Fundamentalists don’t like progressive education. They may not realize that they have some potential allies deep in the heart of the academic education establishment.

What do fundamentalists mean when they fight against “progressive education?” For one thing, fundamentalists tend to pooh-pooh reading instruction that allows children to ‘discover’ reading on their own. And they dismiss the notion that classroom teachers should put authority in the hands of students. Also, fundamentalists often look askance at education professors who advocate soft-heading, child-centered classroom teaching that fails to deliver basic information and academic skills.

Generally, fundamentalists make these complaints from outside of the academy. Some historians and other prominent academics—folks such as Arthur Bestor, Robert Hutchins, or Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.—have critiqued the claims of progressive education, but most of the effective critics have worked outside of higher education. But in the past generation, at least one prominent academic educator has critiqued “advocates of any progressive movement” who fail to consider the opinions of those “who may not share their enthusiasm about so-called new, liberal, or progressive ideas.” The work of this world-famous educational activist is read at every school of education, especially ones in which teachers are trained to use progressive teaching methods.

Then why does she talk this way? Because she framed the issue not as traditional and progressive, but as black and white. Her name is Lisa Delpit, and her traditionalist critique of progressive education did not lead to her exclusion from the education academy. On the contrary, she has received some of the academy’s most prestigious awards for her work, including a MacArthur “Genius” award in 1990 and Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Outstanding Contribution to Education award in 1993.

To be clear, Delpit demonstrated considerable differences from many other traditionalist education activists. For example, she backs a multicultural approach to education, most conservative traditionalists do not. (See the ILYBYGTH discussion of traditionalist critiques of multicultural education here, here and here.) She supports reading in depth and excoriates rote instruction.

To be clear, Delpit demonstrated considerable differences from many other traditionalist education activists. For example, she backs a multicultural approach to education, most conservative traditionalists do not. (See the ILYBYGTH discussion of traditionalist critiques of multicultural education here, here and here.) She supports reading in depth and excoriates rote instruction.

But she also pushes a traditionalist ideology of teaching. She offers withering criticisms of progressive teachers’ justifications. In one career-making speech and article from the late 1980s, Delpit castigated progressive educators for their misplaced softness toward students. She cited with approval one African American classroom teacher who described her anger at white progressive teachers as “a cancer, a sore.” This teacher had stopped arguing against progressive methods. Instead, she “shut them [white progressive teachers and administrators] out. I go back to my own little cubby, my classroom, and I try to teach the way I know will work, no matter what those folk say.” Delpit suggested that a direct-instruction model matched more closely the cultural background of most African American students. In one model Delpit described favorably, the teacher is the authority. The goal is to teach reading via “direct instruction of phonics generalizations and blending.” The teacher keeps students’ attention by asking a series of questions, by eye contact, and by eliciting scripted group responses from the students. Such traditionalist pedagogy, Delpit noted, elicited howls of protest from “liberal educators.”

In a sentence that could come straight from such conservative traditionalist leaders as Bill Bennett or Max Rafferty, Delpit supported the notion of many African American educators that “many of the ‘progressive’ educational strategies imposed by liberals upon Black and poor children could only be based on a desire to ensure that the liberals’ children get sole access to the dwindling pool of American jobs.”

In another critique, Delpit argued that white, middle-class teachers hid their classroom authority in ways that were confusing to poor and African American students. Teachers of all backgrounds, Delpit suggested, need to be more explicit about their power and authority in the classroom. A good teacher, Delpit noted, was seen as both “fun” and “mean” by one African American student. Such a teacher, Delpit’s interviewee argued, “made us learn. . . . she was in charge of that class and she didn’t let anyone run her.”

More important for fundamentalist activists, Delpit’s voice is not alone. A call for traditional pedagogy and schooling seems to be gaining adherents among African American parents and educators. We could look at the deep traditionalism of such prominent schools as the New York Success Academy Charter Schools. Or we could probe the attitudes of those who run KIPP (Knowledge Is Power Program) Schools, which tend to serve significant numbers of African American students. In a recent article about school “paddling” in USA Today, one African American school administrator confirmed that she believed in spanking “because I’m from the old school.”

The numbers indicate African American students tend to receive corporal punishment more often than students of other racial backgrounds, but don’t indicate the level of support for such punishment among African American teachers as opposed to teachers of other races. There are some indications that African American parents tend to use corporal punishment more often than other groups. This would support Delpit’s assertion that many African American students have different cultural expectations from other students when they get to school. But the same study asserts that a huge majority of parents of other groups also use corporal punishment at home. And, indeed, there is a lot of support for corporal punishment at school among white conservative activists. But such support generally comes as part of a broader traditionalist, anti-progressive ideology of schooling.

Delpit’s argument is different. She argues for traditional authoritarian teachers within a progressive, multicultural educational system.

What does this mean? I’ve got a couple of reflections, and I’d welcome more.

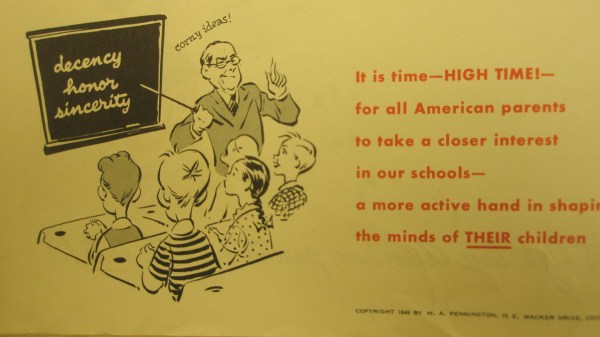

For one thing, it tells us something about the current state of education scholarship. Seen optimistically, we might conclude that the popularity of Delpit’s work proves that education scholars are willing to embrace a true diversity of opinion. That is, education scholars might not be the petty intellectual tyrants some traditionalists accuse them of being. To cite just one example, arch-traditionalist Max Rafferty in 1968 accused the “education bureaucrats” of only speaking to regular people “with that air of insufferable condescension.” Such “educationists,” Rafferty charged, only listened to one another; they only hoped to turn America’s schools into something approaching a “well-run ant hill, beehive or Hitlerian dictatorship.” Delpit’s example of progressive traditionalism might suggest that education scholars are more open to dissent than Rafferty and others have consistently charged.

In a less rosy light, though, we might conclude that this is yet another example of the ways the mainstream academy is hamstrung over racial ideology. We might wonder if Delpit’s ideas would be welcomed as fervently if education scholars weren’t so terrified of being considered racially insensitive. It helps, of course, that Delpit is a wonderful writer and powerful polemicist. But it is hard to ignore the question: How warmly would a scholar be welcomed who trashed the idea of progressive pedagogy in general? Not just for one group of students, but for students and schools in general?

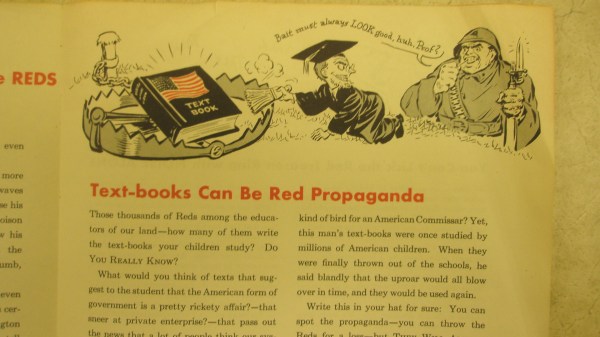

One other point jumps out at us: we apparently need to be more careful when we talk about traditionalist education. I’ll plead guilty. I am most interested in those traditionalists who act out of what we can fairly call a conservative impulse to transform American schools and society. Folks like Rousas Rushdoony, Max Rafferty, Sam Blumenfeld, Mel and Norma Gabler. Groups like the Daughters of the American Revolution and the American Legion. Activists from these groups have long believed that teaching must be made more traditional so that American society itself can reclaim some of its lost glory. But there are traditionalists like Delpit who hope that schools will transform school and society in a vastly different way.

Perhaps we need to treat “educational traditionalism” the way we treat “evangelicalism.” A lot of folks, scholars and normal people alike, tend to treat “evangelicalism” as if it were the sole domain of white, conservative folks such as Billy Graham and Jerry Falwell. But religious historians are also interested in other forms of evangelicalism. There have always been leftist evangelicals, for instance, as Raymond Haberski has recently noted. And, of course, there has always been a strong evangelical tradition among African Americans.

Perhaps the most important notion to think about here is that we have more than one kind of educational traditionalism. Bashing progressive education has long been the national pastime of educational conservatives. For the last twenty-five years or so, such conservatives have been joined by an influential cadre of mainstream education scholars.

Further reading: Lisa Delpit, “The Silenced Dialogue: Power and Pedagogy in Educating Other People’s Children,” Harvard Educational Review 58 (Fall 1988): 280-199; Delpit, (1986). Skills and other dilemmas of a progressive black educator. Harvard Educational Review, 56(4), 379-386; Delpit, Lisa. (1995). Other People’s Children: Cultural conflict in the classroom. New York, NY: The New Press; Delpit, L & Perry, T. (1998). The Real Ebonics Debate: Power, Language, and the Education of African-American Children (Eds.). Boston, MA: Beacon Press; Delpit, L. & Dowdy, J. K. (2002). The Skin That we Speak: Thoughts on language and culture in the classroom (Eds.). New York, NY: The New Press; Delpit, L. D. (2012). Multiplication is for White People: Raising expectations for other people’s children. New York:The New Press.