How do we start? What about students? …and isn’t it cheating to sneak in a definition after I say I’m not going to impose a definition?

They’ll bite!

Those were some of the smart and tough questions leveled at your humble editor last night after my talk at the University of Florida’s College of Education research symposium. The edu-Gators (ha) were a wonderful group of scholars to talk with. I got a chance to hear about their work in schools and archives, then I got to run my mouth a little bit about the culture-war questions that keep me up at night.

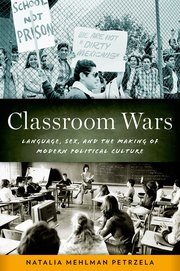

The theme of the symposium was “Strengthening Dialogue through Diverse Perspectives.” Accordingly, I targeted my talk at the difficult challenge of talking to people with whom we really disagree. I shared my story about dealing with a conservative mom who didn’t like the way I was teaching. Then I told some of the stories from the history of educational conservative activism from my recent research.

The UF crew…

What has defined “conservative” activism in school and education? Even though there isn’t a single, all-inclusive simple definition of conservatism—any more than there is one for “progressivism” or “democracy”—we can identify themes that have animated conservative activists. Conservatives have fought for ideas such as order, tradition, capitalism, and morality. They have insisted that schools must be first and foremost places in which students learn useful information and have their religion and patriotic ideals reinforced.

Underlying those explicit goals, however, conservatives have also shared some unspoken assumptions about school and culture. Time and time again, we hear conservatives lamenting the fact that they have been locked out of the real decisions about schooling. Distant experts—often from elite colleges and New York City—have dictated the content of schools, conservatives have believed. And those experts have been not just mistaken, but dangerously mistaken. The types of schooling associated with progressive education have been both disastrously ineffective and duplicitously subversive, conservatives have believed.

That was my pitch, anyway. And the audience was wonderful. They poked the argument (politely!) to see if it would really hold. One student asked a tough question: Given all this history, all this poisoning of our dialogue between conservatives, progressives, and other, how do we start? A second student followed up with another humdinger: I talked about conservative parents and school board members and leaders, but what about students? What should a teacher do if she finds herself confronted with a student who has a totally different vision of what good education should look like? Last but not least, a sharp-eyed ed professor wondered if I wasn’t doing exactly what I promised I wouldn’t do: Impose a definition on “conservatism” by offering a list of defining ideas and attitudes.

How did I handle them?

Well, SAGLRROILYBYGTH, your humble editor did his best, but those are really tough ones. In general, I think the way to begin conversations with people with whom we have very strong disagreements is to start by looking at ourselves. Are we making assumptions about that person based on things he or she isn’t actually saying? Are we seeing them through our own distorted culture-war lenses?

And if students in class disagree with us about these sorts of culture-war principles, we need to remember first and foremost that they are our students. If a student in my class, for example, is super pro-Trump, I want her to know first and foremost that I welcome her in my class and she is a member of our learning community. It gets tricky, though, if a student wants to exclude other students based on these sorts of religious and ideological beliefs.

Last but certainly not least, I don’t think it’s unfair to offer themes and ideas that have defined conservatism over the years. I’d never want to impose those definitions on historical actors, Procrustes-style. But once we take the time to listen and learn to our subjects, we can and should suggest some things that they have had in common.

On to breakfast with graduate students and a chance to participate in Dr. Terzian’s schools, society and culture colloquium. Bring on the coffee!