Fundamentalists insist that America needs the Bible. As we’ve explored here before, many argue that America was founded as a Biblical nation. Fundamentalists will tell you that America went to the dogs when Americans foolishly agreed to kick the Bible out of public schools. If you have three minutes to spare, check out this video for a brief and dramatic version of this line of Fundamentalist thinking.

Fundamentalists insist that America needs the Bible. As we’ve explored here before, many argue that America was founded as a Biblical nation. Fundamentalists will tell you that America went to the dogs when Americans foolishly agreed to kick the Bible out of public schools. If you have three minutes to spare, check out this video for a brief and dramatic version of this line of Fundamentalist thinking.

As with a lot of historical claims in Fundamentalist America, this one needs some scrutiny. Outside of angry nostalgia and heated rhetoric, what can we know about the uses and meanings of the Bible in the history of America’s public schools? Educational historians agree it is notoriously difficult to find out what went on in classrooms in the past. Reading textbooks only tells us what was in those books, not what teachers and students really did. Reading memoirs of student life can tell us what students choose to remember from their school days, but it can’t get us behind that closed classroom door. And reading school laws and regulations only tell us what rulemakers wanted schools to do, not what the schools actually did. But in spite of all these difficulties, we do have scattered chunks of evidence about classroom practice in the past.

In this post, I’ll analyze one such piece of evidence. At the end of the nineteenth century, the Chicago Woman’s Educational Union conducted a survey to determine the degree to which the Bible played a leading role in American public education. In 1898, the CWEU published the results as The Nation’s Book in the Nation’s Schools. As the name implies, this was never meant to be a disinterested survey. The editor, Elizabeth Cook, planned to use her evidence to promote a vision of American public schools as the proper home of a thoroughly Biblical culture. As she wrote in her preface, Cook hoped to “aid in the beautiful work of guarding and extending the proper use of the Bible in our Glorious Educational System.” The historical vision of the Chicago group would have made today’s fundamentalist historians such as David Barton proud. Cook explained to readers that the Founding Fathers had imagined a thoroughly Biblical culture and society. In 1777, she described, the Continental Congress ordered 30,000 English copies of the Bible for public distribution. This proved, Cook argued, “how deeply the conviction that a knowledge of Biblical truth was essential to National life and health.” The Chicago women’s group decided to see if the Bible still retained a prominent role in the nation’s public schools. They surveyed state, county, and city school administrators. The results of this survey satisfied the women that the Bible did indeed remain central to American public education.

Of course, we must recognize that the responses of these school superintendents tell us more about the political nature of the inquiry than about actual Bible reading in public schools in the late nineteenth century. It shows us more about how these school politicians wanted to be seen than about what actually went on in classrooms. These survey responses framed a political statement about the proper role for the Bible in 1898’s public schools, not a neutral batch of evidence. Nevertheless, for that very reason the responses can tell us a great deal about contemporary attitudes.

The survey responses from my new home state, New York, described what Cook interpreted as a thoroughly Biblical public school culture. A significant majority (53 of 94 respondents from across the state) reported Bible reading as an opening daily exercise in their schools. Yet a sizeable minority (17 of 94) answered that the Bible was not read in their local schools.

In a neighboring state we see a similarly complicated response. The state superintendent of public education in New Jersey, one CJ Baxter, responded that most schools in his Garden State read from the Bible. Their reasons for doing so, he insisted, were simple. Baxter told the Chicago Bible women that New Jerseyans “rejoiced under the reign of God, confident that He would ‘beautify the meek with salvation.’” This answer from a state superintendent of education certainly sounds different from what one would expect from such an official today. Not only did he agree with the surveyors that the Bible ought to be part of public education, but in 1898 he publicly aligned himself with the evangelical Protestant tradition. With such attitudes at the top, it would not be surprising to find New Jersey’s teachers reading from the Bible in many public classrooms. But it would also be unsurprising to find that significant numbers of parents and teachers quietly ignored their state leader’s loud evangelicalism. It does not take a stretch of historical imagination to envision plenty of New Jersey schools in 1898 working out a far less evangelical attitude toward the practices in any given classroom. And, in fact, even Superintendent Baxter confessed that “a few” of the school boards in New Jersey did not allow Bible reading in their public schools.

From Pennsylvania, the state superintendent reported that 15,780 out of 18,109 public schools in the Keystone State read from the Bible. Such statistics delighted Cook and the CWEU. But in other places, officials reported that Bible reading would not be allowed. The curt responses from school leaders in Idaho and Utah, for example, demonstrated different regional attitudes. John Parks, Utah’s state superintendent, offered a Mormon-powered interpretation of the use of Bible in public schools. “While morality is taught and inculcated in all of the public schools of this State,” Parks told the Chicago Bible women, “the Bible is not read in any of them. The belief seems to be quite wide-spread here that moral teaching in the public schools should be wholly non-sectarian, and many believe it to be impossible to introduce the Bible into the schools without at the same time removing one of the strongest guards against sectarianism.”

In 1898 Utah, “non-sectarian” meant no Bibles. But in many eastern and southern states, non-sectarian had a much different meaning. Most eastern and southern respondents felt that if the Bible could be used in a way that did not discriminate against or among Protestants, Catholics, and Jews, it could be used freely. In spite of the eager evangelical tone of the New Jersey superintendent, most of those who approved of reading from the Bible in public schools agreed it must be done “without note or comment.” Most school Bible rules explicitly stated that the Bible’s words must be allowed to stand free of any imposed interpretation.

For example, Baltimore’s Bible rule, according to Cook’s report, specified that schools might use either the evangelical-friendly King James Version or the Catholic-friendly Douay version for their school readings. The rule in New York City specified,

No school shall be entitled to, or receive any portion of the school moneys, in which the religious doctrines or tenets of any particular Christian, or other religious sect, shall be taught, inculcated, or practiced; or in which any book or books containing compositions favorable or prejudicial to the particular doctrines or tents of any particular Christian or other religious sect, or which shall refuse to permit the visits and examinations provided for in this chapter. But nothing herein contained shall authorize the Board of Education to exclude the Holy Scriptures, without note or comment, or any selections therefrom from any of the schools provided for by this charter.”

In other words, most school leaders agreed there must be no sectarian books in schools. In Utah, that meant no Bibles. But in New York, it didn’t. In New York, and many other eastern and southern states, the Bible stood out as a uniquely powerful book, beyond all sectarian controversy. All people, the thinking went, could support the reading of the Bible in public schools, since it transcended all religious differences.

Such differences in New York City and Baltimore focused on Catholic/Protestant/Jewish disagreements about the nature and uses of the Bible. Those in Utah and Idaho implied LDS/mainstream Protestant disagreements. Reporting from North Carolina, State Superintendent of Public Instruction John L. Scarborough noted a different division. The Bible, Scarborough responded to the survey, transcended racial differences, with a “native population, white and black, the majority of whom and their leaders, love the old Book, and its doctrines and morals. God bless her people every one, and keep her in the old paths.”

Most of the survey respondents who wanted Bibles in their schools argued that the Bible ought to be read in public schools for fundamentally non-religious reasons. Though some, like New Jersey’s and North Carolina’s superintendents, might have personally agreed with the Protestant evangelical mission of the Chicago Bible women, most framed their arguments in terms of moral indoctrination. For instance, one school superintendent from Tennessee declared that the Bible was and must remain in Tennessee’s public schools. He did not say this would lead children to heaven, though. Instead, he insisted, “The Bible is our rock of public safety.” Such arguments in favor of Bible reading in public schools seemed to resonate strongly in late-nineteenth-century America. Cook summed up this patriotic morality by noting, “Even as all political parties of the United States honor our Flag and National Constitution, so should the people of every faith look to our Nation’s Bible for instruction in National righteousness.”

In Cook’s opinion, the Bible stood out as a unique moral guide. She argued not only that it should be used in America’s public schools, but that it was used in a vast majority of those schools. Yet her own evidence shows how complicated that use was. In many parts of the country, the Bible in 1898 was seen in a way very similar to the way it is seen today: as a divisive religious book. In states such as Utah, Idaho, and Montana, state superintendents responded that the use of the Bible in public schools would mean an un-American imposition of religion in public schools. In many other regions, however, the Bible seems to have been embraced as an appropriate non-sectarian—or better yet, super-sectarian—book for use in public schools.

Where it was used, however, it generally took its place as a generic moral guide. Most school leaders did not say they read from the Bible in order to lead children to heaven. Much more common was the argument that public schools must read the Bible in order to lead children out of the gutter and the prison.

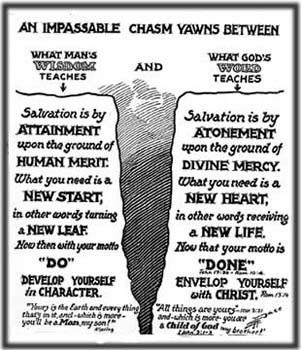

In 1560, Protestant divines completed an English-language Geneva edition of the Bible, flush with voluminous marginal commentary. According to historian Harry Stout, it would have been considered irresponsible by sixteenth-century Protestants to “provide this Word raw, with no interpretive guidance.” The commentary explained to readers, following Martin Luther, that every bit of Bible inclined toward the Christ.

In 1560, Protestant divines completed an English-language Geneva edition of the Bible, flush with voluminous marginal commentary. According to historian Harry Stout, it would have been considered irresponsible by sixteenth-century Protestants to “provide this Word raw, with no interpretive guidance.” The commentary explained to readers, following Martin Luther, that every bit of Bible inclined toward the Christ.