Why do so many white evangelicals support President Trump? Not just in a passive, least-worst, anyone-but-Hillary sort of way, but actively and even enthusiastically? Why have some white evangelical leaders become what historian John Fea calls “court evangelicals?” After all, President Trump is no one’s idea of a Christian. One recent argument ties evangelical Trumpism to faith, but not surprisingly, I think it has a lot more to do with historical imagination. For people who fantasize about a lost American “Shining City upon a Hill,” Trump’s “take-back-America” rhetoric punches important buttons.

It’s the hat, stupid.

Over at Religion Dispatches, Eric C. Miller interviews Kurt Andersen about Andersen’s new book Fantasyland: How America Went Haywire. I haven’t read the book yet, but I’ve got it ordered. It sounds fantastic and I’m looking forward to reading the whole thing.

I can’t help but spout off a little, though, about some of Andersen’s arguments in this interview. Andersen describes his explanation of the odd relationship between the starchy moralists of America’s evangelical subculture and the wildly careening leadership of President Trump. Andersen makes connections between charismatic belief and Trumpism, but I think there’s a much more obvious and important explanation. Trump appeals powerfully not to anyone’s ideas about God and worship, but rather to white evangelicals’ implicit vision of American history.

On a side note, I couldn’t help but shudder at one of Andersen’s other statements. Like a lot of pundits, he makes some major goofs about the nature of creationism these days. As Andersen puts it,

Just in the last 15 years, it has become Republican orthodoxy to disbelieve in evolution and to challenge evolution instruction in the public schools. This is a uniquely American phenomenon, and it is a product of a religious tradition that, starting about a half a century ago, decided to make that stand in favor of creationism.

I added the emphasis to point out the problem. Andersen’s not alone on this point, but he is deeply wrong. Radical creationism’s political oomph is not at all uniquely American. To cite just one example, Turkey’s government has made even more aggressive moves in favor of creationism. This is not a minor error, but a major misreading of the nature of modern creationism. As I’m arguing in my current book, following in the footsteps of the great historian of creationism Ron Numbers, radical young-earth creationism is not “uniquely American,” but rather a popular and politically potent response to the dilemma of post-modern life, worldwide and across many religions.

That’s a big intellectual problem, but it is not my major beef with Andersen’s argument this morning. No, the real question today is about the relationship between America’s politically active white evangelical Protestant community and the shoot-from-the-hip political style of President Trump. How could it happen?

For Andersen, the connection can be tied in part to one wing of evangelical belief. For charismatic Christians, Andersen explains, belief in the unbelievable is part and parcel of their culture of dissent. Here’s how Andersen made his point, with emphasis added:

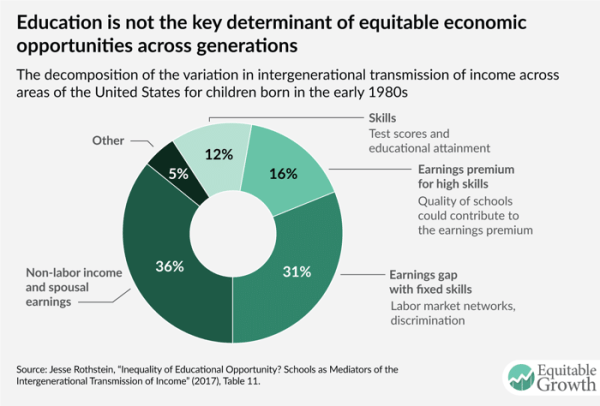

[Miller]: Then I have to ask you about Donald Trump. He is now America’s Conspiracy-Theorist-in-Chief, a position that he attained with support from 81 percent of white evangelicals. Does this research help account for that?

[Andersen]: It’s bizarre. It’s interesting, because he is not, in any meaningful sense, a Christian. So why is it that our most fervently Christian fellow citizens support him so strongly? Well, as you say, our most fervently Christian white citizens. I think there is something there—it suggests that there are other reasons, cultural and economic reasons, together with the religious motivations that are driving that support.

But for my purposes, within this Fantasyland template, I think that they have some things in common beyond resentment of the elites and some of these other traits that are not necessarily connected to belief in the untrue—a lack of respect and all that. But Trump has shown a unique willingness to embrace claims that are demonstrably untrue—that Barack Obama wasn’t born here and a conspiracy covered that up; that Ted Cruz’s father was involved in the JFK assassination; that five million illegal immigrants voted against him in the 2016 election; and on and on and on. The fact that he is so indifferent to empirical reality and so willing to stand up and embrace explanations that simply confirm his pre-existing ideas or are convenient for him because they make him seem better or his enemies worse—it’s somewhat unkind, I understand, to say that he shares that tendency with religious people, but I think that is shared.

There is no evidence that people who speak in tongues are speaking a holy language. There is no empirical evidence that faith healing works. There is no real evidence that Jesus was resurrected. I could go on. So, if believing these sorts of things as a matter of faith is central to your identity, then you might identify with a guy who is willing to take strong stands on unprovable claims. If he also shares—or pretends to share—your cultural biases and resentments, then you’re going to like him! That’s about as close as I can come to explaining this strange embrace. Certainly in terms of his lifestyle, his brutal disdain for the least among us, he is so, so unchristian. I haven’t entirely figured that out—it’s another book.

Now, I agree with a lot of what Andersen has to say. I agree that “cultural biases and resentments” are the key to understanding white evangelical Trumpism. But I disagree that we can best explain Christian Trumpism by invoking “religious motivations.”

Not that there aren’t plenty of white evangelicals who justify their Trumpism in religious language. Some leaders like to say that Trump is their modern David or Cyrus. But they wouldn’t say or even allow themselves to think that they can support Trump because they already believe in unbelievable things. I get what Andersen’s saying: If you are accustomed from your religious background to a conspiratorial or fantastic mindset you are more likely to choose and support a conspiracy-theorist president. However, it’s misleading to suggest that such religiously driven beliefs are a leading explanation for Christian Trumpism.

If it’s not mainly due to their religious beliefs, why DO so many white evangelicals actively support Trump? I think Andersen is on the right track when he talks about “cultural and economic reasons,” and “cultural biases and resentments.” As I’m arguing in my new book [have you pre-ordered your copy yet?] about evangelical higher education, a leading theme in evangelical intellectual life has been the story of evangelical exile, of being kicked out of the centers of political power. Among white American evangelicals, a unique historical vision of themselves as the true Americans has fueled a century of culture-war vitriol.

From the 1920s through today, white evangelicals have been goaded and guided by this unique sense of usurpation. Unlike other powerful religious minorities, such as American Catholics, white evangelicals tell themselves over and over again that the United States used to be solidly theirs. Unlike other religious groups—even groups that are closely connected to them by theology such as African-American evangelical Protestants—white evangelicals have been sure that they deserve to claim or reclaim their role as America’s religious voice.

In short, we can’t look to theology or faith to understand evangelical Trumpism. It’s tricky, because evangelical Trumpists will explain their decisions in the language of faith. But if we listen only to such biblical justifications, we’ll miss the far-more-important real reasons for evangelical Trumpism.

For almost a century now, white evangelicals have wanted to “take back America.” Their college campuses have been seen as both citadels and havens for an imagined real America, the kind of America from which the rest of America seemed to have strayed. When a political candidate comes along and declares his wish to “make America great again,” it resonates powerfully. Just ask Reagan.

It is this history of resentment, of a sense of historical exile, of usurpation, that best explains white evangelical Trumpism.