People keep asking: Why are white evangelicals so racist? This week we see it in The Atlantic and at Forbes. At leading evangelical colleges—in the North anyway—there’s a big, obvious answer that this week’s pundits don’t mention.

Here’s what they’re saying:

- Michael Gerson wondered what happened. At his alma mater Wheaton College in Illinois, a strident anti-racism among white evangelical leaders slipped away.

- Chris Ladd places the blame on slavery and the lingering dominance of Southern Baptists. As Ladd writes,

Southern pastors adapted their theology to thrive under a terrorist state. Principled critics were exiled or murdered, leaving voices of dissent few and scattered. Southern Christianity evolved in strange directions under ever-increasing isolation.

The question should bother all of us, white or not, evangelical or not. Why do so many white evangelicals seem comfortable or even enthusiastic about Trump’s Charlottesville-friendly MAGA message?

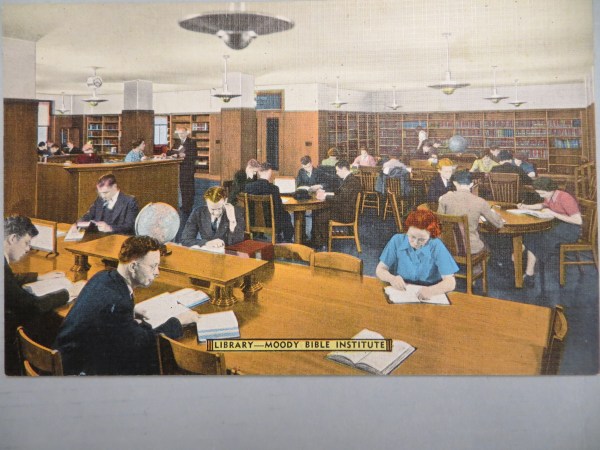

Not a lot of diversity, c. 1940s

Since neither Gerson nor Ladd bring it up, I will. At some of the leading institutions among white evangelicals, there is an obvious culprit. It’s not the political power of the slave state. It’s not craven lust for political influence. As I’m arguing in my new book about evangelical higher education, Christian colleges have always been desperate to keep up with trends in mainstream higher education. And those trends pushed white evangelicals to mimic the white supremacy of mainstream higher education.

Of course, evangelical colleges were happy to stick out in some ways. In the classroom, for example. Evangelical institutions of higher education have always prided themselves on teaching dissident ideas about science, morality, and knowledge. In social trends, too, evangelical colleges didn’t mind having stricter rules for their students about drinking, sex, and dress codes.

When it came to academic luster, however, fundamentalist academics in the first half of the twentieth century were desperate for the respect of outsiders.

At Gerson’s alma mater, for example, President J. Oliver Buswell quietly discouraged African American attendance in the 1930s. Why? There’s no archival smoking gun, but Buswell explicitly discouraged one African American applicant, suggesting that her admission would lead to “social problems.”

When we remember the rest of Buswell’s tenure, his reasons for discouraging non-white applicants become more clear. Against the wishes of other Wheaton leaders at the period, Buswell fought hard for academic respectability. He tried to decrease teaching loads, increase faculty salaries, and improve faculty credentials. As Wheaton’s best historian put it, Buswell

passionately believed that one of the best ways to earn intellectual respect for fundamentalist Christianity would be to make certain that Wheaton achieved the highest standing possible in the eyes of secular educators.

In the 1930s, that respect came from a host of factors, including faculty publications and student success. It also came, though, from limiting the number of African American students and the perceived “social problems” interracialism would impose.

Buswell and Wheaton weren’t the only northerners to impose segregation on their anti-racist institutions. Cross-town at Moody Bible Institute, leaders similarly pushed segregation in order to keep their institution respectable in the eyes of white mainstream academics.

Like other white evangelical institutions, in the late 1800s Moody Bible Institute was committed to cross-racial evangelical outreach. On paper, in any case. And MBI always remained so on paper, but by the 1950s the dean of students broke up an interracial couple. The dean was not willing to say that there was anything theologically wrong with interracial dating, but he separated the couple anyways, worried that public interracialism would “give rise to criticism” of MBI and its evangelical mission.

Why do so many of today’s white evangelicals seem comfortable with Trump and his white-nationalist claptrap? Why didn’t they hold on to the anti-racism that had animated white evangelicals in the past? Both Ladd and Gerson make arguments worth reading.

On the campuses of northern evangelical colleges, though, there was another powerful impulse. For evangelical college leaders, being a real college meant earning the respect of white non-evangelical school leaders. Between the 1930s and the 1950s, uncomfortable as it may be to acknowledge, mainstream white college leaders expected racial segregation. White evangelical college leaders weren’t more racist than non-evangelicals. They were just more desperate to seem like “real” colleges.

HT: DL, EC