What do Phyllis Schlafly, Moses, and country/western music have in common? They all get happy shout-outs in new history textbooks in Texas. Or at least, that’s what conservative education leaders wanted. As Politico reported yesterday, new history textbooks in Texas are causing a stir. But this time, it is liberal activists, not conservative ones, who are denouncing the textbooks as biased and ideological.

The new textbooks were written to satisfy new standards approved years ago by the Texas State Board of Education. Back then, conservatives on the board, led by the genial Don McLeroy and the obstreperous Cynthia Dunbar, pushed through new standards that warmed the hearts of conservative activists.

No one who watched Scott Thurman’s great documentary about these Revisionaries can forget the moments when the SBOE debated including more country-western music and less hip hop. More positive statements about Reagan and the National Rifle Association. More happy talk about America’s Christian past and less insistence on the horrors of racial segregation.

As Don McLeroy said at the time, “America is a special place and we need to be sure we communicate that to our children. . . . The foundational principles of our country are very biblical…. That needs to come out in the textbooks.”

Now those changes in the Texas standards have shown up in new social-studies textbooks. As Stephanie Simons reports in Politico, liberals have complained that the new texts are woefully biased. In some spots, the books apparently knock Affirmative Action. They pooh-pooh the benefits of taxes. They imply that racial segregation was really not so bad.

For those who know the history of America’s educational culture wars, this seems like a drastic turnabout. Throughout the twentieth century, conservative school activists complained that they had been locked out of educational influence by a scheming leftist elite. Textbooks and standards, conservatives complained, had been taken over by pinheaded socialist intellectuals.

In one of the most dramatic school controversies of the twentieth century, for instance, conservative leaders lamented the sordid roots of new textbooks. That battle took place in Kanawha County, West Virginia, across the tumultuous school year 1974-1975. Conservatives were disgusted by the sex and violence embedded in new literature textbooks. But some of them weren’t surprised.

Conservative leader Elmer Fike told readers that the textbooks were bound to be rotten. In Fike’s opinion, conservatives didn’t even need to read the books. As he explained,

You don’t have to read the textbooks. If you’ve read anything that the radicals have been putting out in the last few years, that was what was in the textbooks.

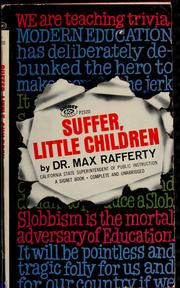

As the Kanawha County battle ground on, California’s conservative celebrity schoolman Max Rafferty came to town. Rafferty, too, told a crowd of West Virginians that they shouldn’t put any faith in textbook publishers. Those publishers, Rafferty explained, only wanted to make a buck. As he put it,

They have no particular desire to reform anybody, do anybody any good or find a pathway to heaven.

These days—in Texas at least—the shoe is on the other foot. The conservative standards that the state adopted in 2010 have pushed market-conscious textbook publishers to come up with books that meet them. And at least some conservatives are delighted with the success of their long game. As conservative school board member David Bradley told journalist Stephanie Simon, liberals who complain about biased textbooks can lump it. “They need to put on their big-girl panties,” Bradley crowed, “and go run for office.”