Is it possible for conservative religious people to know and understand evolution without believing it? And, if it is possible, what does it look like? What does it mean? At the ever-challenging Cultural Cognition blog, Dan Kahan challenges the notion of “cognitive apartheid.” Do Professor Kahan’s ideas match real experience?

As the sophisticated and good-looking regular readers of I Love You but You’re Going to Hell (SAGLRROILYBYGTH) are aware, I’ve written a new book with philosopher Harvey Siegel suggesting a different approach for evolution education. Too often, the implicit goal of evolution education is to encourage student belief in evolution. Students from families who dissent are sometimes made to feel unwelcome in public schools, as if their dissent disqualifies them as science students. Instead, we argue, the goal of evolution education must be to foster knowledge and understanding of evolution. If students choose not to believe it, that is their right.

But is it possible? It seems difficult to know something and not believe it. Do I really know that 2 + 2 = 4 if I don’t believe it, like some sort of Orwellian thought-victim?

Studies of real students have shown that it is not only possible, but a relatively common practice. In 1996, W.W. Cobern suggested that resistant students commonly practice what he called “cognitive apartheid.”[1] Students who don’t want to believe the philosophical or religious implications of evolutionary theory, Cobern thought, could segregate out those ideas for use only in specific situations. When they needed to pass a science test, for example, students could pull up their knowledge of evolutionary theory, but in other contexts, they could keep those ideas separate from the rest of their thinking.

In a 2012 study, Ronald S. Hermann looked at the ways this apartheid worked in practice. Hermann located students who did well on tests of evolutionary ideas. Then he talked to two of them who knew and understood evolutionary theory very well, yet refused to believe it. “Krista” and “Aidan” both described the ways this process worked for them.

For those of us from secular or liberal religious backgrounds, these interviews provide fascinating insights into the ways conservative religious people justify their seemingly conflicted knowledge and belief. Hermann argues that the mental processes involved are “unclear and ambiguous in nature.”

For Aidan, his thorough knowledge of evolutionary science jostled along uncomfortably with his religious beliefs. As he tried to explain to Hermann,

I don’t know enough to make a real good judgment. I just try and take the Bible as its literal interpretation, and kind of leave the science stuff alone.

Krista had an even more complex relationship to evolutionary knowledge. As Dan Kahan points out, she did not simply wall off her knowledge in one segregated part of her brain. That is, she did not simply memorize a list of facts for use on rare occasions such as tests. Rather, she served as a tutor in Hermann’s class and planned a career as a veterinarian. She was able to teach evolutionary concepts to other people. And she planned to use basic evolutionary ideas in her future career. Yet she says she does not believe them.

From the snippets of her interview provided by Hermann, Krista does not seem to wall off evolutionary knowledge in her mind. Rather, she seems to be able to switch back and forth from knowing it and using it in some situations, to disbelieving it in others. Or, more precisely, she seems to know evolution in a different way. She tells the interviewer at one point, “I don’t think I, like, put my emotion into it.”

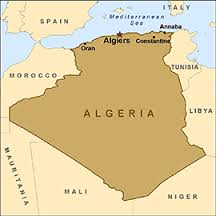

Professor Kahan wants to call this something other than “cognitive apartheid.” A better description, he suggests, is “cognitive dualism.” Some people, from Pakistan to Kentucky, seem to believe mainstream science at work, but disbelieve it at home.

In K-12 public schools, too, I think we see similar effects. Students tend to believe all sorts of things at school, then switch to a different set of beliefs at home. This is not only about controversial ideas in science, literature, or history. Rather, students do this constantly with their social identities. They might be one kind of person at school, with peers and teachers, then present a very different persona to their families at home.

As usual, I don’t have much personal experience with this kind of cognitive struggle, whether it be “apartheid” or “dualism.” Have you experienced such struggles in your life? Do you remember maintaining a dual belief system in your youth, only to move more firmly in one or another direction as you grew older?

[1] Cobern, W.W. Worldview theory and conceptual change in science education. Science Education 80, 579-610 (1996).