It is a dilemma at the heart of Christian faith: To know or to obey? The original sin of Adam & Eve, after all, was to become as gods by eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. This week, a state supreme court judge in Oregon faced the unenviable task of ruling whether faithful people knew by faith or by fact. Not surprisingly, she punted. Especially in schools and universities, questions of knowledge and faith will continue to bedevil us all. I’m arguing in upcoming books that religious people deserve considerable wiggle room when it comes to requiring knowledge about evolution or US history, but it’s not impossible for policy-makers to be bolder than they have been.

What did you know? And when did you know it?

In the Oregon case, two parents from a strict religious sect were convicted in 2011 in the death of their infant son David. The boy had been born prematurely. The parents did not call for medical help but rather treated David at home. After nine hours, David died. Were the parents criminally liable for their faith-based failure to get medical help?

Oregon Supreme Court Justice Virginia Linder recently said yes. Sort of.

For our purposes, the most intriguing elements of this case are the tangled web of meanings in this case surrounding faith and knowledge. If the parents “knowingly” allowed their baby to suffer from treatable ailments, according to Oregon law, then they are criminally liable. But they hoped to force the state to prove that they “knew” it. They hoped to force the government to prove that they must know something that they refused to know.

Justice Linder did not decide the big question. Instead, she noted that the parents defended their actions with a different set of knowledge claims. The parents said they did not know the baby was sick. They said he appeared healthy until the very last minute. Doctors disagreed. They said any reasonable person could have discerned that the baby was in severe medical crisis.

In other words, the parents did not claim that they “knew” their faith could save the baby. They said instead that they didn’t “know” he was so very sick. The parents DID insist that the state had to prove that they “knowingly” refused care to their baby. As Linder summarized,

At trial, defendants argued that, because they withheld medical treatment from David based on their religious beliefs, the Oregon Constitution requires the state to prove that they acted “knowingly”—that is, they knew that David would die if they relied on prayer alone and, despite that knowledge, failed to seek medical treatment for him.

Justice Linder affirmed earlier court decisions that the parents were guilty of criminal neglect for their actions. The state, she ruled, did not have to prove that they “knew” of the harm they caused. But she did not decide if the parents must have known something they refused to know.

The complexity of the case shows yet again the durability of questions of knowledge and faith. Can the government insist that parents provide medical care for their children? In Oregon, yes. But can the government insist that parents “knew” their child needed medical care? That is a far more difficult question, and one that this ruling painstakingly sidesteps.

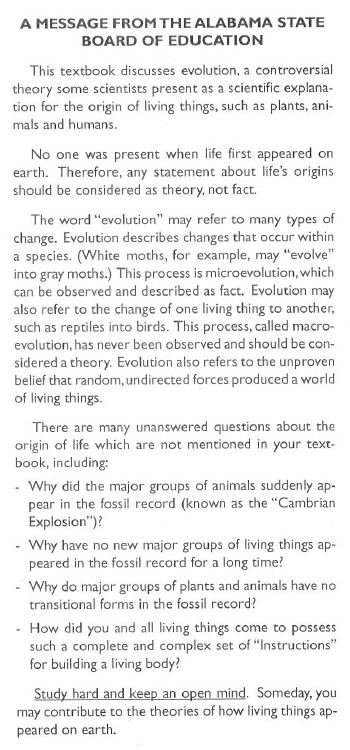

As SAGLRROILYBYGTH are well aware, nowhere do these questions of faith and knowledge clash more regularly and predictably than in the area of education. Can the government require that students “know” evolution? …that kids “know” how to prevent sexual transmitted infections? …that kids “know” how the first humans came to North America? Also, how have private schools and universities attempted to shield young people from these sorts of knowledge?

Alas, secular progressive types like me cannot relax and claim that public schools should always promote knowledge over ignorance. After all, I agree that certain types of knowledge are not appropriate for certain groups of students. For example, we should teach all children about horrifying historical episodes, such as lynching in the USA or the Holocaust. But we should not expose young children to gruesome images of charred corpses, sexually mutilated before being lynched. At least, I don’t think we should.

Such images are true. People should know about them. But I do not think seven-year-old children should be exposed to that sort of knowledge. I agree that schools should work to keep young children ignorant about such knowledge, even though I acknowledge that it is true and important.

The difference, in other words, is not that conservative religious people want to keep knowledge from children, while progressive secular folks want to give knowledge to children. The difference is only in what sorts of knowledge we want to shield students from, and how.

As I argue in a chapter in an upcoming book about ignorance and education, we can see these questions starkly exposed in the history of curriculum for private conservative evangelical schools. I looked at US History textbooks produced by Bob Jones University Press and A Beka Book. In each case, from the 1980s to the end of the twentieth century, publishers made claims about historical knowledge in each succeeding edition that were farther and farther afield from mainstream historical thinking.

Know this, not that.

In a later edition, for example, a history textbook from A Beka explained that humanity expanded around the globe after the fall of the Tower of Babel. Obviously, that is a very different explanation from what kids would read in a mainstream textbook. Publishers like A Beka hoped to shield students from mainstream knowledge about history by replacing it with an alternate body of knowledge. These textbooks do not simply try to create ignorance by blocking knowledge, but rather try to foster ignorance about a certain sort of knowledge by producing a convincing set of alternate knowledge.

When it comes to evolution, too, questions of knowledge and belief quickly become tangled and tricky. I’m arguing in an upcoming book with co-author Harvey Siegel that students in public schools must be required to “know” evolution. But too many public-school enthusiasts, we argue, have a cavalier attitude about this sort of knowledge. Yes, students must “know” and “understand” the claims of evolutionary theory. But if they choose not to believe them, that is their business.

Perhaps an easier way to make the distinction is to say that public-school students can be required to “know about” evolution. They must be able to explain it correctly. They must be able to describe accurately its main points. But if they think it would harm their religious beliefs to say they “know” that humans evolved via natural selection, then they have the right to insist that they only “know about” it.

It’s not an easy distinction. Nor was it easy for Justice Linder to decide what to say about the Oregon case. Do parents have the right to their religious beliefs? Yes. Can they not know something that everyone else knows? Yes, certainly. Do they have the right to insist on that relative ignorance if it causes palpable harm to others? Not in Oregon.

But this ruling does not decide if the parents in this case “knew” that their faith would save Baby David. It only states that parents do not have the right to insist that the government prove that they knew it.