Another prominent website in the evolution/creation debates has changed its comment policy.

As you may recall, Popular Science announced recently that it was shutting off public comments entirely. Now BioLogos has decided to vet, edit, and publish only select comments, along with author response.

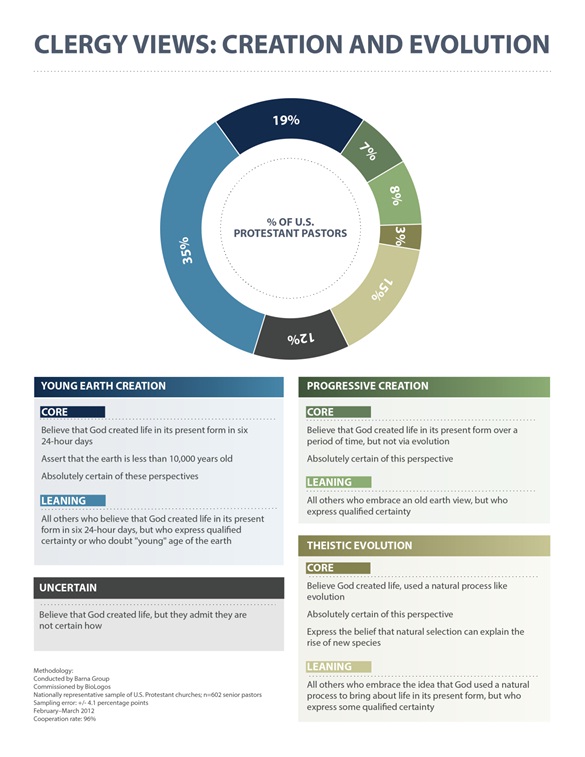

For those new to the scene, BioLogos has made itself the leading voice for theistic evolution, what its leaders often call “evolutionary creationism.” Founded by evangelical scientist Francis Collins, the organization has hoped to spread the idea that good science and good religion do not need to conflict. Bible-believing Christians, BioLogos believes, can still embrace evolutionary science.

But that does not mean, apparently, that good manners and blog commenting can go together. BioLogos’ Content Manager Jim Stump explained their reasoning for changing their public comment policy. Too much of the online discussion, Stump said, was dominated by a few voices. Instead of merely leaving comments open, editors will solicit email comments. Those comments will be organized into a more coherent back-and-forth between commenters and original authors. The hope is that this model will encourage more participation from more people than the open-forum approach.

Will it work?

If it does, is it worth the price of restricting open dialogue?

Ferocious critic Jerry Coyne called this a “desperation move” by an organization foundering on the shoals of reality. Too many commenters, Coyne argued, were asking awkward questions and making persuasive arguments. The real questions—about how God interacts with the world—proved threatening to BioLogos’ position on the compatibility of science and faith, Coyne said. Too wide a chasm yawned between real science—which recognizes the extremely unlikeliness of humanity deriving from only two people—and evangelical religion—which insists on an historical Adam & Eve.

I don’t share Professor Coyne’s contempt for the BioLogos mission. I believe the evolution/creation debates have plenty of room for scientific belief that rubs along with religious belief.

But I agree with Coyne that shutting down comments to preclude dominance by a few voices doesn’t make much sense. The purpose of this sort of online publication is precisely to allow a free flow of ideas and discussion between people who might not otherwise meet one another. If a few vociferous voices dominate that discussion, so be it.

A better way to include the unincluded would be actively to solicit short columns and opinion pieces by a wide spectrum of readers. That way, more voices could be included from people who might shy away from the hurly-burly of an active and combative open-comment forum.