Conspiracy sells. Just ask Dan Brown. But unwarranted anxiety about conspiracy also poisons our shared public life.

Conspiracy hunting used to be a sport dominated by conservatives. Think Joe McCarthy waving his sweaty lists of communist infiltrators. In recent years, though, politicians and commentators have found a new subversive threat: the Religious Right. A new book by former GOP functionary Mike Lofgren, for instance, warns of the ways his Republican Party was infiltrated and taken over by “stealthily fundamentalist” religious conservatives.

This kind of “paranoid style” has a long history in American public life. Witches were fiendishly difficult to detect in seventeenth-century New England. Scheming Catholics worried nineteenth-century WASPs. Communists emerged as the primary subversive threat in America’s twentieth century.

Leaders of the Religious Right have often worked up convincing conspiracies of their own. As historian William Trollinger has described, this tradition started with the first generation of American fundamentalists in the 1920s. One of the most prominent leaders of that Scopes generation, William Bell Riley, finally blamed evolutionary theory on a far-reaching plot of “Jewish Communists.”

In 1926, as I describe in my 1920s book (now in paperback!), one of the new grassroots fundamentalist organizations, the Bible Crusaders, announced the root of the evolution problem. “Thirty years ago,” the Bible Crusaders revealed,

“five men met in Boston and formed a conspiracy which we believe to be of German origin, to secretly and persistently work to overthrow the fundamentals of the Christian religion in this country.”

A generation later, writing in the magazine of Chicago’s Moody Bible Institute, one evangelical writer shared his experience with the famous progressive educator John Dewey. This writer told a cautionary tale of secularist conspiracy, with a story of Dewey’s eighty-fifth birthday party in 1944. Our evangelical witness had been invited to the celebration, the other guests unaware of his theological commitment. Celebrating the life of the prominent progressive educator, the guests proudly recalled their efforts to transform America’s schools from Christian institutions to secular training centers. “A generation has passed since that birthday gathering,” reported the evangelical spy to the MBI readership,

“and the plan has been immeasurably advanced by a series of court decisions that have de-theized the public schools. As a result, American state-supported schools are as officially secular and materialistic as are their counterparts in Communist countries. Are we awakening?”

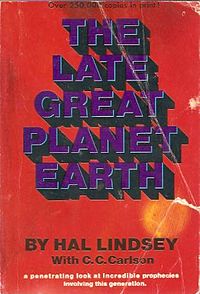

Such warnings shouted by Christian conservatives have occasionally attracted enormous audiences outside of religious circles. In the 1970s, Hal Lindsey’s Late Great Planet Earth became a runaway bestseller. With his co-author Carole Carlson, Lindsey spun a premillennial dispensationalist reading of the Bible into a riveting tale of international conspiracy. In the premillennial dispensational interpretation, popular among some conservative evangelical Protestants, the Antichrist will return in the guise of a savior, combining governments into a massive superstate. What seems like secular salvation is quickly revealed as the ultimate cosmic conspiracy, dedicated to binding all of humanity to a Satanic anti-religion.

These themes saw another burst of popularity in the late 1990s, when Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins repeated Lindsey’s feat. LaHaye’s and Jenkins’ Left Behind series fictionalized Lindsey’s tale, again turning a conspiratorial interpretation of the apocalypse into beach reading for millions of Americans.

These Christian conspiracies have not been without cultural cost. Though LaHaye and Jenkins carefully included a righteous Roman Catholic Pope among their fictionalized true Christians, other Christian conspiracy theorists, like William Bell Riley, have been too quick to implicate anyone outside of their circle of conservative evangelical Protestantism.

The dangers from conspiracy theorizing are not limited to the conspiracies imagined by conservative Christians. Overheated accusations about the threat from subversive groups have long posed a profound danger to our public life, as any blacklisted Hollywood writer or interned Japanese-American could attest. The threat is not limited to false conspiracies. Satan may not have inspired Salem’s witch troubles, but historian Ellen Schrecker has argued that the communist-hunters of the 1950s often targeted real communist conspirators, if in a clumsy and overly aggressive way.

Similarly, Lofgren’s ominous warnings are not spun of whole cloth. Lofgren warns vaguely of the “ties” of many leading Republican politicians to extreme positions such as Christian Dominionism. This theology, associated most closely with the late Rousas John Rushdoony, wants to establish Christian fundamentalist control over American political life. As Lofgren emphasizes, such thinkers approve the need to act “stealthily.”

Lofgren did not make this up. Dominionism exists. Prominent Republican politicians such as Rick Perry and Michele Bachmann really do work with groups who support such notions. But the way Lofgren and other commentators discuss such threats from the Christian Right distort the public discussion over the role of religion in the public sphere. As with warnings about President Obama’s connections to the “terrorist professor” Bill Ayers, this kind of conspiratorial rhetoric encourages a no-holds-barred approach to politics.

After all, as Lofgren intones, the “‘lying for Jesus’ strategy that fundamentalists often adopt” gives anti-fundamentalists a reason to punch below the belt in their culture-war battles. If they did not, the warning goes, they would be helpless before the wiles of the Christian Right. This is the primary danger of such breathless exposes as Lofgren’s. They build a shaky and fantastic argument upon a foundation of authentic examples in order to convince the convinced. Activists swallow the outlandish examples without demur. Such true believers do not consider the real complexities of their opponents, but rather paint a simplistic and terrifying image to shock and motivate their own side.

As with the real communist movement, the real world of American conservative Christianity is not such a simple place. Nor is it so headline-grabbingly power hungry. Consider a recent leadership poll by the National Association of Evangelicals. This organization, an umbrella group for conservative evangelical Protestants, asked just over one hundred of its leaders if the United States constituted a “Christian Nation.” Sixty-eight percent said no. One respondent told the NAE, “I hope others will learn to love Christ as I do, but that will happen more authentically through the Church and individual Christians sharing the Good News and demonstrating the person of Christ through our words and actions.”

This kind of statement from a conservative Christian does not sell books. What does sell is a cherry-picked catalog of statements by Christian leaders revealing their plans to take over American politics and public life. It was easy enough in Cold War America to discover evidence of a world-wide subversive communist movement. But as America learned from Senator McCarthy’s outlandish claims, there is a danger in stripping down the image of subversives to cartoonish bogeymen.

I am not a conservative Christian myself. I do not hope to apologize for the excesses of some conservative Christians. Indeed, I believe denunciations of the schemes of conservative Christians have some basis in fact. But when they serve only to encourage anti-fundamentalists to fight dirty, they do more harm than good. When such conspiracy-hunters ignore the complexities and ambiguities of their targets, they attack more than their real enemies. They smear innocent bystanders and poison the political life of the nation.

move to the New York Jets brought a new round of media focus on Tebow’s style of loud public Christian-ness.

move to the New York Jets brought a new round of media focus on Tebow’s style of loud public Christian-ness.