Maybe there’s hope for every family feud. The death of Billy Graham last week inspired an outpouring of love and respect from people whose fundamentalist forefathers loathed Graham’s revivals. Creationist impresario Ken Ham, for example, never one to water down his fundamentalist faith, had nothing but praise for Graham’s ministry. The archives tell a much different story.

Some of today’s no-compromise conservatives seem to have forgotten the legacy of their fundamentalist forefathers. Ken Ham, for example, praised Graham’s evangelistic outreach. As a child he listened to a Graham rally in Australia. As Ham recalled,

I remember people going forward in this church after listening to him and committing their lives to Christ.

Of course, it’s never kosher to speak evil of the dead. Ken Ham, however, lauded the whole body of Graham’s evangelistic outreach, from the 1950s through today. Ham included no whisper of accusation about Graham’s work.

Does he not know the backstory? Or have fundamentalists given up their ferocious feelings about Graham’s revivals in the 1950s?

Yes, there is a place to read the full story…

To be sure, Graham’s passing has attracted some criticism from intellectuals. Historian Matthew Avery Sutton blasted Graham’s reactionary politics. D.G. Hart recalls the fact that many conservative Protestants were “not exactly wild about Graham’s ministry.”

The epochal anger and denunciations sparked by Graham’s outreach, however, seem to have been forgotten by some latter-day fundamentalists themselves.

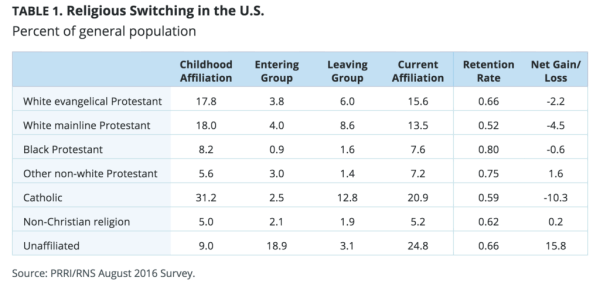

I look into this history in my new book about evangelical higher education. In a nutshell, Graham’s revivals split the conservative evangelical community. The sticking point was follow-up. At Graham’s hugely popular services, audience members who felt Jesus’s call were put in touch with a sponsoring church. Those churches included more liberal Protestant churches as well as more conservative ones.

Fundamentalists worried that Graham’s preaching was leading souls directly into the pit of hell, by sending them to false churches to learn poisoned theology. These fears weren’t limited to a few right-wing wackos; they were a prominent part of conservative evangelical thinking in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.

In 1963, for example, Samuel Sutherland of Biola University denounced Billy Graham. To a correspondent who accused Sutherland of cooperating with Billy Graham, Sutherland wrote,

I do appreciate the truth found in the Word of God which Billy Graham proclaims. We appreciate also the souls that are saved and who find their way to Bible-believing churches and thus are nurtured in our most holy faith. We deplore quite definitely, and have said so publicly, that there are so many doctrinally questionable individuals who are identified in prominent ways with the campaign and we are disappointed beyond words in the knowledge that so many of those who profess faith in the Lord Jesus Christ at the crusades will doubtless find their way into churches where the Word of God is not proclaimed and where they will not have a chance to know what the Gospel is all about or what it means, actually, to be born-again. I am with you.

In 1971, one outraged fundamentalist wrote to Moody Bible Institute President William Culbertson to express his disgust at the Graham crusades. As he put it, the Graham crusades only sent people into false churches, such as “Luthern” [sic], “Jehovah’s Witnesses, Seventh Day Adventists, Christian Scientists, etc.”

Fundamentalists didn’t like Billy Graham…

For a fundamentalist, that was a serious accusation.

Such accusations flew fast and furious around the world of fundamentalist higher education. The magazine of Biola University ran one typical reader letter in 1958. Reader Dorothy Rose condemned Graham as a false Christian and a servant of world communism. Rose warned (falsely) that Graham had been expelled from two “outstanding, sound Bible colleges.” As Rose wrote direly,

It is easy to be popular with the high-ups and with the press if we are willing to compromise. But what is the cost spiritually?

No one denounced Graham more fiercely than Graham’s former mentor Bob Jones Sr. In 1958, for example, Jones wrote to a fundamentalist ally,

No real, true, loyal, Bible friend of Bob Jones University can be for the Billy Graham sponsorship . . . . [Billy Graham is] doing more spiritual harm than any living man.

Fundamentalists have come a long way. When it comes to the legacy of Billy Graham at least, no-compromise conservatives seem to have forgiven, or more likely, forgotten the divisive nature of Graham’s ministry.