First learn to obey

HT: MM

What is the role of the child in school? Many conservative thinkers, now and in the past, have insisted that children must learn to submit to teachers’ authority. Before they can learn to read or figure, children have to learn that obedience is their proper attitude. These days, this penchant for submissive children has leached out of the world of traditionalist thinking into the burgeoning world of charter schooling. A recent interview with a leading scholar highlights the ways conservative values have reasserted themselves as the mainstream norm.

Thanks to a watchful colleague, I came across this interview with Penn’s Professor Joan Goodman. Professor Goodman works in the Teach for America program at Penn and spends a good deal of time in urban charter schools. In many of those schools, Goodman finds a rigorous standardization and a vigorous effort to train children to be submissive. As Goodman told EduShyster,

these schools have developed very elaborate behavioral regimes that they insist all children follow, starting in kindergarten. Submission, obedience, and self-control are very large values. They want kids to submit. You can’t really do this kind of instruction if you don’t have very submissive children who are capable of high levels of inhibition and do whatever they’re told. . . . They want these kids to understand that when authority speaks you have to follow because that’s basic to learning.

At the same time, Goodman notes, the schools insist on lockstep performance by teachers. Every teacher is supposed to be delivering the same content at the same time in the same way. Goodman calls it a “very uniform and scripted curriculum.”

Ask anyone familiar with urban charter-school education these days, and you’ll hear similar stories. For those of us trying to figure out what “conservatism” means in education, this leads us to some difficult questions: Did these goals and values move from fundamentalist and conservative activists into the mainstream? And if they did, how?

In my historical research into the worlds of conservative educational activism, I’ve seen it time and again. For decades—generations, even—conservative thinkers have insisted that submission is the first lesson of successful schooling. Without submissive children, teachers will not be able to transmit information. Without the successful transmission of information from teacher to student—according to this conservative logic—education has not happened.

Originally published in 1979…

In the world of Protestant fundamentalist education, youthful obedience is often elevated to a theological value. Writing for an A Beka guide in the late 1970s, fundamentalist writer Jerry Combee warned that Christian teachers must be stern disciplinarians. “If Christian educators give one inch on discipline, the devil will take a mile.” Combee continued,

Permissive discipline, for example, is wrapped up with teaching methods that always try to make learning into a game, a mere extension of play, the characteristic activity of the child. Progressive educators overlooked the fact that always making learning fun is not the same as making learning interesting. . . Memorizing and drilling phonetic rules or multiplication tables are ‘no fun’ (though the skillful teacher can make them interesting). They can have no place in a curriculum if the emotion of laughter must always be attached to each learning experience a la Sesame Street.

That same A Beka guide to good fundamentalist schooling promised that good schools always taught in lockstep. At the time, A Beka offered a curriculum for private start-up Christian fundamentalist schools. Not only would schools get curriculum infused with dependably fundamentalist theology, but

the principal can know what is being taught. He can check the class and the curriculum to make certain that the job is getting done. Substitute teachers can also step in and continue without a loss of valuable teaching time.

Some bloggers confirm that fundamentalist schooling has continued to emphasize obedience over intellectual curiosity. Jonny Scaramanga, Galactic Explorer, and Samantha Field have all shared their experiences with this sort of fundamentalist educational impulse. In their experiences, fundamentalist schools and homeschools have insisted on obedience, and have done so in a sinisterly gendered way. Young women and girls, especially, were taught to submit to male authority figures. Every student, however, seems to be pressed to submit and conform, not as a punishment, but rather as a foundation for education.

To be fair, as I argued in an academic article a while back, there has been a lot of disagreement among fundamentalist Protestants about proper education. Just as the folks at A Beka were insisting that proper education began with submission, the equally fundamentalist thinkers at Bob Jones University pushed a very different vision of proper education. Led by long-serving dean Walter Fremont, the school of education at Bob Jones promoted a more child-centered sort of fundamentalist education.

We also need to note that this insistence on submissive children is not just a fundamentalist one. Secular conservatives have long insisted that learning can only begin with obedience. In many cases, this has been a conservative response to a left-leaning progressive pedagogy. For example, leading progressive thinker Harold Rugg began his career with recommendations for proper classroom attitudes. In an article from the 1920s, Rugg instructed teachers to share authority with students. Good teaching, Rugg wrote, did not dictate to children; it did not insist on obedience. Rather, good teaching pushed students to think of themselves as autonomous, self-directed learners. Good teachers, Rugg insisted, asked students again and again, “What do you think?”

In the 1920s, this notion of proper student behavior divided progressives from conservatives. One conservative leader of the Daughters of the American Revolution offered a very different vision of good teaching. Writing in 1923, Anne Minor explained that the best teachers begin with “truth and integrity, orderliness and obedience, loyalty and love of country.”

In the 1950s, another conservative Daughter of the American Revolution warned that teaching had gone astray when it encouraged children to be “persistent in their own ideas, disobedient, and resent[ful of] parental discipline.”

Another secular conservative in the 1950s agreed. One letter-writer to the Pasadena Independent described the problems with progressive education this way:

discipline, as well as the lack of fundamental knowledge teaching [sic], is one of the biggest lacks of the progressive school. Some parents shift the discipline to the school which is wrong, of course, but if the parents are at fault for lack of discipline, so are the schools. . . . Lack of consideration of others is the biggest fault of children today, and should not be too difficult to correct. Tantrums should never be tolerated, sassiness and disobedience should be controlled at an early age.

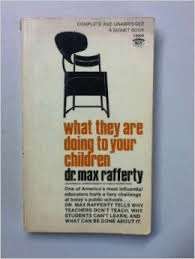

And, of course, other conservative educational thinkers and activists also pressed for an obedience-first vision of good education. The leading secular conservative voice of the 1960s, Max Rafferty, agreed that schools could only function if children first learned to submit. As Rafferty put it in his 1964 book What They Are Doing to Your Children,

School, you see, was not considered ‘fun’ in those days. It was a mighty serious business and was conducted that way. At any rate, once the two premises are accepted that (1) boys won’t behave in schools unless compelled to do so and (2) boys must be made to behave so that they can learn things that are essential for them to know, then the whole paraphernalia of corporal punishment falls into proper perspective. . . . Things have changed of late in the field of discipline, and more than somewhat. They started to change at home first, back in the twenties and thirties. The prime mover in their change was the new psychology, which was widely publicized and which caused parents seriously to doubt their proper role vis-à-vis their children for the first time in the recorded history of the human race. . . . The result was the emergence of the least-repressed and worst-behaved generation of youngsters the world had ever seen.

As I researched my upcoming book about conservative activism in education, I found this theme repeated over and over. It goes something like this: Good schooling means the transmission of information to children. That transmission cannot occur unless children submit to teachers’ authority. Therefore, any meaningful education reform must begin with the establishment of an atmosphere of relentless obedience and submission.

Professor Goodman doesn’t talk about “conservatism” or “fundamentalism” in the schools she visits. And many of the reformers these days who push for youthful obedience and teacher standardization would never call themselves conservatives, let alone fundamentalists. But it is difficult not to notice the overlap.

Conservative notions of youth and education, it seems, have become the standard way to think about educational reform among groups such as Teach For America. First and foremost, in this understanding of education and youth, children must submit.