[Editor’s note: To SAGLRROILYBYGTH, Dr. Don McLeroy needs no introduction. As the genial conservative former head of the Texas State Board of Education, Dr. McLeroy is well known especially for his firm creationist beliefs. As I finish up my new book about American creationism, I reached out to Dr. McLeroy to ask him about his ideas. He graciously responded with an explanation and some questions of his own. He asked me, for instance, why I had so much confidence in mainstream evolutionary science. For the past few months, Dr. McLeroy and I have been reading key works together. He has explained to me why he finds some of Kenneth Miller’s work problematic and finds some convincing. I suggested a few of my favorite books, such as Edward Larson’s Evolution and Kostas Kampourakis’s Understanding Evolution. Dr. McLeroy read both and offered his explanation of why he found Dr. Kampourakis’s book ultimately unconvincing. I thought Dr. McLeroy’s critique of Understanding Evolution would be interesting to others, so I asked Dr. McLeroy for permission to publish it here. It appears below, unedited and unmodified by me.]

A critique of Kostas Kampourakis’ Understanding Evolution, Cambridge University Press, 2014

By Don McLeroy, donmcleroy@gmail.com

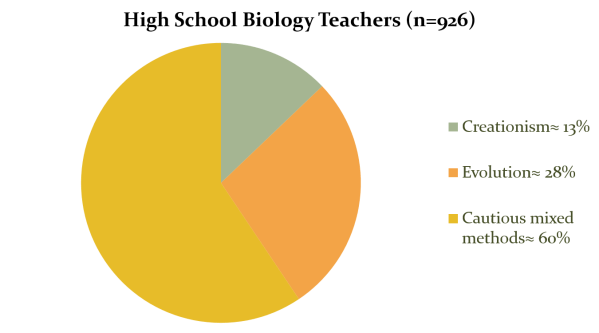

Kostas Kampourakis believes if you truly understand evolution—the idea that all life is descended from a common ancestor as a result of unguided natural processes—you will accept it and to this end he wrote his book. He does offer a unique contribution to the literature; besides an original discussion of “the core concepts of evolutionary theory and the features of evolutionary explanations,” (p. xi) he specifically concentrates on explaining why he believes evolution is hard to understand and why it has not won widespread acceptance. He emphasizes the conceptual obstacles to understanding evolution, how it is counter-intuitive and why there is so much religious resistance.

As for explaining the core concepts of evolution, his book succeeds; I do have a better understanding of evolution. However, I do not find his discussion of the conceptual difficulties of understanding evolution very compelling. The main obstacle for the evolution skeptic is the evidence doesn’t support it. And, if evolution is false, rejection of evolution is not counter-intuitive. However, he may be right; conceptual obstacles could play a major role in the evolution controversies. Only I think he has it totally backwards and the conceptual difficulties lie with the evolutionist inability to reject evolution.

Understanding core concepts

He devotes two chapters of his book to the core concepts of evolutionary theory: “Common ancestry” and “Evolutionary change.” They are unlike any other evolutionary explanations I have ever read. They are challenging, interesting and I enjoyed studying them. One reason is because Kampourakis has an excellent imagination and he uses it to create “imaginary” examples to help illustrate evolutionary ideas. He has imaginary beetles, imaginary families, an imaginary Gogonasus man, imaginary slides with rolling balls, imaginary “Jons and Nathans,” and an imaginary pizza shop evolving into an imaginary cookie shop. These examples do help in understanding evolutionary concepts, but I am left wondering, why not use actual examples to illustrate these ideas? Are simple real life examples unavailable to explain evolution?

Kampourakis’ book, like every other evolutionary apologetic book I have read, leaves me a stronger skeptic. The first thing I do when I read a new book on evolution is to look for any actual evidence cited that supports evolution. These books all claim they have lots of evidence, but when I read the books I do not find it. Kampourakis agrees the first requirement of a good scientific theory is the “empirical fit or support by data.” (p. 209) He claims “The fact that we do not know some details yet, as well as that we may never know all the details, does not undermine how strongly evolutionary theory is supported by empirical data.” (p. 209) Therefore, how many actual facts do we see included in this book? He presents some biology but not much evolutionary evidence. Interestingly, I find more imaginary examples than actual examples. His strongest example is Neil Shubin’s Tiktaalik.

The conceptual difficulties

The unique purpose of Kampourakis’ book is to focus “on conceptual difficulties and obstacles to understanding evolution.” (p. 62) I find it interesting his goal is not for everyone to “accept” evolution but simply to “understand” it. Again, he seems to believe if only we could understand it, then of course, we would accept it. I believe I do understand evolution. And, the more I understand it the more skeptical I have become. What amazes me is how many intelligent, educated people understand evolution and then accept it. Therefore, let’s examine the conceptual problem in reverse. The question would now be: What are the conceptual difficulties facing the evolutionist in ultimately rejecting evolution. I believe they are easily identifiable.

Not knowing they don’t have enough evidence

This brings us back to the key issue—the evidence. I believe the first and most significant conceptual obstacle in preventing the evolutionist from rejecting evolution is in not realizing how much evidence is needed to show evolution to be true. To illustrate, how much evidence has evolution presented to demonstrate how the myriads of biochemical pathways have supposedly developed naturally? Kampourakis’ book is completely silent on this issue. But, Kampourakis provides for more evidence for evolution by referencing a “Further reading” section at the end of his first chapter. Here he begins “There exist numerous books which present the evidence for evolution as well as the main processes. A nice book to start with is Jerry Coyne’s Why Evolution Is True, which provides an authoritative overview of evidence and processes. Another book with several examples and useful information is The Greatest Show on Earth: the Evidence for Evolution, by Richard Dawkins.” (p. 29) Therefore, based on Kampourakis suggestion, let us examine how well these two books explain the evolution of biochemical pathways.

In Dr. Coyne’s book, the only specific evidence he provides to demonstrate biochemical complexity is to hypothesize an imaginary common ancestor of sea cucumbers and vertebrates had a gene that was later co-opted in vertebrates as fibrinogen. (Coyne, ps. 131-3) Richard Dawkins presents even less evidence than Jerry Coyne. He describes the cell as “breathtakingly complicated;” stating “the key to understand how such complexity is put together is that it is all done locally, by small entities obeying local rules.” (Dawkins, p. 438) He also states some of the features of the cell descended from different bacteria, that built up their “chemical wizardries billions of years before.” (Dawkins, p. 377) These statements are not evidence. Click on the links associated with each picture to see what evolution must explain and decide for yourself how strong the evidence is for what Kampourakis’ experts present.

In conclusion, Kampourakis, Coyne and Dawkins do not seem to be concerned about the lack of evidence supporting the evolution of biochemical pathways. And, this is only one small area evolution encompasses that needs explaining.

Not knowing how many just-so stories they tell

The second conceptual block the evolutionist faces in rejecting evolution is they don’t seem to realize or be bothered by how much they depend upon just-so stories in their explanations for how evolution actually happened. Kampourakis, to his credit, doesn’t spin too many just-so stories; he simply presents them as facts. Examine this table Kampourakis includes in his book (p. 172). These transitions are presented as facts, as the truth. Here, the conceptual block the evolutionist faces is the failure to ask the key question “HOW did this happen?” For example, can evolution answer these questions for the first four transitions?

- HOW did repeating molecules arrive and HOW did these molecules become enclosed in a membrane?

- HOW did these molecules become coordinated as chromosomes?

- HOW did the RNA, DNA, and proteins develop protein synthesis and HOW did the genetic code information arrive?

- HOW did the eukaryote cell arrive? Does the concept of endosymbiosis deal with enough of the complexities involved to assume the problem is basically solved?

Not knowing the definition of science

Not knowing the definition of science

Finally, the most foundational conceptual obstacle preventing the evolutionist from rejecting evolution is they have defined themselves into a box. Kampourakis, after a lengthy and excellent discussion of religion and how it relates to science concludes “Science is a practice of methodological naturalism: Whether a realm of the supernatural exists or not, it cannot be studied by the rational tools of science. Science does not deny the supernatural, but accepts that it has nothing to say about it. Science is a method of studying nature, hence methodological naturalism.” (p. 59) But, what if God really did create life? This would mean Kampourakis’ science would not be able to discover it. I find this an untenable situation for science.

The solution, as I see it, is to reject “methodological naturalism” and endorse “The National Academy of Sciences” definition of science. In its book Science, Evolution, and Creationism, 2008, the National Academy defines science as: “The use of evidence to construct testable explanations and predictions of natural phenomena, as well as the knowledge generated through this process.” (p. 10) This wording is excellent: it supports both a naturalist and a supernaturalist view of science. With it, science must only limit itself to “testable explanations” not methodological naturalism’s “natural explanations.” Now, the supernaturalist will be as free as the naturalist to make testable explanations of natural phenomena. Let the view with the best empirical evidence prevail. Unfortunately, with Kampourakis’ purely naturalistic view, he and his fellow evolutionists are trapped in a box with only naturalistic explanations; they then must accept naturalistic evolution. As a Christian, I am free to accept or reject evolution. Kampourakis even documents leading Christian scientists who accept evolution by quoting Francisco Ayala and Kenneth Miller. (p. 46)

Conclusion

Kostas Kampourakis’ Understanding Evolution argues if you truly understand evolution you would come to accept it. For this to happen, he believes you just need to overcome conceptual obstacles standing in your way. I argue just the opposite; I believe if you truly understand evolution you will come to reject it. We agree though, for this to happen, you just need to overcome conceptual obstacles standing in your way.

Not knowing the definition of science

Not knowing the definition of science