Welcome to the latest edition of Fundamentalist U & Me, our occasional series of memory and reflection from people who attended evangelical colleges and universities. [Click here to see all the entries.] The history I recounted in Fundamentalist U only told one part of the complicated story of evangelical higher education. Depending on the person, the school, and the decade, going to an evangelical college has been very different for different people.

This time, we are talking with Kelsey Lahr. Kelsey had the experience of returning to her alma mater to teach, when she saw her school in a very different light. Today Kelsey is a writer and communication studies professor. In the summer, she works as a park ranger in Yosemite National Park. You can find links to her writing here.

If you attended an evangelical college or university and you’re willing to share your story, please contact Adam at the ILYBYGTH International offices at alaats@binghamton.edu.

Kelsey Lahr today.

ILYBYGTH: When did you attend your evangelical institution? What school did you attend?

I attended Westmont College from 2007-2011. I returned to teach there as an adjunct professor for two years, from 2017-2019.

ILYBYGTH: How did you decide on that school? What were your other options? Did your family pressure you to go to an evangelical college?

I was looking for a Christian college because I was interested in the possibility of pursuing vocational ministry as a career path. I looked at a number of evangelical colleges across the country, but was most familiar with Westmont and most drawn to it. My mom and older sister had both attended Westmont, although my family never pressured me to attend a Christian college. Ultimately I decided on Wesmont because I had such positive experiences visiting my sister there. The small class sizes and close-knit student community seemed like a good fit for me. I think my parents were actually a little surprised that I opted for a small, Christian school only an hour and a half from my hometown, but they were supportive, and would have been no matter kind of college I might have chosen.

ILYBYGTH: Do you think your college experience deepened your faith? Do you still feel connected to your alma mater? What was the most powerful religious part of your college experience?

I do think Westmont deepened my faith in some ways. I’m not a person for whom faith comes easily, and I spent my whole life questioning everything I was ever taught, including my family’s faith commitments. At Westmont, I encountered brilliant, open-minded faculty members, many of whom were politically liberal. They showed me that I could think deeply, hold progressive political ideas, ask questions, and still be a Christian. Without this experience, I think I would have become bitter about the Christian church and all its hypocrisy. In those moments of disgust with the Church when I was fresh out of college, when I was ready to give up on it, I often thought back on the great examples of thoughtful, progressive Christians I had encountered at Westmont. I think this is what kept me from leaving my faith behind.

One particularly powerful religious element of my Westmont experience was a study-abroad program I took to South Africa and Northern Ireland. On this trip, we studied racial, political, and religious conflict and reconciliation. I was deeply fortunate to witness the work that Christians and other people of faith were doing to help heal divided societies, and to develop a faith-based framework for social and political engagement. This experience continues to influence me today.

All that said, I do not feel particularly connected to Westmont now. Shortly after I graduated, there was something of a mass exodus of faculty members of color because Westmont was not a hospitable work environment for them. The most influential professor I had at Westmont left during this time because it had become so difficult to exist in that space as a faculty member of color. When I went back to work at Westmont as an adjunct, it was truly a disillusioning experience. Some of the wonderful faculty I had there as a student were still around, but now I got to see up close how the administration functioned. I saw how beholden they were to conservative donors. I had been insulated from this icky reality when I was a student, but as faculty, it was like watching the sausage get made. I knew it wouldn’t be a long-term career fit for me for that reason.

ILYBYGTH: Can you give an example of the tension between donors and faculty? Between the progressive sentiment on campus and the more conservative impulse?

At the center of the college’s spiritual life is a prayer chapel in the middle of campus. The chapel is always open, and is the only overtly “religious” building on the campus. At the front of the chapel is a stained-glass window that depicts Jesus as white, standing on a globe that is positioned so that he is right on top of North America. In the past couple of years, students have begun to recognize this depiction as problematic, colonial, and inappropriately conflating Christianity with whiteness. Many students of color expressed that the centrality of this depiction on campus made them feel even more marginalized than they otherwise would in a school where white students and faculty far outnumber students and faculty of color. A group of students started a petition last semester, asking the administration to take the window out of the prayer chapel and put it somewhere less visible and less central to the community’s spiritual life. As a faculty member, it was my impression that most students either supported this proposal or didn’t really care about the window one way or the other. Yet the administration balked, and their responses always revolved around the importance of the window to Westmont’s history. (The chapel and the window were both installed in the 1970s as a memorial to the daughter of the college’s president at the time, who died in a car accident as a young woman.) The prioritization of “history” over the concerns of current students of color seems typical of the administration. And of course, older donors are the ones who care about that particular phase of Westmont’s history. You can read more about the window issue here.

Westmont’s “White Jesus”–stay or go?

ILYBYGTH: Would you/did you send your kids to an evangelical college? If so, why, and if not, why not?

I don’t have kids, so I guess I’m off the hook! But if I did have children, I suppose it would depend on the college. Not all evangelical colleges are the same. Many of my high school church friends ended up at a very conservative Baptist college, and thankfully my parents discouraged me from applying there. I would likely do the same for my own kids. Westmont was a mixed experience for me, but I think ultimately it allowed me the freedom to question my faith within a supportive context, and I would welcome that for my children as well. On the other hand, in the years since I’ve been a student, Westmont’s faculty has become a lot less diverse, which is a huge detriment to the college. If that trend continued, I would probably discourage my kids from attending. Learning from a diverse faculty was one of the major reasons Westmont was mostly positive for me, so I might instead encourage my children to go someplace where more diversity is offered–and unfortunately, that’s not likely to be an evangelical college.

ILYBYGTH: Do you still support your alma mater, financially or otherwise? If so, how and why, and if not, why not?

I donated what I could when I was a young alum. But when my favorite professor of color left Westmont and told me what was going on, I stopped donating. Knowing what I know now about Westmont’s unfortunate tendency to pander to conservative donors and alums, even to the detriment of students and faculty, I would not donate.

ILYBYGTH: If you’ve had experience in both evangelical and non-evangelical institutions of higher education, what have you found to be the biggest differences? The biggest similarities?

I have attended and taught at both public and evangelical institutions. I was surprised to find that Westmont was by far the most academically rigorous. Maybe because it’s so small (only 1300 students), my students were intensely engaged, and truly a delight to teach. That was an unexpected and welcome difference, although I doubt that Westmont’s evangelical identity is the major cause for that. I don’t really know the major cause for that level of rigor. Perhaps the high cost of tuition selected for a particularly privileged group of students who happened to have been given all the resources they ever needed to be successful academically.

A surprising similarity was the level of closed-mindedness I experienced both at Westmont and at the public university where I attended grad school. Although this closed-mindedness was shown in different ways and toward different people, it was still quite prevalent in both places. By definition, religious colleges will require certain behaviors and encourage certain beliefs. But I also found this to be the case in grad school, although in a different way. Evangelicals were openly mocked all the time by my cohort. I no longer identified as evangelical (by then I considered myself to be simply Protestant), and I could understand why evangelicals seemed so hateable, but it was still uncomfortable. Political conservatism was also verboten. I had been a progressive my entire adult life, so I wasn’t personally affected, but I kept thinking that my grad program and Westmont were both pretty intolerant of beliefs that fell outside the mainstream of the majority.

ILYBYGTH: If you studied science at your evangelical college, did you feel like it was particularly “Christian?” How so? Did you wonder at the time if it was similar to what you might learn at a non-evangelical college? Have you wondered since?

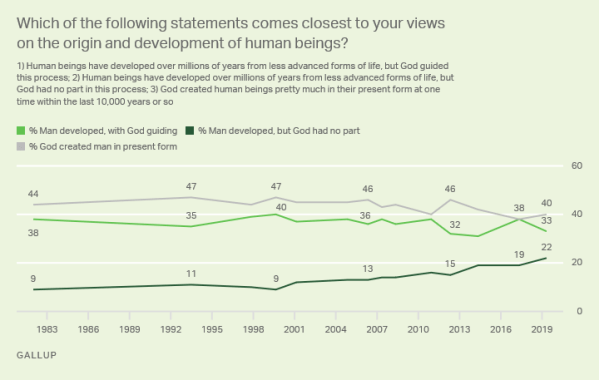

I only took one science class at Westmont, which was a basic biology class, the only one that didn’t require a lab. It was Christian to the degree that all my classes at Westmont were Christian, in that we were encouraged us to undertake our learning with the goal of pursuing God’s truth. The material itself was probably no different from what I would have learned elsewhere. The professor went to great lengths to teach mainstream evolution, but respectfully engaged with students who were offended by having their young-earth creationism challenged. In fact, I doubt many Westmont professors held a literal understanding of Genesis. Even in my Christian doctrine course, the professor spent a lot of time trying to give us a framework for reading the creation story as more metaphorical than literal, and most of my fellow students embraced this, along with standard evolutionary theory. I think this is one major factor that sets Westmont apart from other evangelical colleges. Although Westmont describes itself as evangelical, most faculty reject a strictly literal interpretation of the Bible, which puts the college at odds with one major tenet of evangelicalism. This was most apparent to me in my biology class, but also in many other classes, including theology and Bible classes.

ILYBYGTH: Was your social life at your evangelical college similar to the college stereotype (partying, “hooking up,” drinking, etc.) we see in mainstream media? If not, how was it different? Do you think your social experience would have been much different if you went to a secular institution?

My social life was nothing like the college stereotype. Westmont requires all students and faculty to sign a “Community Life Statement,” which forbids underage drinking and drinking to excess, sex outside of marriage, drug use, etc. For me, both as a student and a faculty member, it was a matter of integrity to adhere to this agreement, since I had signed it, although I didn’t necessarily agree with every element of it. So I didn’t party at all while I was in college, and once I turned 21 right before my senior year, I drank in moderation (which was allowed by the agreement). Many (but not all) students also adhered to the Community Life Statement, so for us socializing often meant movie nights, wandering the downtown area, or going to the beach. Other students did choose to party, and did so off campus. Being in Santa Barbara, not far from UCSB, those students who did want to party didn’t have any trouble finding that scene. But it happened off campus, and you had to seek it out pretty intentionally.

For me personally, I doubt my social experience would have been that different if I had attended a secular institution. Partying was never my thing. In the summers, I worked in Yosemite for the National Park Service, which was a totally secular environment and offered many opportunities to party, but I never did. Instead, I spent time socializing with other people who were happy to sit on the porch in the evenings and sip moderate amounts of wine. I probably would have gravitated to similar kinds of people at a secular college.

ILYBYGTH: In your experience, was the “Christian” part of your college experience a prominent part? In other words, would someone from a secular college notice differences right away if she or he visited your school?

The “Christian” part of my Westmont experience was certainly prominent, and anyone visiting would definitely notice. Chapel happens three times a week and is required for all students. Faculty intentionally integrate faith and learning; as a new faculty member, my department chair worked with me on this specifically. Courses in the religious studies department are also required for all students. Old Testament, New Testament, and Christian Doctrine were all required when I was a student, and still are. Faculty are also required to sign a statement of faith, although students are not. This statement of faith is not so detailed that it would exclude, say, Catholics, and many denominations are represented on the faculty, but it does ensure that all professors are practicing Christians. This means that religion is discussed openly and often, both in the classroom and in the dorms.

ILYBYGTH: Did you feel political pressure at school? That is, did you feel like the school environment tipped in a politically conservative direction? Did you feel free to form your own opinions about the news? Were you encouraged or discouraged from doing so?

I was a registered Democrat before I enrolled at Westmont, and I never felt any pressure to move right. In fact, my impression as a student was that most faculty members were at least as progressive as I was (perhaps with the exception of the economics and business department, which is probably conservative at most institutions). As a faculty member, I interacted with a greater variety of other professors than I had as a student, and my impression now is that it’s a fairly even mix of liberal and conservative, perhaps tending slightly toward the left. The student body was and is generally conservative, coming from mostly evangelical homes. But like college students everywhere, many of them move left over the course of their time at Westmont. As a student, I definitely felt free to form my own opinions about the news, and in fact I got the impression that faculty were trying to challenge students’ conservative assumptions by exposing them to a greater variety of perspectives. I saw this as a huge benefit, but then again, I was liberal to start with.

I also didn’t feel any political pressure as a faculty member. I openly taught from a progressive standpoint, and felt total freedom to do so. Critical theories were central to my teaching, and I spent a lot of time with my students examining the ways that race, class, and gender influence communication. I also incorporated a number of environmentally-focused readings into my course and assigned works by feminist scholars. A couple of students noted this in their end-of-semester course evaluations, writing that I was “extremely feminist” (this was meant negatively). Although both the provost and my department chair saw these evaluations, no one ever brought it up, which reinforced my sense of academic freedom.

ILYBYGTH: What do you think the future holds for evangelical higher education? What are the main problems looming for evangelical schools? What advantages do they have over other types of colleges?

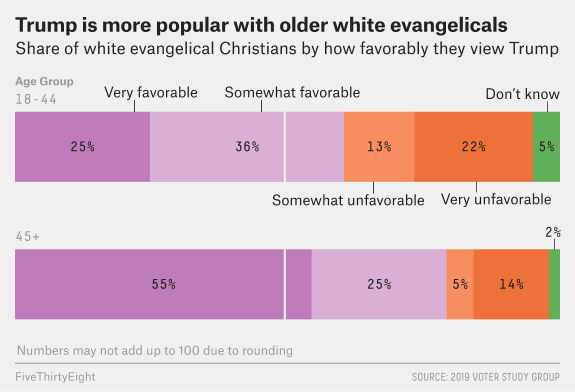

The crisis of higher education is felt across the board, and evangelical colleges are no different. At Westmont, enrollment has been down significantly in recent years, making the role of donors even more prominent. By now I recognize that all colleges and universities are beholden to donors to some extent, but Christian colleges especially are due to their generally smaller size and “niche market.” And that market is getting even more niche–young Americans are leaving the Protestant church in record numbers.[1] The reasons for this are complicated, but the trend is at least partially explained by the increasingly conservative identity associated with evangelicalism.[2] How will these trends impact Christian higher education? I believe there’s already a significant rift between progressive members of Christian colleges (including mostly faculty and some students) and conservative members (donors, administrations, and some other students). If the conservative element continues to control the purse strings, the progressive element will feel increasingly alienated, perhaps contributing to an even greater decline in enrollment. I saw this tension up close while I was teaching at Westmont, because I was the faculty adviser to the student newspaper, which is both a voice for students and is also sent to alums and donors, placing the paper right in the center of these competing constituencies. I often felt the tension between student free speech (which I prioritized) and pleasing donors (which I did not believe was my job). On one occasion I was called into the provost’s office for a stern warning when the paper published a piece of very mild satire poking fun at white privilege. It turns out that a couple of conservative alums had been offended by the piece, and the student editor in chief ended up having to issue an apology. This incident was one example of several that made It seem to me that the administration cared more about avoiding controversy and pleasing conservative donors than allowing students the opportunity to have difficult conversations in a forum that exists to foster those very discussions, especially when those conversations have to do with “liberal” issues like race, gender, and sexual orientation.

By contrast, increased political polarization might work to the advantage of some evangelical institutions that are more conservative than Westmont. Places like Liberty University will likely continue to market themselves as “safe spaces” for young conservatives, and I suspect those places will continue to draw the same faculty and students they always have. Evangelical colleges that are less overtly connected to the world of politics, like Westmont, might find themselves between a rock and a hard place as donors shape policies in a conservative direction, while students and faculty feel increasingly out of place.

[1] Cooper, B., Cox, D., Lienesch, R., & Jones, R. P. (2016, September 22). Exodus: Why Americans are Leaving Religion—and Why They’re Unlikely to Come Back. Retrieved August 9, 2019, from Public Religion Research Institute website: https://www.prri.org/research/prri-rns-poll-nones-atheist-leaving-religion/

[2] Riess, J. (2018, July 16). Why millennials are really leaving religion (it’s not just politics, folks). Retrieved August 9, 2019, from PBS website: https://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/2018/07/16/millennials-really-leaving-religion-not-just-politics-folks/34880/

Tough times for evangelical colleges, at WORLD

Tough times for evangelical colleges, at WORLD