Welcome to the inaugural edition of Fundamentalist U & Me, our occasional series of memory and reflection from people who attended evangelical colleges and universities. The history I recounted in Fundamentalist U only told one part of the complicated story of evangelical higher education. Depending on the person, the school, and the decade, going to an evangelical college has been very different for different people.

This time, we are talking with Eric C. Miller, an Assistant Professor of Communication Studies at Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania, and a contributor at Religion Dispatches and Religion & Politics. His email is emiller@bloomu.edu.

This time, we are talking with Eric C. Miller, an Assistant Professor of Communication Studies at Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania, and a contributor at Religion Dispatches and Religion & Politics. His email is emiller@bloomu.edu.

ILYBYGTH: When and where did you attend your evangelical institution?

I attended Grace College in Winona Lake, Indiana from 2000-2001 before transferring to the University of Pittsburgh.

ILYBYGTH: How did you decide on that school? What were your other options? Did your family pressure you to go to an evangelical college?

Grace College is affiliated with the Grace Brethren denomination, a conservative evangelical sect based largely in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana. I grew up in a Grace Brethren Church where I was active in the youth group. During the summer prior to my senior year, I went on Operation Barnabas, a seven-week missions trip in which 90+ Grace Brethren teenagers travel around the country in blue school buses, visiting churches and encouraging their members through Bible School-style events and performances. I had such a great time and made so many close friends that I couldn’t wait to enroll at Grace and see them again. As expected, many of them did the same. A strong minority of that freshman class had been on OB at some point in the previous three years.

Prior to taking that trip, I had planned to look around and apply to a variety of schools. But in the end I only applied to Grace. My parents didn’t pressure me, but they were glad that I was going to a solidly evangelical college.

ILYBYGTH: Do you think your college experience deepened your faith? Do you still feel connected to your alma mater? What was the most powerful religious part of your college experience?

Yes and no. I recognized from the beginning that the student body was homogenous. Everyone looked, believed, and acted more or less the same. It was an easy place to be a conservative, mid-western, white evangelical, as there was a wide support network and very few temptations. I loved being immersed in that community. At the same time, I found myself feeling a little oppositional. I was critical of George W. Bush, for instance, which was atypical. I also recall a guest lecture by Jerry Falwell, Sr. that I attended begrudgingly. Among friends, I was known as a campus liberal, but I would have remained moderate-to-very-conservative by any objective standard.

When I decided to transfer, I did so for missional reasons. I didn’t think it was good for Christian young people to be sequestered on rural campuses, so I moved to Pittsburgh to help win the world for Christ. Friends and family worried that I was making myself vulnerable to secular ideas and worldviews—which turned out to be correct—but I fancied myself a missionary. (Plus I was a little concerned that my horizons weren’t being broadened, and that I might end up married at twenty.)

Though I do think about making the trip to visit Winona Lake from time to time, I wouldn’t claim to be connected to that campus in any tangible sense. The most powerful religious part of the experience may have been leaving—I considered it a personal sacrifice.

ILYBYGTH: Would you/did you send your kids to an evangelical college? If so, why, and if not, why not?

No. I don’t have kids yet, but if or when I do I will not encourage them to go to an evangelical college. Despite my own positive experiences, I think these schools generally fail—or refuse—to provide some of the basic amenities that a college campus should offer as a matter of course. By restricting their students to a very narrow understanding of the world, policing their behavior within a very narrow moral code, and housing them within a very narrow community of the like-minded, these institutions mold their students into carbon copies of a particular type. There is no doubt that this process can be very comforting for those who participate, as long as they don’t resist. But resisting things is part of real growth, and both students and faculty should be free to stretch.

ILYBYGTH: Do you still support your alma mater, financially or otherwise? If so, how and why, and if not, why not?

No. I’m no longer conservative or evangelical, so I can’t say that I support what they’re doing. Plus they don’t send me letters anymore.

ILYBYGTH: If you’ve had experience in both evangelical and non-evangelical institutions of higher education, what have you found to be the biggest differences? The biggest similarities?

Grace and Pitt are different in just about every respect. I moved from a small, rural, almost uniformly white, conservative, evangelical college to a large, urban, diverse, secular university. They’re so different that I’m not sure the compare/contrast would even be illuminating. But I should note that the adjustment was hard. It was very easy to make close friends at Grace, and very difficult at Pitt. It turned out to be a pretty lonely time in my life.

ILYBYGTH: If you studied science at your evangelical college, did you feel like it was particularly “Christian?” How so? Did you wonder at the time if it was similar to what you might learn at a non-evangelical college? Have you wondered since?

Since I was only there for one year, I only took a collection of general education courses. But it was commonly understood that the faculty were operating on a young earth creationist model, based on a literal reading of Genesis.

Years later I had the opportunity to apply for a professorship at Grace, which I briefly considered. But the faith statement remained very rigid, and there was just no way I could sign it.

ILYBYGTH: Was your social life at your evangelical college similar to the college stereotype (partying, “hooking up,” drinking, etc.) we see in mainstream media? If not, how was it different? Do you think your social experience would have been much different if you went to a secular institution?

My social life at Grace was extremely tame. No parties, no alcohol, no drugs, no sex—any one of these things could have gotten you expelled. There were no fraternities or sororities. If you left the dorm for the weekend or overnight, you had to sign paperwork and let your RA know where you would be. It was a closely monitored environment, and your peers were just as likely as your supervisors to call out your infractions. We all knew it was oppressive, but we didn’t really care. We had signed up for this. Instead there were lots of game nights, organized sports, coffeehouse-style live music, ministry opportunities, and other forms of wholesome fun.

My social life at Pitt was different, and would have been very different if I hadn’t remained mostly the same. I got involved in the campus Christian Fellowship, but found it hard to infiltrate. On most weekends I was either out drinking (and then feeling guilty about it) or not drinking (and so staying in and relatively alone). I actually missed my Grace friends a lot when I got to Pitt. But admitting that would have meant conceding that the move had been a mistake.

ILYBYGTH: In your experience, was the “Christian” part of your college experience a prominent part? In other words, would someone from a secular college notice differences right away if she or he visited your school?

Definitely. It was an extremely prominent part—it was the prominent part. Aside from all the rules and the good clean social life, there were mandatory chapel services, ministry obligations, the curriculum-in-general, and the soft social pressures to do things like attend church weekly, volunteer for local youth groups and organizations, support the approved political propositions and candidates, etc. Grace was—and I’m sure remains—very proud of its Christian identity. That identity infuses everything and is impossible to overlook.

ILYBYGTH: What do you think the future holds for evangelical higher education? What are the main problems looming for evangelical schools? What advantages do they have over other types of colleges?

Evangelical colleges may always have prospective students as long as evangelicals continue having children—which they seem to do quite a lot! These schools are advantaged by a very coherent worldview with strict expectations for behavior and belief. Secular people tend to assume that these are liabilities, and sometimes they may be—especially among independent types, rebels, and racial or sexual minorities, for instance. But most of the straight, white, conservative evangelicals that I met—including, for a time, myself—really loved the inclusion, the accountability, and the sense of purpose that come with membership in that community. You know exactly what to do with your life, how to do it, and who to do it with. Once lost, that unequivocal sense of direction is difficult to recover or replace.

And yet, I think evangelical colleges may be headed for some of the same problems that confront evangelicalism in general. There is a disconnect between evangelical theology and culture, such that the two are very often in direct opposition. While evangelical theology hopes to represent the will of Christ—with all of the faith, hope, and love that he preached—evangelical culture is basically a subset of American conservatism—with all of its standard appeals to fear, nostalgia, and power. When this theology and this culture come into collision, white evangelicals have been far too quick to side with the culture.

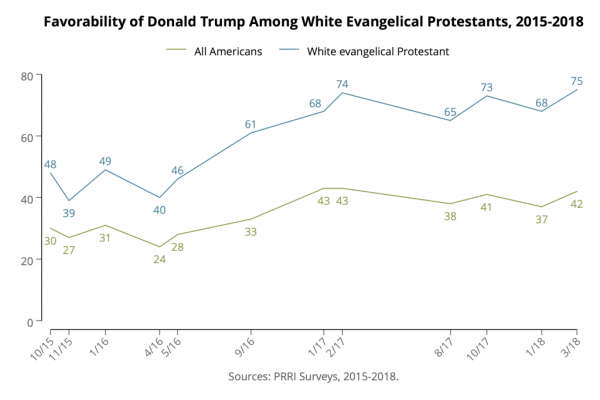

When I was a college student in the early aughts, evangelical support for George W. Bush offered the first real challenge to my faith. I struggled to square Bush Administration policy choices with the red letter teaching of Christ, so I found myself both confused and disappointed by friends and family who offered him their uncritical support. But that experience pales in comparison to what I feel today. If evangelical support for Bush left me disappointed, evangelical support for Donald Trump has disgusted me beyond words. When I awoke on Election Day and read that 81 percent of white evangelical voters had gone for Trump, a part of me died. The part of me that always wanted to reconnect with the faith of my youth—that stubborn desire to find my way home that all ex-evangelicals feel to varying degrees—just evaporated in my chest. It was a pivotal moment for me and it has fundamentally changed the way I feel about the movement and the people that I used to love.

If my experience is representative, then evangelical colleges may be confronted with declining enrollments in the years to come. If the Millennial generation is as progressive and as activist as some suggest, then even the devout may opt to avoid these culturally evangelical institutions. For their sake, and for the sake of Christian virtue, and with something like love, I find myself hoping that those numbers implode.

Thanks, Professor Miller!

Did YOU attend an evangelical college? Are you willing to share your experiences? If so, please get in touch with the ILYBYGTH editorial desk at alaats@binghamton.edu