If you listened only to his press releases, you’d think creationist impresario Ken Ham was the most persecuted man in America, standing boldly in the path of “brainwashed” government leaders set on ruthless atheist indoctrination of America’s creationist kids. Mostly, his puffed-up rhetoric is silly and overblown. In one recent case, though, Ham and his colleagues are exactly right. There is no reason why they should not be allowed to engage in their peculiar science. More specifically, there is no reason why the government should not give them equal access to research materials.

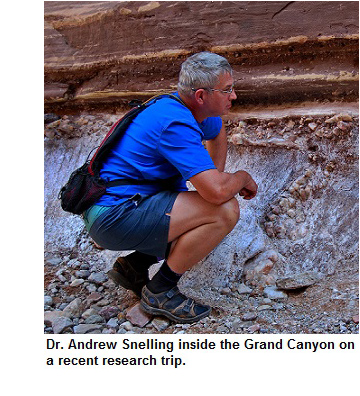

Here’s what we know: Andrew Snelling, a young-earth creationist researcher affiliated with Ham’s Answers in Genesis organization, has been denied permission to remove rocks from the Grand Canyon. Yesterday, the conservative activist organization Alliance Defending Freedom has filed suit on Snelling’s behalf in federal court.

The suit alleges that the Department of the Interior unfairly discriminated against Snelling for his creationist religious beliefs. Snelling had hoped to remove about thirty pounds of rocks from the Grand Canyon. He wanted to ship them back to his lab in Kentucky for research purposes.

According to news accounts, Dept. of Interior officials sent his application to mainstream scientists for review. One called Snelling’s creationist research “outlandish.” Another rejected the application due to its “dead-end creationist material.”

Let me be clear: I agree that the science pursued by Snelling is outlandish. It might not be “dead-end,” but it is “zombie science.”

But that does not mean that Dr. Snelling does not have every right to engage in his scientific pursuits. The reviewers in this case seem to have a woefully skewed idea of the proper role of government. According to one report, at least, one of the academic reviewers told the Department of Interior this case was

not a question of fairness to all points of view, but rather adherence to your narrowly defined institution mandate predicated in part on the fact that ours is a secular society as per our constitution.

Of course, that’s not what our First Amendment demands at all. Its two clauses—the establishment clause and the free exercise clause—never demand or even suggest a government role in creating a secular society. Rather, the federal government may not establish a religion. Nor may it inhibit free exercise of religion.

In this case, the government has no mandate to decide if Snelling’s work is secular enough to qualify. Neither the government nor anyone else can say with a straight face that Snelling is not engaged in scientific research. It might be kooky. It might be zombie. But “science” is not subject to a simple demarcation. It’s not a simple matter for anyone to rule something out of the realm of science. It is certainly more than government regulators can hope to do.

What should the Department of Interior do? Let Snelling sample the rocks! Give him equal access to publicly available research materials!

None of this means that the Department of the Interior can never limit the use of Grand Canyon rocks. Obviously, if some scheming entrepreneur wanted to take rocks out of the canyon to sell, he should be denied. Or, if the rocks were extremely rare and fragile—if removing them would harm the canyon—permission should be denied.

Plus, at times the federal government needs to make hard decisions about good science. When there’s federal money on the table, for instance, the government has a duty to choose the best, most promising proposals to fund. So, in this case, if Dr. Snelling was applying for a National Science Foundation grant to pay for his research, it would make perfect sense for reviewers to weigh in on the likely “dead-end” nature of his proposed research.

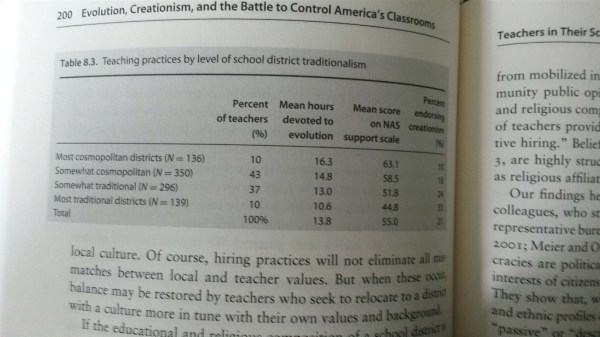

Similarly, if kids and public education are involved, the government has a similar duty to discern. As Harvey Siegel and I argue in our recent book Teaching Evolution in a Creation Nation, just because we can’t clearly define away creation science as non-science, we can still conclude that it is worse science. We don’t need to include every scientific idea in public-school science classes, only the good ones. And by any reasonable measure Dr. Snelling’s young-earth science is not as good as mainstream evolutionary science.

In this particular case, however, there is no government money on the table. There is no implied endorsement of religious ideas. There are no public schools involved.

So we say: Let Snelling work! Let him study rocks!

Of course, the folks at Answers In Genesis might not like some of the results. If they call for scientific resources to be open for all, they should also open up their one-of-a-kind fossil resources to outside researchers.