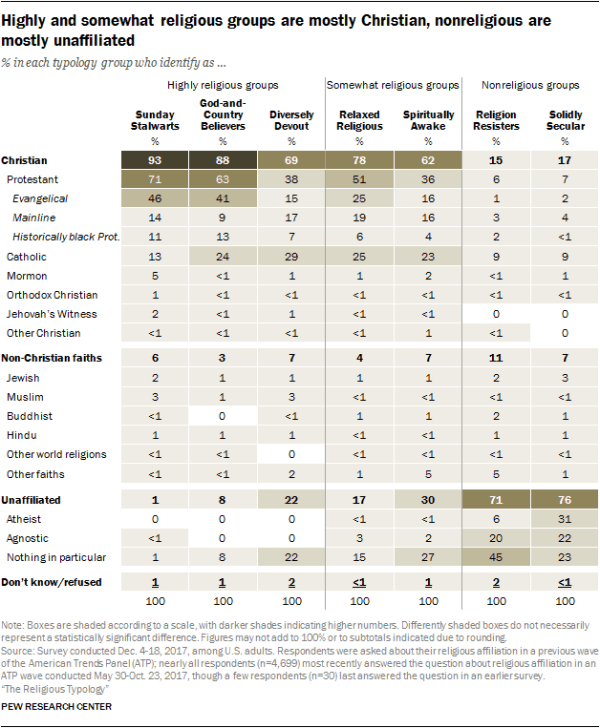

We all know it doesn’t help much to know someone’s religion. That is, just knowing that someone is Catholic, or Jewish, or Muslim, or Protestant doesn’t really tell us much about them. We want to know what KIND of Protestant someone is, what KIND of religious person. The folks at Pew have taken a stab at a new way of grouping religious people. Instead of denominations, sects, or faiths, Pew offers new “typologies.” Do they help you understand American religious and culture better? And do they confirm Professor Hunter’s twenty-five-(plus!)-year-old prediction?

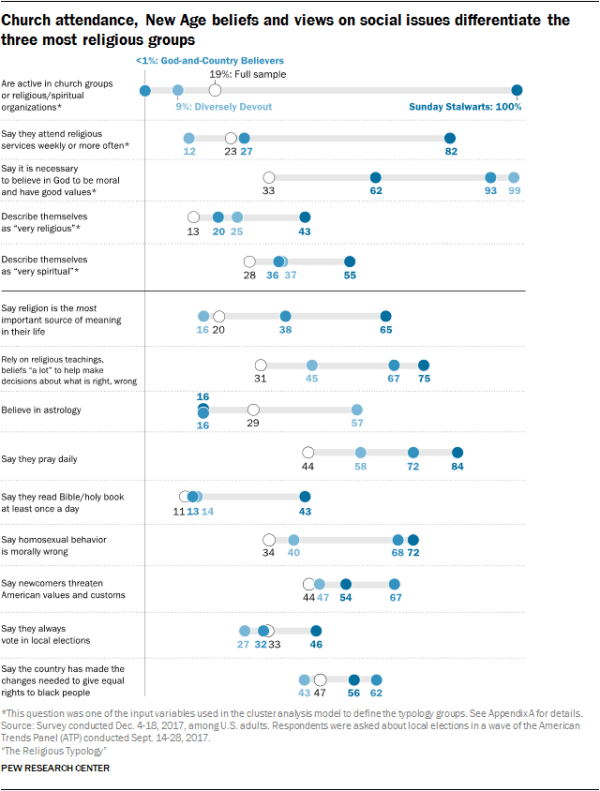

Here’s what we know: The typologies cluster Americans into three categories and seven groups. Some people are “highly” religious, others are “somewhat” religious, and the rest are “non-religious.” The highly religious folks are subdivided into “Sunday Stalwarts,” “God-and-Country,” and “Diversely Devout.” The somewhats are broken down into “Relaxed Religious” and “Spiritually Awake.” The non-religious are cut up into “Religion Resisters” and the “Solidly Secular.”

In some ways, these categories point out surprising facts. For example, as Friendly Atheist Hemant Mehta pointed out, the Solidly Secular are surprisingly similar to the stereotype of the GOP: Richer, whiter, and maler than the American average.

In other cases, the categories seem to confirm culture-war stereotypes. As the report notes,

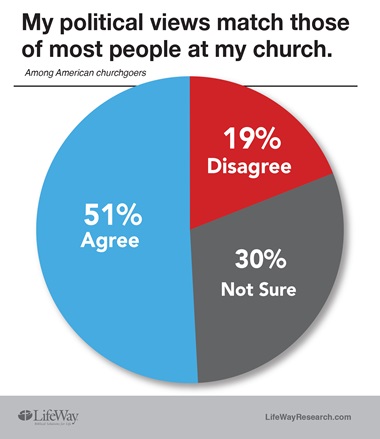

Although no political measures were used to create the typology, arraying the groups from most to least religious also effectively sorts Americans by party identification and political ideology. Republicans make up a majority of Sunday Stalwarts and God-and-Country Believers, while even larger majorities of Democrats comprise the two nonreligious groups. Similarly, self-described conservatives prevail among the two most religious groups, while, by comparison, the two nonreligious groups lean left.

Certainly, when we look at the three “highly” religious typologies, they seem to tilt hard to the cultural right. For example, they are more likely than average to think homosexuality is morally wrong. They are more likely to be leery of immigrants. And the Sunday Stalwarts and God-and-Country folks are more likely to think racial inequalities are a thing of the past.

To my mind, these typologies are much more useful than traditional labels such as “evangelical.” Lots of self-identified evangelicals, for example, cluster in the Sunday Stalwart, God-and-Country, and Diversely Devout types. But there are also plenty of evangelicals who are more “relaxed” about their faiths.

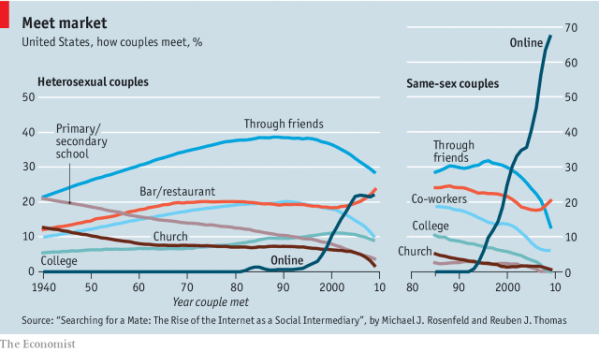

In part, these types seem to confirm what sociologist James Davison Hunter predicted back in the early 1990s. His claim at the time was that traditional religious labels would become less and less important. It would matter less and less, Professor Hunter argued, if someone was Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, or Muslim. Instead, people would tend to cluster around the culture-war poles, either “orthodox” or “progressive.”

Does it work for you? Do you feel these types are more useful than traditional labels to understand religious and cultural life in America? Do you fit into one of these typologies, or do they seem too simplistic?