Top ILYBYGTH-themed stories from the past week:

Wait…what? Can Trump eliminate birthright citizenship? HNN collected historians’ comments.

- E.g. Martha Jones on the history of birthright citizenship at The Atlantic.

How have textbooks portrayed climate change? At TC.

It’s not college that frightens conservatives, it’s just the wrong type of college–a conservative plea for more evangelical colleges, at NR.

If anything, we should be sending more students to college — opening up further avenues of funding, both public and private, even as we pursue policies that might lower tuition or challenge the progressive domination of our campuses. Colleges will have to change, to be sure, but in the meantime conservatives would be wise not only to celebrate but to actively advance the interests of those institutions that are educating students properly right now.

Diversity training is good, says Eboo Patel at CHE. But why doesn’t it include religion?

What’s the deal with “messianic Judaism?” Neil J. Young describes the unique meanings at HuffPost.

When did evangelicals get involved in politics? Clyde Haberman tells the old myth about the 1970s at NYT.

- What’s wrong with that story? It’s just not true. Here at ILYBYGTH.

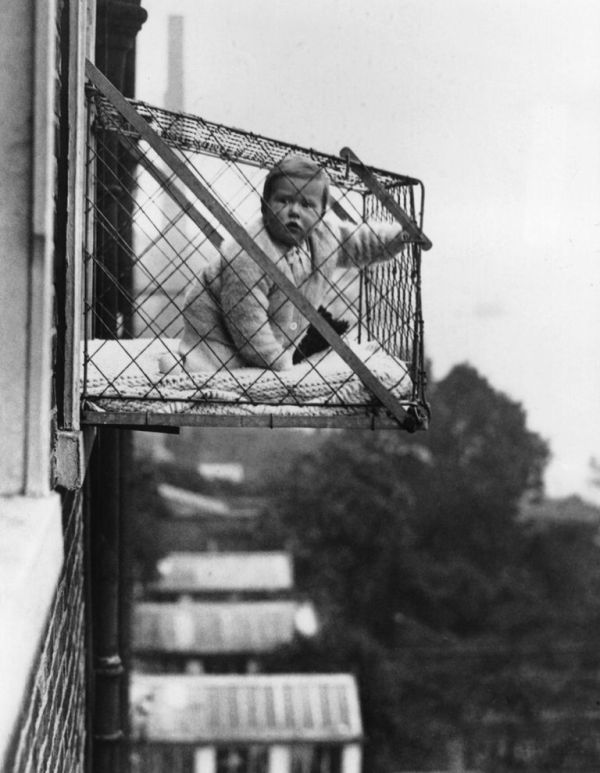

The new digital divide, at NYT.

It could happen that the children of poorer and middle-class parents will be raised by screens, while the children of Silicon Valley’s elite will be going back to wooden toys and the luxury of human interaction.

Atheism in America: A review essay in the New Yorker.

The radical-creationist view on climate change: It’s not a shame, it’s not a crisis…it’s a sin, at AIG.

How many people really believe in a flat earth? NCSE’s Glenn Branch takes another whack at the poll numbers, at SA.

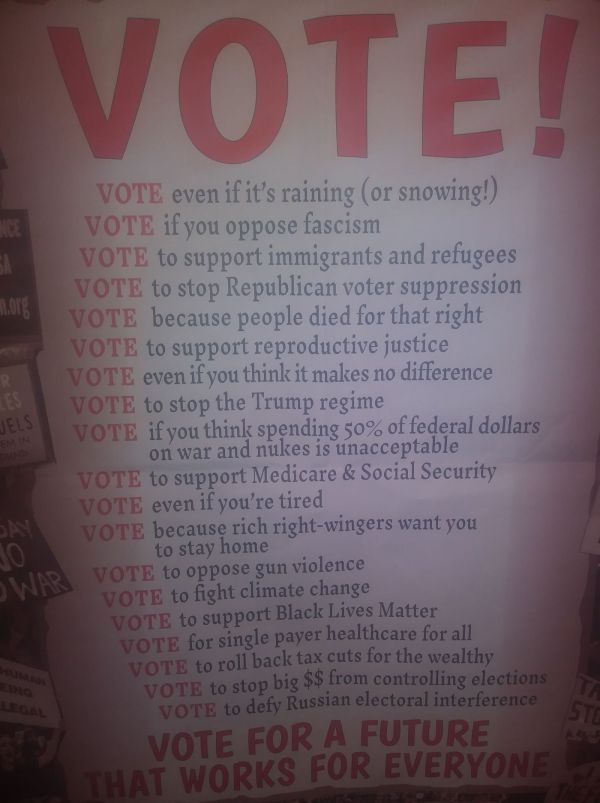

Class war or culture war? The divide in the Democratic Party, at Politico.

Ocasio-Cortez, the young Latina who proudly identifies as a democratic socialist, hadn’t been all but vaulted into Congress by the party’s diversity, or a blue-collar base looking to even the playing field. She won because she had galvanized the college-educated gentrifiers who are displacing those people. . . . Energized liberals, largely college-educated or beyond, have been voting in a new breed of activist Democrat—and voting out more established candidates with strong support among the party’s largely minority, immigrant, Hispanic, African-American and non-college-educated base.

- When it comes to schools, rich progressives have always balked at any change that threatens their status. Here at ILYBYGTH.

Have schools become a “Constitution-free zone?” Interview with Justin Driver at Slate.

Academia as a cult at WaPo. HT: MM.

Texas school board

Texas school board