What’s going on at Taylor University in Indiana? According to a recent anonymous newsletter, the evangelical campus is seething with

gossip, slander, backbiting, profanity, vulgarity, crude language, sexual immorality (including adultery, homosexual behavior, premarital sex and involvement with pornography in any form), drunkenness, immodesty of dress and occult practice.

Zoiks!

Taylor’s administration struggles to respond to this conservative carping. For those in the know about the history of evangelical higher education, this sort of anonymous poison-pen assault has always been part of life at Christian colleges.

As I found in the research for my new book, critics from both the evangelical left and the fundamentalist right have often resorted to anonymous open letters in their attempts to influence policy at their schools. The archival files bulge with letters and newsletters of this type.

At Biola University, for example, a self-identified group of disgruntled fundamentalists buttonholed President Samuel Sutherland with a list of concerns in 1969. As they wrote anxiously,

we are deeply concerned about danger signs showing themselves among some of our conference speakers and members of the student body! Indications now present seem to point to a trend that the school is moving from its Biblical foundation. May God prevent such a tragedy!

The students were concerned with the slackening of the student dress code, particularly for women. The rules stated that skirts and dresses must not be shorter than one and a half inches above the knee. As the conservative students complained, though,

the failure of a number of Biola girls to adhere to the dress rule is altogether too evident. Excessive bodily exposure of Biola girls has even been seen in the seminary section of the library and has proven a hindrance to study. . . . We urge the administration to be rigorous in enforcing the rules and regulations of Biola Schools. IN particular, the dress length rule should be observed because of its obvious Biblical basis.

Rock and roll, too, had snuck onto campus. As the protesters warned,

Unfortunately, many students here are experiencing a diet of music consisting primarily of the popular beat of the day. Our group does not advocate avoidance of popular tunes! However we do oppose the trend toward an exclusive diet of rock and roll even to the extent that our religious music is to be constructed around the beat.

All in all, the fundamentalist protesters in 1969 worried about the very continuation of Biola as a safe evangelical school. As they concluded,

Many great schools of the past today are under the sway of heresy. We do not believe that loss happened within a few months. We believe the erosion was gradual. May God help all of the administration and faculty at Biola Schools to become more alert in detecting danger signs and in taking action to prevent the deterioration that has begun here.

These sorts of anonymous pleas for reform and renewal haven’t only come from nose-out-of-joint fundamentalists. Liberal students, too, have penned their share of open letters. The archives are full of em, but my personal favorite comes from Moody Bible Institute.

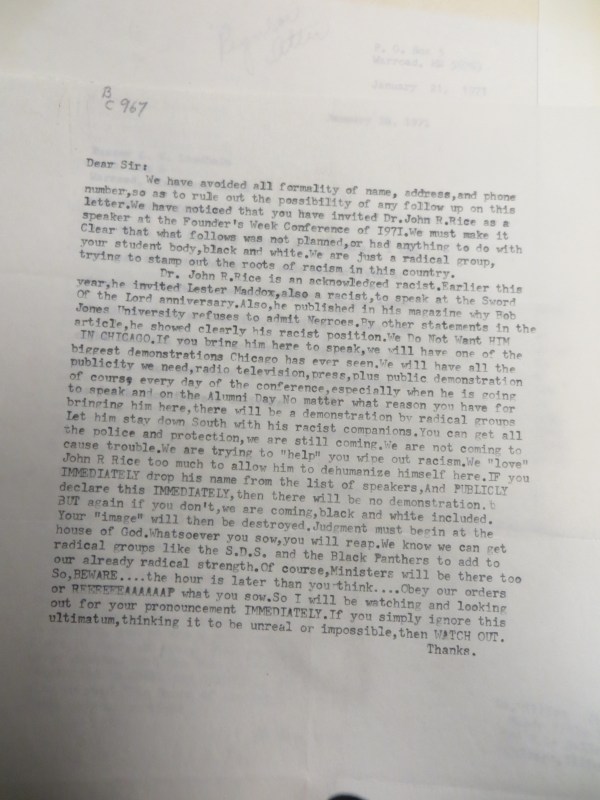

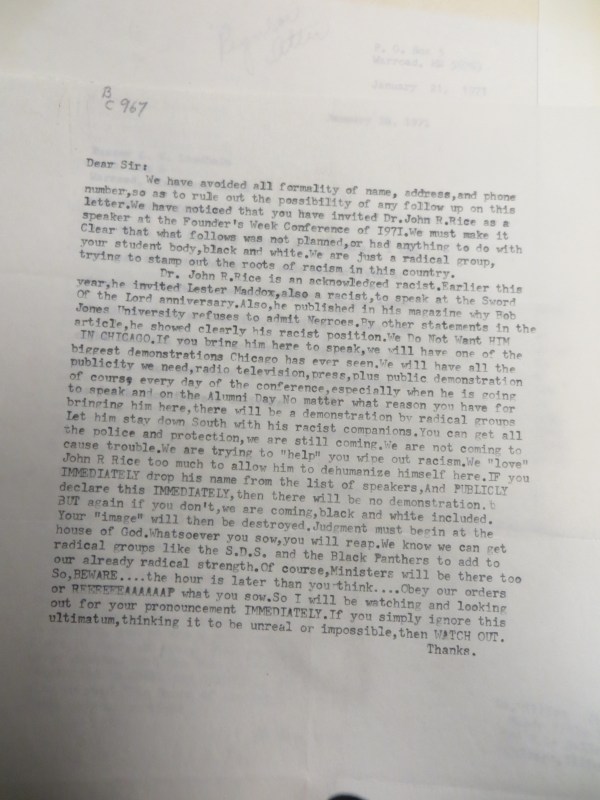

From the MBI Archives: BEWARE!

In 1971, MBI invited John R. Rice to speak at its annual Founder’s Day event. Before he could make the trip to Chicago, Rice came out in favor of the racial segregation at Bob Jones University. What was MBI to do? The leadership didn’t want to endorse Rice’s brand of Southern-fried racism. But they also didn’t want to anger his considerable fundamentalist following. As they dithered, they received an anonymous letter warning them to cancel Rice’s appearance.

The letter claimed to be written by non-students. To this reporter, however, the tone sounds awfully similar to the phrasing used by evangelical students everywhere and the letter-writers seem to know a lot more about Rice and MBI than any outsider would. For example, they had read Rice’s publication, Sword of the Lord. They knew about Rice’s recent support for racial segregation at Bob Jones U.

What should MBI do? The letter writers made threats:

We Do Not Want HIM [Rice] IN CHICAGO. If you bring him here to speak, we will have one of the biggest demonstrations Chicago has ever seen.

It would get ugly. As the letter concluded,

BEWARE . . . . the hour is later than you think. . . . Obey our orders or REEEEEEAAAAAP what you sow.

In the end, MBI canceled Rice’s speech. Perhaps the administration shared the letter-writers’ concern that their “ ‘image’ will . . . be destroyed.”

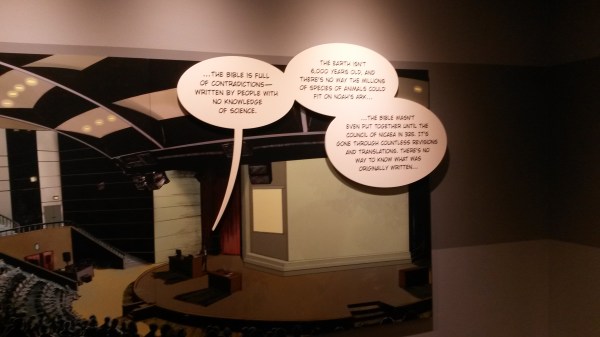

What will happen at Taylor? The conservative newsletter complains that the current campus is going to the dogs, according to Inside Higher Education. In classes, the newsletter exclaims, students learn

permissive views of human sexuality, hostility toward creationist perspectives, rejection of the rule of law (especially on the immigration issue) and uncritical endorsement of liberal-progressive ideas[.]

Such poison-pen missives have had a big impact in the past. Perhaps Taylor’s administration will take the path of least resistance and make some move to mollify the “conservative underground.”