[Warning: Explicit goose-related content.]

It’s not news. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and other tech-illionaires keep trying and failing to fix schools. The latest story from Connecticut gives us a few more clues about why these smartest-people-in-the-room can’t get it right. In the shocker of the year, it turns out parents don’t like having their kids read about people having sex with geese.

Will this be on the test?

It’s not the first time Zuckerberg has goofed when it comes to school reform. As SAGLRROILYBYGTH may recall, he has dropped the ball in Newark and with SAT prep classes. He has mistaken the right way to think about schools, repeating centuries-old errors.

What’s the latest? Parents in an affluent section of Connecticut have rebelled against a facebook-sponsored introduction of Summit’s “personalized” learning system. These sorts of systems promise that students will be able to work productively instead of marching at lockstep with the rest of the class. They hope to use technology to allow students and teachers to learn, instead of just sitting idly in classrooms.

In towns like Cheshire, Connecticut, the Summit system was run on free student computers, sponsored by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, facebook’s philanthropic arm. Students in middle school and elementary school would be able to work at their own pace toward clearly delineated learning goals.

It was gonna be great.

As New York Magazine reported, it didn’t work out that way:

the implementation over the next few months collapsed into a suburban disaster, playing out in school-board meetings and, of course, on facebook. The kids who hated the new program hated it, to the point of having breakdowns, while their parents became convinced Silicon Valley was trying to take over their classrooms.

What went wrong? As anyone who knows schools could tell you, the Summit/facebook folks made a fundamental error about the nature of schools. They forgot or never knew a couple of basic, non-negotiable requirements of real schools.

First, they fell into the start-up trap. Priscilla Chan of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative described her awe when she first saw a Summit-style school. As she gushed,

I walked into the school and I didn’t recognize where I was. . . . My question was like, ‘What is this? Where am I? Because this is what I see folks actually doing in the workplace: problem-solving on their own, applying what they’re learning in a way that’s meaningful in the real world.’

Like other techies, the facebook folks thought that schools could should look like tech companies, with maximum productivity and maximum independence. What they don’t seem to notice is that schools are not only open to those few nerds who like to work that way.

In Cheshire, teachers found that about a third of the students flourished in their new classrooms. But that left a vast majority of students floundering. As teachers do, they filled in the gaps. As New York Magazine describes,

The teachers started holding “Thursday Night Lights” sessions, where they’d stay until about 8 p.m., helping students rush through the playlists and take assessments while the information was fresh in their memories. To make up for the rest, he said, teachers found “workarounds,” like rounding up half-points in students’ grades, or coming up with reasons to excuse students from certain segments. (The other educators confirmed this.) “Looking back,” he said, “it was grade inflation, and it was cheating the system that we had spent the whole year trying to figure out and couldn’t make work.”

Maybe even more crucially, the facebook approached crashed in Cheshire because it failed to satisfy another absolute requirement of all schools. Viz., it failed to convince parents that it was keeping children safe.

First off, parents fretted about the ways facebook was selling data about their kids. Even if the company bent over backwards to be accommodating to parents’ concerns, no parents liked the idea of putting their children’s data on the market.

More dramatically in this case, the Summit approach doesn’t try to protect kids from the informational anarchy that the interwebs can provide. Instead of textbooks and other vetted classroom content, Summit mostly provides a set of links that students can follow to read content. In this case, that lead to some dramatic difficulties. In fact, the whole controversy in Connecticut might have blown over if one concerned parent hadn’t discovered what Summit students might be reading in class.

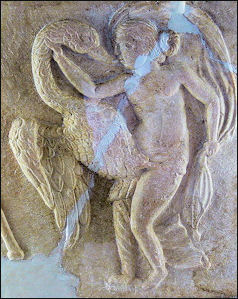

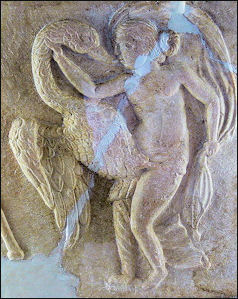

When the parent—Mike Ulicki—followed up on some social-studies links, he came across this page from factsanddetails.com. Yes, the page explained, ancient Romans had some pretty wild sexual habits, including sex with geese.

As anyone who knows anything about real schools could have told you, that was all it took.

As NYMag reported,

Ulicki posted the image on Facebook. As outraged comments multiplied on the thread, a school-board member announced he would call for a vote at the next meeting on whether to keep the program in place. But before the meeting could happen, they all received a letter from the superintendent’s office, announcing that Summit was being removed by executive order.

Now, honestly, any parent knows that their middle-schoolers could have found those kinds of images on their own. But for a school to be sending students to a picture of man-on-goose kink blew open one of the most foundational rules of schools. [There are other not-PG-13 images available at that site that I am too prudish to share. Interested readers can follow up here, though you might not want to do it at school.]

Schools are not only about giving students information. They are not only about preparing students to be life-long learners. They are not only about math, history, English, or science. Above all, schools must promise to keep students safe. Safe from physical threats, of course, but also safe from intellectual dangers such as the wild sexual practices of ancient Rome.

Until facebook’s founders and other would-be tech saviors recognize the way schools really work, they’ll never be able to deliver on their reform promises.