Welcome to the latest edition of Fundamentalist U & Me, our occasional series of memory and reflection from people who attended evangelical colleges and universities. [Click here to see all the entries.] The history I recounted in Fundamentalist U only told one part of the complicated story of evangelical higher education. Depending on the person, the school, and the decade, going to an evangelical college has been very different for different people. This time, we are talking with Justin Lonas. Justin is an editor and content developer for a non-profit organization near Chattanooga, Tenn. He is also working on an M.Div degree at an evangelical seminary in Atlanta.

This time, we are talking with Justin Lonas. Justin is an editor and content developer for a non-profit organization near Chattanooga, Tenn. He is also working on an M.Div degree at an evangelical seminary in Atlanta.

ILYBYGTH: When and where did you attend your evangelical institutions?

From 2002-2006, I attended Bryan College in Dayton, Tenn., graduating summa cum laude. I majored in communications (journalism emphasis) with minors in history and Spanish.

ILYBYGTH: How did you decide on that school? What were your other options? Did your family pressure you to go to an evangelical college?

I first heard about Bryan when I was 16 through a speaker at a homeschool convention in North Carolina who was on their faculty. His thoughtful engagement with cultural issues intrigued me, so I added the school to my mental list. After visiting Bryan about a year later, I felt like it would be a good place to pursue—it was small (a very attractive point to someone who grew up in a crowded university town), and the students and faculty I met seemed very down-to-earth. Moreover, it was 4 hours from home so I could enjoy not having to go home all the time without quite fully “rebelling” by choosing a college on the other side of the country.

The other schools I considered were a mix of small-to-mid sized evangelical schools and public universities. Though I didn’t want to go to my hometown school (Appalachian State University), the other schools I seriously considered were all in NC: Mars Hill College (where I was offered a scholarship to study botany), Gardner-Webb University, and UNC (Chapel Hill).

As to family pressure, growing up in an evangelical family, and being educated both in private Christian schools and homeschooling, going to an evangelical college was, if not expected, at least not a surprise for me. Both my parents went to a state school and had found good Christian community through campus ministry groups, so they weren’t dead-set on any particular school for me. The only thing that I always felt was non-negotiable was that I go to college and do well. Where was secondary.

ILYBYGTH: Do you think your college experience deepened your faith? Do you still feel connected to your alma mater? What was the most powerful religious part of your college experience?

On balance, yes, my Christian faith was strengthened during my time at Bryan. The semi-compulsory chapel times were usually interesting, with many gifted outside speakers and often student-led music. The school’s baseline curriculum forced me to study the Bible at a deeper level than Sunday school, which I found fascinating. I was also able to connect with a local church in a nearby city (Chattanooga) that I actually joined and continued to attend for many years post-college as well. Many of the friendships forged on campus have lasted to the present, and though there were plenty of typical college shenanigans among us, there were also plenty of deep conversations about life and faith. Faculty routinely ate meals in the dining hall with students, and hosted students at their homes, seeing opportunities for spiritual discipleship as an extension of their educational mission.

Probably the most powerful religious aspect of my years at Bryan was not so much any particular high point as the consistency with which I saw Christian faith lived out by students and faculty alike (with plenty of exceptions, to be sure—including some pretty massive moral failures).

Connection to the school is a bit of a different question. On many levels, yes, I do feel very connected. Friendships with classmates and current and former faculty are still very much a part of my life, but I feel no particular connection to the school itself as an institution. I live just 40 minutes down the road, and I’ve been back to campus maybe 5 times in the past 13+ years. A large part of this has to do with some of the very public recent failings of the school (as referenced in the epilogue of Fundamentalist U). [Editor’s note: also discussed in these pages. See here or here.]

ILYBYGTH: Would you/did you send your kids to an evangelical college? If so, why, and if not, why not?

It’s an open question. My wife & I have four daughters, the oldest of whom is still a few years out from college, so I’d like to think I’d be willing to trust their judgment on which school is the best fit for them and the path they’re embarking on for life, career, etc. At the very least, I’d probably offer some strong cautions about any school they chose, as I don’t think you can ensure life outcomes through institutional structures—i.e. I don’t expect a school to do the work of the Holy Spirit in keeping them in the faith. I do think we’d be OK if they chose a Christian college, but these days, I’d feel better about a denominationally affiliated school with transparency and oversight than about an independent evangelical college. I’ve seen from Bryan in recent years how easy it is for an administration to gaslight people and become autocratic (even co-opting the board of trustees) without a much larger web of accountability at play.

ILYBYGTH: Do you still support your alma mater, financially or otherwise? If so, how and why, and if not, why not?

Neither my wife (who is also an alum) nor I have never financially supported Bryan College beyond one small gift to a regional scholarship fund some years ago. We both have felt for years (even during our time as students) that the current administration of the school was untrustworthy, and have had no confidence that any gifts would be spent wisely. We have also counseled friends away from sending their children to Bryan (in spite of some good things still going on there in several departments). We might be inclined to support the school in the future, if changes are made to how it is run. Time will tell.

ILYBYGTH: If you’ve had experience in both evangelical and non-evangelical institutions of higher education, what have you found to be the biggest differences? The biggest similarities?

I’m a “lifer” in evangelical schools, I suppose. I do get to spend a lot of time with the faculty and administration of a denominationally accountable college now because of my job, and there are important distinctions there. The chief difference seems to be the level at which faculty are given academic freedom and encouraged to go deep into their disciplines with excellence rather than threatened when they don’t tow the party line.

On balance, campus life is culturally very similar to Bryan, and certainly when compared to a secular college.

ILYBYGTH: If you studied science at your evangelical college, did you feel like it was particularly “Christian?” How so? Did you wonder at the time if it was similar to what you might learn at a non-evangelical college? Have you wondered since?

I only took a couple of science classes during my time at Bryan (since I was in a B. A. humanities track). The botany class I took was very straightforward, proceeding in much the same way as I’d expect a similar introductory class to go anywhere, with the exception of a devotional at the beginning of each class. The professor (who is still a personal friend) really emphasized the historic role of wonder and religious awe in driving scientific inquiry, quoting people like Newton and Kepler, and reading George Herbert’s poetry.

I did also take a non-lab science course on physical origins—i.e. the origin of the material world—from Kurt Wise. Dr. Wise was no intellectual slouch, having earned a Ph.D. in paleontology at Harvard under Stephen Jay Gould, but was firmly a young earth creationist. In that course, though, he taught the first seven weeks from a materialist perspective, refusing to admit any religious or biblical arguments, and focusing on evidence and mainstream scientific theory. In the second half of the course, he made a case, based on his own work, for how the evidence could be read in such a way as to affirm a literal reading of the Genesis narrative. It was fascinating, really.

It is telling that both science professors I had left the school under the current administration, which has used an accusation of unfaithfulness to literal young-earth creationism as a pretext to purge several faculty. I suppose that even teaching alternate perspectives for the sake of intellectual honesty and ensuring students were well-informed was a bridge too far. I do feel, though, that the scientific education offered at Bryan was quite solid, given that several classmates who majored in sciences have gone on to become doctors or work at research institutions like the WHO and the CDC.

ILYBYGTH: Was your social life at your evangelical college similar to the college stereotype (partying, “hooking up,” drinking, etc.) we see in mainstream media? If not, how was it different? Do you think your social experience would have been much different if you went to a secular institution?

Social life was generally bounded by a Christian ethos—a fact which I’m actually quite grateful. Sex outside of marriage was very taboo, but dating couples weren’t required to be chaperoned. Public displays of foul language, drinking, smoking, drugs, etc. weren’t seen (though you could find them in private). Friends and I spent plenty of time camping, hiking, and rock climbing at a local wilderness with lax campus “sign-out” policies and late curfew. I never felt like someone was watching me to ensure compliance with social life standards. Most of our free time was spent in recreation—card games, fishing, intramural sports, etc.—but the school was academically rigorous, so free time was limited if you wanted good grades. It was a small place, where everyone knew everyone, so community accountability more than anything else served to enforce standards. About the most transgressive things I did was going out to smoke cigars in the shadow of a nearby nuclear power plant (which seemed, I guess, like a safe place) and partaking in the god-awful “wine” a hallmate made from Welch’s grape juice.

ILYBYGTH: In your experience, was the “Christian” part of your college experience a prominent part? In other words, would someone from a secular college notice differences right away if she or he visited your school?

Bryan was unmistakably a Christian school. There was a 50 ft. tall cross at the top of the entrance road, for one thing. The rhythms of church and chapel punctuated student life, and every class had some tie-in to faith. Nobody would’ve mistaken it for a secular school.

Ironically, one of the craziest run-ins I had with administrative autocracy while a student was the school’s attempt to change its motto from “Christ above all” to “faithful brilliance.” Our student newspaper (where I was an editor) ripped the administration over the issue, and helped spark an alumni backlash against the shift. This was one of many instances that helped convince me that the school’s president cared more about authority than any actual issues of “defending the faith.”

ILYBYGTH: Did you feel political pressure at school? That is, did you feel like the school environment tipped in a politically conservative direction? Did you feel free to form your own opinions about the news? Were you encouraged or discouraged from doing so?

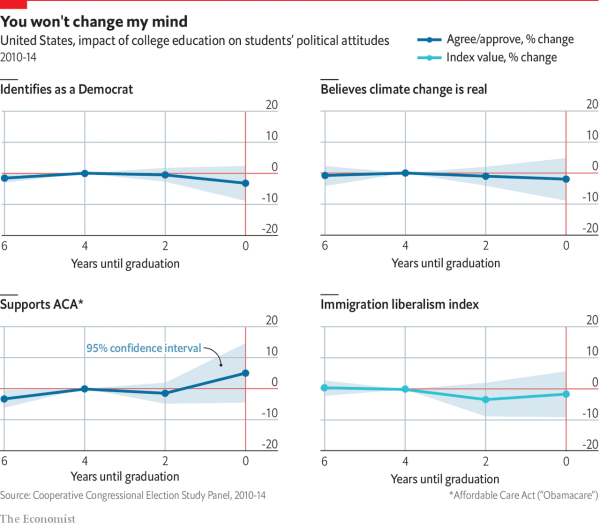

There was definitely political pressure at school, but far more of it came from fellow students than faculty or administrators. There was a definite sense that God must be a Republican, and it was hard to imagine how anyone could be anything other than pro-life and anti-same-sex marriage. Capitalism was in vogue, too. It was also the heady post-9/11 and Iraq War days, so there was a strong pro-military vibe going around, and a busload of students volunteered to go canvas for Bush in Florida during the 2004 election. If anything, several faculty tried to be moderating influences on rampant student conservatism, hoping to get us to widen our lenses a bit. I did not try very hard to form my own political opinions, and when I did (considering the legacy of racism in evangelicalism and conservative politics, for instance) I found ready encouragement from faculty. These days, I’d consider myself much more politically liberal than my collegiate self, not because I’ve drifted from my faith, but precisely because I’ve gone deeper into studying and applying the teachings of Scripture (particularly around care for the poor).

ILYBYGTH: What do you think the future holds for evangelical higher education? What are the main problems looming for evangelical schools? What advantages do they have over other types of colleges?

The future of higher education in general in the U.S. seems to be in doubt. Student loans have been a crushing weight on so many of my friends that many of us have openly considered whether college is worth it, and shared that we’d be perfectly happy if our kids went into a trade or other career that didn’t require a degree. Evangelical schools aren’t immune to these general pressures, either.

In addition to these general problems, I think a whole generation of Christians (and people of other or no religion who were raised Christian) have soured greatly on evangelical institutions due to repeated scandals of sexual abuse and coverups, financial malfeasance, and other legal problems. We see “leaders” supporting a manifestly corrupt and immoral president like Donald Trump at the expense of Christian witness to people in the rest of the world, and the whole edifice of evangelicalism starts seems like a fig leaf for power worship and egotism. If evangelical schools are going to survive by attracting the children of this generation to attend, it will be because they are able to cultivate an atmosphere of intellectual honesty and academic freedom within a culture gone crazy. When they feel like just so much more tribalism and cult-like authoritarianism, what’s the point?

If there is any advantage to evangelical schools over other colleges, it directly correlates to their willingness to be open and honest. Even secular schools have their ideological shibboleths and inquisitions, so evangelical colleges that are confident enough in their faith to assume that it is not the school’s responsibility to force social and spiritual outcomes may be able to rejuvenate the whole enterprise of higher ed. This hope is on an ideal plane, though. Most evangelical schools are in no wise prepared to pursue that vision.

Thanks, Mr. Lonas!

Did YOU attend an evangelical college? Are you willing to share your experiences? If so, please get in touch with the ILYBYGTH editorial desk at alaats@binghamton.edu

This move is not a new one for Trump. SAGLRROILYBYGTH will recall he made similarly meaningless promises to defend the use of the Bible in public schools. In his announcement yesterday, Trump declared,

This move is not a new one for Trump. SAGLRROILYBYGTH will recall he made similarly meaningless promises to defend the use of the Bible in public schools. In his announcement yesterday, Trump declared,