Albert Mohler can say what he wants. To this reporter, there is a much more obvious conclusion. For those of us who struggle to understand evangelical identity, another recent poll seems like more evidence that we can’t rely on religious ideas alone.

SAGLRROILYBYGTH are sick of hearing about it, but I can’t stop mulling it over. In my upcoming book about evangelical higher education, for example, I argue that a merely theological definition of American evangelicalism will not suffice. The reason it is so important to study evangelical colleges, universities, seminaries, and institutes—at least one of the reasons—is because these institutions make it startlingly obvious that religion and theology are only one element defining evangelical identity, sometimes a remarkably small one.

Smart people disagree. Recently, for example, Neil J. Young took Frances FitzGerald to task for over-emphasizing the political element of evangelical identity. And a few months back, John Fea called me on the carpet for over-emphasizing the culturally and politically conservative element of evangelical higher education.

And smart people will surely disagree about the implications of recent poll results from the Washington Post and Kaiser Family Foundation. To me, they seem like more proof that American evangelicals are more “American” than “evangelical,” at least when it comes to their knee-jerk responses to poll questions.

The poll asked people whether poverty was more the result of personal failings or of circumstances beyond people’s control. As WaPo sums it up,

Christians, especially white evangelical Christians, are much more likely than non-Christians to view poverty as the result of individual failings.

Now, I’m not much of a Christian, and I’m not at all evangelical, but I can’t help but think that blaming the poor’s lack of effort for their poverty is not a very Christian attitude. And plenty of Christians agree with me. According to Julie Zauzmer in WaPo, African-American Christians tend to blame circumstances by large margins. The divide stretches beyond race. Democrats tend to blame circumstances. Republicans tend to blame individual failings.

Zauzmer reached out to experts to try to explain why white evangelical Christians might feel this way. She gave Albert Mohler of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminar a chance to explain it away. And Mohler did his level best. The reason white evangelicals blame the poor for their poverty, Mohler told her, was because

The Christian worldview is saying that all poverty is due to sin, though that doesn’t necessarily mean the sin of the person in poverty. In the Garden of Eden, there would have been no poverty. In a fallen world, there is poverty.

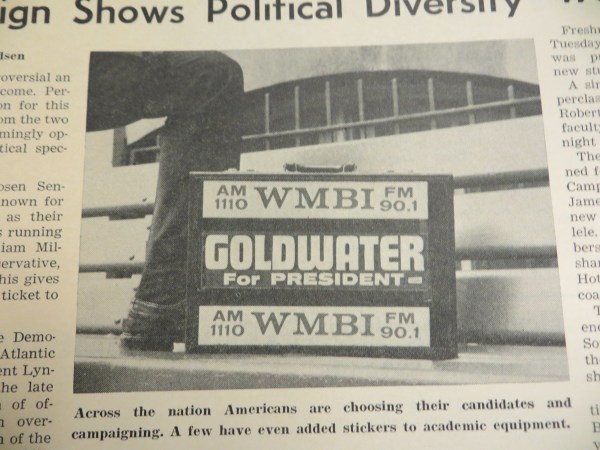

I just don’t buy it. If we really want to understand why white evangelical Americans tend to blame the poor for their poverty, we are better off looking at Reagan than at Revelation, at Goldwater than at Genesis. Blaming the poor has deep political and cultural roots. American conservatives—at least since the early twentieth century—have insisted that poverty in the Land of Opportunity must be due to individual failings rather than to structural problems in society. When American evangelicals mouth such notions, they are allowing those political and cultural beliefs to speak louder than their strictly religious or theological beliefs.

If we want to understand American evangelicalism—especially among white evangelicals—we need to understand that the “conservative” half of “conservative evangelicalism” is just as vital as the “evangelical” half. We need to understand that white evangelicals are complicated people, motivated by a slew of notions, beliefs, and knee-jerk impulses.

Why did so many white evangelicals vote for Trump? Why do so many white evangelicals blame the poor for their poverty? If we really want to make sense of it, we can’t focus on the merely religious beliefs of evangelicals. We have to look at the big picture.

If Americans really do oppose school segregation—as they tell pollsters they do—then why are schools getting more and more segregated? In The Nation,

If Americans really do oppose school segregation—as they tell pollsters they do—then why are schools getting more and more segregated? In The Nation,