It is not a happy time to be a Flame. Former student editor Will E. Young offered a blistering expose of the school’s “atmosphere of fear” in the Washington Post. Unfortunately, Young’s experience at Liberty was not a shocking departure from the history of evangelical higher ed, but rather just a new development of an ugly tradition. As Young asks plaintively,

How can a college education stifle your freedom of thought?

Unfortunately, Jerry Falwell Jr.’s dictatorial antics are nothing new. Whether Falwell realizes it or not, he is only the latest fundamentalist school leader to bolster his authority at the cost of his school’s intellectual and spiritual integrity.

Falwell adopts the Bob Jones leadership mantra: “My Way or the Highway”

Young was student editor at the Liberty student paper and experienced the full pressure of the administration’s heavy-handed regime of censorship. His faculty advisor required him to preview articles and killed any story that made Liberty or its leader Jerry Falwell Jr. look bad.

As Young explained,

when my team took over that fall of 2017, we encountered an “oversight” system — read: a censorship regime — that required us to send every story to Falwell’s assistant for review. Any administrator or professor who appeared in an article had editing authority over any part of the article; they added and deleted whatever they wanted. Falwell called our newsroom on multiple occasions to direct our coverage personally, as he had a year earlier when, weeks before the 2016 election, he read a draft of my column defending mainstream news outlets and ordered me to say whom I planned to vote for.

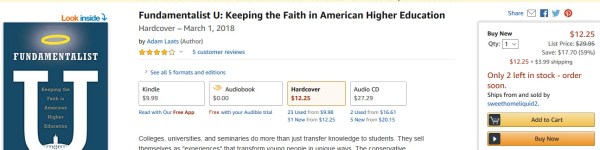

Such censorship is not new for Liberty. As we’ve seen, in recent years Liberty’s censorship has grown stricter. As I argued in Fundamentalist U, this kind of leader-focused absolutism has a long and sad tradition in evangelical higher ed. It is not a quirk of Falwell or Trumpism, but rather it is the result of the definitional problem of interdenominational evangelical higher education. Without a single, clearly defined religious orthodoxy to defend, institutions such as Liberty, Bob Jones University, and many others developed a top-down, leader-centric institutional structure. In short, lacking a denominational orthodoxy or hierarchy, some fundamentalist school leaders adopted a bitter, angry “my-way-or-the-highway” approach.

Back in the 1930s, when “fundamentalism” was still finding its legs as an institutionalized religious movement, leaders of fundamentalist colleges such as Wheaton and Bob Jones faced a dilemma. They had no universally agreed-upon definition of fundamentalism, yet they were charged with teaching fundamentalism and maintaining a purely fundamentalist campus.

Buswell at Wheaton.

Different schools reacted differently. Wheaton ended up with a confusing spread of institutional authority. Early President J. Oliver Buswell found out the hard way that he could not simply dictate policy at Wheaton. When Buswell tried to embrace a vision of fundamentalism that meant full separation from non-fundamentalist Protestants, he was summarily fired.

At the same time, Bob Jones Sr. pioneered the kind of fundamentalist leadership that is on display today at Liberty University. All faculty members were required to agree with every jot and tittle of Jones’s beliefs. One faculty member was fired in 1938 for “hobnobbing” with students. As this fired faculty member wrote in an open letter, he had worked at two other evangelical universities in his career,

two of them orthodox. (But not obnoxious.) My loyalty was never questioned . . . . It simply never occurred to me that I was not free to express my opinions and I did express them. How was I to know that loyalty meant dictatorship?

It might never have been crystal clear what “fundamentalism” meant, but at Bob Jones College (later Bob Jones University), it always meant whatever the leader said it meant. Any disagreement, any “griping,” meant a fast ticket out the door, with a furious gossip campaign among the fundamentalist community to discredit the fired faculty member.

Mr. Young’s story from Liberty U is heart-wrenching, but it is not new. The dictatorial style of Jerry Falwell Jr. is not an innovation, but rather only the sad flowering of a poisonous fundamentalist flower.