Conservatives might be shooting their guns in the air to celebrate. Progressives might be shedding a tear in their IPAs. Whether it’s a triumph or an apocalypse, it’s not a surprise: The Ed Department is filling its ranks with more and more conservative, creationist leaders. Before we freak out, though, let’s take stock of the real situation.

First, the creationism part. The new pick for the education department’s undersecretary has made no bones about his creationist sympathies. As head of South Carolina’s schools, Dr. Mick Zais supported the removal of the idea of natural selection from the state’s science standards. As Zais told a local newspaper, “We ought to teach both sides and let students draw their own conclusions.”

It’s not only creationism. Queen Betsy’s pick for undersecretary of education will make conservatives happy for a lot of other reasons as well. Zais comes to the nomination fresh off his post as South Carolina school superintendent. As Politico reports, Dr. Zais became a conservative ed hero for refusing to truckle to the Obama administration’s carrots and sticks.

In South Carolina, Zais pushed hard for vouchers. Time and time again, vouchers are embraced by conservatives who hope to shift public-school money to private schools, often religious schools.

When Zais’s zeal is added to DeVos’s enthusiasm, it might seem to progressives and conservatives alike that conservatives have finally triumphed in the world of educational politics. If ILYBYGTH cared about clickbait, we would certainly write something that exploited that sort of attitude. But we don’t and we won’t. Because, in historical perspective, this moment of conservative triumph looks much less triumphant than it might seem at first.

First, let me repeat the caveats SAGLRROILYBYGTH are sick of hearing: My own politics skew progressive. I think creationism has no place in public-school science classes. I am horrified by Queen Betsy and I think President Trump’s leadership is a blight on our nation that won’t be easy to recover from.

Having said all that, I’m not interested this morning in fighting Trumpism but rather in understanding it. And when we see Queen Betsy’s reign from the perspective of the long history of conservative activism in education, we see just how wobbly her throne really is.

First, as I noted in my book about twentieth-century educational conservatism, today’s conservative push for charters and vouchers is both a novelty and a concession. Milton Friedman promoted the idea of charter schools way back in the 1950s, and nobody listened. Even the free-marketiest of Reaganites didn’t care much about promoting alternatives to traditional public-school funding.

Take, for example, Reagan’s second ed secretary, William J. Bennett. He was far more interested in pushing traditional moral values and classroom rules in public schools than in gutting public-school funding.

What happened? Only in the 1990s did conservative education pundits embrace the notion of charters and vouchers. They did so not as a triumph, but as a grim concession to the obvious fact that they had been stumped and stymied by their lack of influence in public schools.

So when conservative heroes like Queen Betsy and Superintendent Zais push for alternatives to traditional public schools, progressives should fight back. But we should also recognize that the conservative drive to fund alternatives results from conservatives’ ultimate failure to maintain cultural control of public schools.

Plus, the language used by conservatives these days represents another long-term progressive victory. In his public argument for voucher schools, for example, Superintendent Zais voiced his agreement with progressive ideas about the purposes of schooling and public policy. Why should we have more vouchers? Quoth Zais, vouchers will provide “more options for poor kids stuck in failing schools.”

I understand Zais may be less than 110% sincere in his zeal to promote social equity through public school funding. Nevertheless, the fact that he felt obliged to use that sort of progressive reasoning shows how dominant those progressive ideals have become.

In other words, if even South Carolina’s conservatives adopt the language—if not the authentic thought processes—of progressive thinking about the goals of public education, it shows that progressive ideas have come to dominate our shared beliefs about public education.

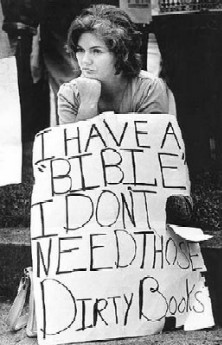

On the creationist front, too, Zais’s conservatism shows the long-term decline of conservatism. It wasn’t too long ago, after all, that creationists fought and often won the battle to have evolution utterly banned from public schools. These days, all Zais can dream of is maybe wedging some worse creationism-friendly science into public schools alongside real science.

Science educators won’t like it. I don’t like it. But once again, before we freak out, we need to recognize the long-term implications of our current situation. The dreams of creationists are so far reduced they no longer preach the abolition of evolution. If you ask creationist leaders these days what they want in public schools, they’ll tell you they want children to learn evolution, “warts and all.”

We don’t agree about that. And we don’t agree about the value of vouchers. I’m not even ready to concede that Dr. Zais and I agree on the best ways to use public schools to help alleviate poverty and improve the economic life chances of kids in lower-income families.

And I’m perturbed. I’m frightened by Queen Betsy. If he’s confirmed, I’m guessing I’ll be alarmed by Dr. Zais’s work.

I also know, though, that the seeming strength of conservative thinking these days is an illusion.

Soon, the young Lancaster started believing his own fundraising spiel. He promised the leaders of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia that his master plan could work in any school, anywhere. It couldn’t and it didn’t. The mistake Lancaster made—one of them, at least—was to assume that his limited successes were due to the specific methods he was using, rather than to his endlessly deep royal pockets and his authentic love and enthusiasm for his school and students.

Soon, the young Lancaster started believing his own fundraising spiel. He promised the leaders of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia that his master plan could work in any school, anywhere. It couldn’t and it didn’t. The mistake Lancaster made—one of them, at least—was to assume that his limited successes were due to the specific methods he was using, rather than to his endlessly deep royal pockets and his authentic love and enthusiasm for his school and students.