this old battle has changed, and how it has stayed the same. This time, parents in Fremont, California objected to a sex-ed textbook they found too racy. After parent protests, the district pulled the book.

As I note in my upcoming book about educational conservatism in the twentieth century, the pattern seems familiar: A textbook includes explicit information about sex. Parents object. The administration buckles, allergic to any whiff of controversy. Progressives lament the parents’ Victorian attitudes toward sex. Conservatives crow that their children are being pimped by an educational establishment that does not respect their values.

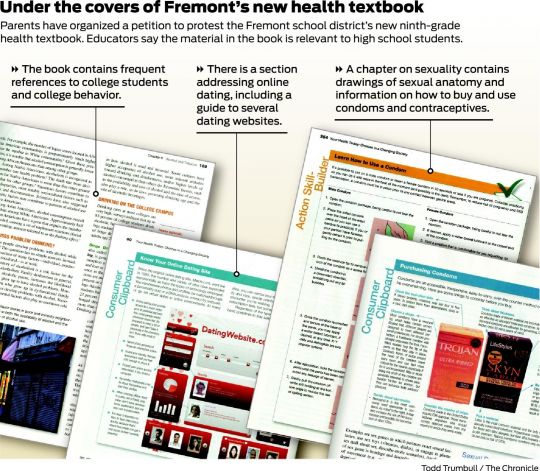

That script certainly seems to be playing out in Fremont, but there are some wrinkles. The textbook, Your Health Today, contained a twenty-page section on sexual behavior. As the parent petition protested, this section included information about more than just the mechanics of sex. It told students about

sexual games, sexual fantasies, sexual bondage with handcuffs, ropes, and blindfolds, sexual toys and vibrator devices, and additional instruction that is extremely inappropriate for 13 and 14 year-old youth.

And, as in similar controversies in the past, the protesting parents quickly reached out to national conservative activist organizations for support. In this case, Fremont parents contacted the conservative Christian Pacific Justice Institute for back-up.

But the “conservative” parents made clear that they did not oppose sex ed in general. What they did not like was the inappropriate college-level sex ed this book contained. Parent activist Asfia Ahmed told the Christian Post that the problem was not sex ed as such; the problem was that this book in particular “speaks to adults; it does not speak to teens and adolescents.”

Predictably, progressive commentators accused conservatives of being trapped in the past. As one writer noted, “It’s frustrating that this is still controversial.” I personally agree. I’m a teacher and parent. I want my students and daughter to have frank, explicit information about sex. And I think that such information needs to include some sense of the wide variety of sexual behaviors that are common in our society. It needs to include the basic fact that sex should be pleasurable and should never be coerced. Perhaps most tricky, I think that public schools have a duty to convey this information. After all, with pregnancy and HIV on the line, these are literally life-and-death subjects.

But the notion of some anti-conservatives that these issues have been resolved in the past demonstrates the dunderheadedness of my fellow progressives. Some progressive commentators seem to think that these debates have already been settled. Whether the issue is sex ed, school prayer, or creationism, progressives often express surprise that these questions are “still” controversial. Such attitudes demonstrate the ignorance of progressives.

Conservative notions about sex ed in public schools have always had a decisive influence on the goings-on in those schools. In this case, for instance, we see how quickly the administration caved to parent protests. Here and elsewhere, the notion that there is some healthy connection between kids and sex is a very touchy one in our society. Conservatives need only say that a book goes too far to have that book quickly yanked by the district.

Perhaps the hard-hitting journalists of the Today Show made the most salient point about this story. They interviewed some of the young teenagers who would have read this textbook. As one told them, “Like ewwww. . . . I don’t really feel like I need to know about that right now.”