Want to understand evangelical higher education these days? Then you need to read the recent exposé of Liberty University’s online program in the New York Times. But when you do, remember that they left out a central piece of the picture.

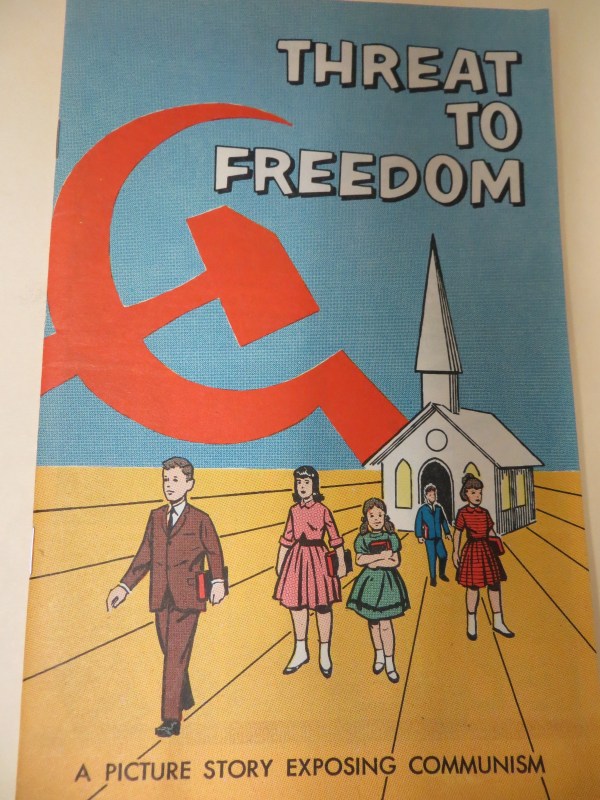

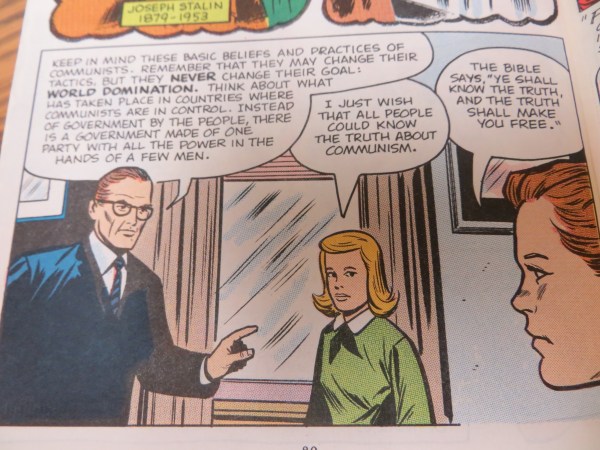

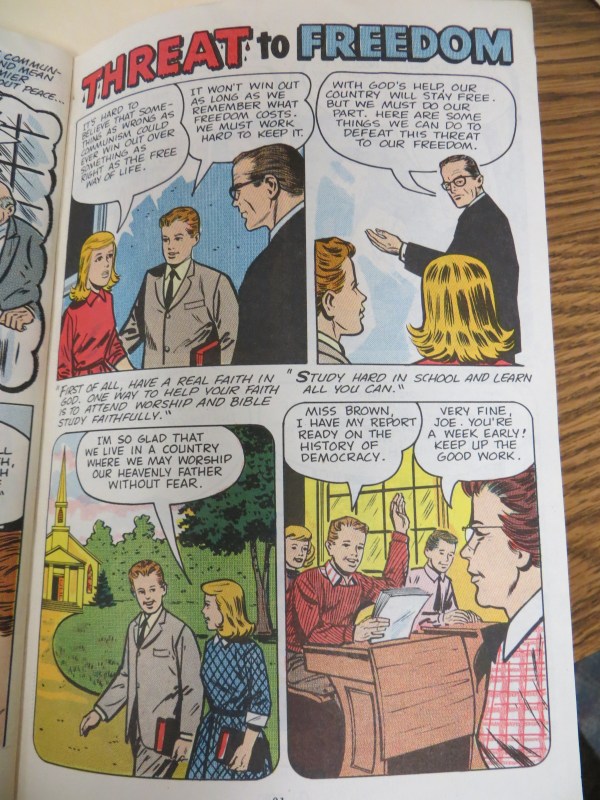

Early distance-learning programs at MBI claimed to reach the world with cutting-edge technology, c. 1947. These “mountaineers” got free Gospels if they read them in school. And, yes, that is their school building.

The Liberty Online story is a big one. As the Times article describes, Liberty now claims $2.5 billion (yes, that’s B-illion with a B) in net assets, largely from its online department. Because Liberty is a non-profit, it is not subject to the same oversight as for-profit schools such as Corinthian and the University of Phoenix.

Some online students, the article describes, felt pressured to sign up and ripped off with the results. As one unhappy former Liberty student told the Times,

What’s killing me is that I went into this program to try to change my situation . . . and I’m worse off than I was at the beginning.

It’s an ugly story. There is no doubt that Liberty’s online program has been a cash cow. As we’ve noted here at ILYBYGTH, there’s also no doubt that Liberty’s Jerry Falwell Jr. has plowed his online profits back into the brick-and-mortar campus. Sports, star faculty, and campus facilities all get plenty of funding. Recently, the Liberty football squad used that money to fulfill one of the school’s long-standing dreams by defeating top-ranked Baylor.

But the Times story leaves out a crucial part of the historical context. The way they put it, Liberty’s online program came about as part of an experiment, an “educational novelty.” As the article explains,

One educational novelty that Falwell dabbled in, starting in the mid-’70s, was an early form of distance learning. Liberty would mail lecture videotapes and course packets to paying customers around the country — at first just certificate courses in Bible studies, and by the mid-’80s, accredited courses in other subjects as well.

The inspiration, according to the NYT, was the work of John Sperling and the University of Phoenix. I don’t doubt that President Falwell Jr. admired Sperling’s business model. I don’t dismiss the importance of the notion that Falwell has treated his school, as he told NYT, “like a business.”

However, if we really want to understand Liberty’s online success, we have to also understand its context as part of the history of evangelical higher education. It is difficult for some secular people (like me) to notice or acknowledge, but evangelical schools and missionary institutions have always led the way with finding new ways to use new technology to deliver distance education.

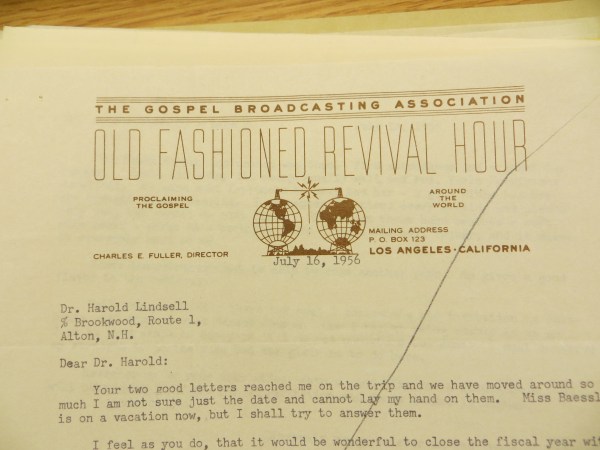

Check out the 1950s-era “high-tech” logo! More evidence of the evangelical obsession with technology and distance learning, from Fuller Seminary, c. 1956.

Perhaps the best example might be the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. No matter the decade, no matter the technology, the Moody educational empire has found ways to expand its reach using new technological means. The drive is obvious: For MBI and other evangelical institutions, the primary goal is to deliver the Gospel to as many human eyes and ears as possible, as fast as possible. If new technology will help accomplish that mission, all the better.

To note just a few of the best-known programs, MBI was a pioneer in early radio, with its WMBI established in 1926 to bring the Word to the world. By 1940, WMBI’s Radio School of the Bible had over 10,000 registrants. In 1942, WMBI claimed to broadcast its programs through 187 radio stations across the USA, Canada, China, and Latin America.

In the 1940s, MBI set up its Moody Institute of Science, distributing missionary science films to a wide audience.

At the same time, MBI carried out less-well-known distance-learning programs as well. As I discovered in the MBI archives, from the 1920s through the 1960s the Moody Literature Mission delivered millions of books and tracts to readers throughout the country and throughout the world.

The point of these distance-learning programs was always the same. MBI, like all evangelical colleges and universities, had a mission of missions. It was dedicated to training young people to carry the Gospel around the world. And, unlike some people’s image of stuffy Luddite conservatives, evangelical institutions were always pioneers in every type of technology: print, radio, film, and internet.

So when the Jerry Falwells experimented with distance education, they weren’t innovating at all, really. Rather, they were merely continuing the long tradition of evangelical higher education—using all available means to deliver the Gospel around the world.