What do conservative activists hate about the Common Core State Standards?

A recent essay by conservative commentator Stanley Kurtz in National Review points out some conservative objections.

As we’ve noted recently, conservatives share with progressives a fervent opposition to the CCSS, though usually for different reasons. Everyone from Phyllis Schlafly to the Heritage Foundation has warned of looming implications for culture, politics, religion, and education. For those of us trying to understand conservative attitudes toward American education, these diatribes against the CCSS are a good place to start.

Kurtz was responding to an article in the Washington Post about Tea Party objections to the new shared standards. Obama officials, Kurtz complained, responded with deceptive statements and obfuscation. In the end, Kurtz argued,

. . . the Tea Party is right when it accuses the Obama administration of nationalizing education standards through the back door. The Founders opposed that for a reason. Once de facto nationalization is achieved, parents will lose their ability to influence their children’s education. Leverage that can be easily exercised at local school-board meetings or through representatives in state legislators will be lost to unaccountable federal bureaucrats (like Lois Lerner), and worse, to the even less accountable private education consortia that are developing the Common Core. So if educators try to impose politicized curricula or “fuzzy” math, parents will have no recourse.

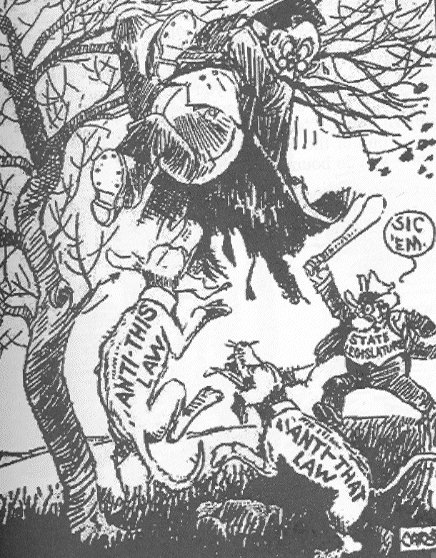

Kurtz’s “local control” argument echoes a long tradition among conservative education thinkers. Most powerfully, California State Superintendent of Schools Max Rafferty pushed hard during the 1960s to combat increasing federal control. Rafferty’s colorful prose often made the case more lyrically than I’ve seen it since.

In one speech from the archives,[1] Rafferty articulated a conservative position for local control that I suspect might still be appealing to today’s Tea Partiers. As he told the California Small School Districts Association Convention on March 8, 1965,

You live and work in an out-of-the-way corner of this county. A small town where the sky is still blue, where the roar and tension of freeway traffic has not yet penetrated; where a little boy can still run and play in open fields. You’re there because you want to be. You moved there deliberately a few years before because you liked that feeling of grassroots independence. That unique sense of having an equal share in the controlling of one’s own destiny which has been the legacy of every American ever since the first little villages began to dot the New England countryside more than three centuries ago. You’ve been happy there. Your children are growing up clear-eyed and self-reliant with that indescribable look of quiet confidence which comes from life spent in a region where hills and trees are very real, very close at hand. Where a neighbor is a lot more than someone who just happens to live close to you. Suddenly, something goes wrong at your local school house, as things sometimes do. Maybe it’s a new course of study which just doesn’t quite fill the bill. Maybe it’s a neurotic old school administrator, we do run across one now and then!

No matter, you tell yourself, nothing can possibly happen in your community which can’t be solved by you and your neighbors, working and acting together in the traditional American spirit of mutual tolerance and good will. But this time you’re wrong. Shockingly, unbelievably wrong! You and your friends try to arrange an appointment with your district superintendent to tell him of your problems and make your suggestions. But you don’t have a district superintendent anymore, in fact you don’t even have a district! You try to contact your local school board, but it’s gone too! A hundred miles away, a group of county or state officials meet once a month to decide the destiny of your children. You don’t know any of them personally, in fact you never even heard most of their names!

But in our nightmare today, they tell you what your children will be studying. They hire the teachers who will be molding the thinking and the behavior of your children throughout the years that lie ahead. They decide whether or not the school bus is going to stop near your home or indeed if there is going to be a school bus at all. Whatever they decide, you’re stuck with.

Rafferty worried about the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the direct progenitor of No Child Left Behind. As several of the commentators on Stanley Kurtz’s essay pointed out, the centralization of public schooling can be traced back through several generations of federal leaders, including President George W. Bush.

But that doesn’t mean that today’s version, the Common Core State Standards, will be greeted with anything but alarm among some sectors of conservative thought.

[1] This speech survives as a typescript in the Billy James Hargis Papers, University of Arkansas Mullins Library Special Collections, MC 1412, Box 48, Folder 2, Public Schools, 1950-1978 (1 of 2). This collection of papers represents, IMHO, the best single-stop shop for any scholar hoping to understand the career of twentieth-century educational conservatism. The Reverend Hargis was a leader in the Christian conservative movement in the second half of the twentieth century, and he was an avid collector of newsletters, correspondence collections, and other ephemera that shed a unique light on conservative thinking about education during the period.