Jonathan Zimmerman says let her talk. When we defend academic speech we disagree with, we defend ALL academic speech. Jonathan Haidt says let her talk, because she’s right. Stable marriages and “bourgeois culture,” Haidt agrees, really do help people improve their economic conditions. We here at ILYBYGTH want Professor Wax to have her say for different reasons. In short, we think we won’t be able to truly reform public education until we do. We’ll make our case this morning and we’re going for bonus points by working in both creationism and the Green Bay Packers.

I don’t think St. Aaron attended Penn Law…

If you haven’t been following the frouforole emanating out of Philadelphia, here it is in a nutshell: Professor Amy Wax of Penn Law and Professor Larry Alexander of UCLA penned a provocative piece at Philly.com. If we really want to ease the burdens of poverty, they reasoned, we should encourage more people to embrace “bourgeois culture.” Such ideas have gotten a bum rap, Wax and Alexander said, but the notions of deferred gratification, stable two-parent households, and patriotic clean living are of enormous economic value.

The outcry was loud and predictable. Penn students rallied to shut down such “white supremacist” notions. Wax’s colleagues denounced her ideas in more nuanced form.

Any progressive historians in the room surely share Professor Zimmerman’s concern. After all, when academic speech has been banned and persecuted in this country, it has been progressive and leftist scholars who have borne the brunt of such punishment.

There is a more important reason to allow and encourage a frank and open airing of Professor Wax’s arguments. As recent polls have reminded us, Americans in general are profoundly divided about the meaning of poverty. For argument’s sake, we might say there are two general sides. Lots of us think that the most important cause of poverty is a social system that defends its own built-in hierarchies. Rich people stay rich and poor people stay poor. Lots of other people disagree. Many Americans tend to blame individuals for their poverty, to assume that personal characteristics such as grit and gumption are enough to solve the problem of poverty.

Professor Wax’s argument tends to support the latter view. And if you disagree with her, you might be tempted to try to shut her down.

That’s a mistake.

Why? Because her arguments just don’t hold water. And because the more often we can get discussions of poverty on the front pages, the more chances we’ll have to make better arguments, to explain that America’s anxiously held Horatio-Alger notions don’t match reality.

In other words, when it comes to tackling the problem of poverty in America, the biggest challenge is that people simply don’t want to talk about it. They want to rest in their comfortable assumptions that the system is fundamentally fair even if some people don’t have what it takes to get ahead.

I’m convinced that the truth is different. Personal characteristics matter, of course. Far more important, however, is the whole picture—the social system that puts some kids on a smooth escalator to riches and others in a deep economic pit with a broken ladder.

Because I’m convinced that the best social-science evidence supports my position, I want to hear more from people like Professor Wax. I want to encourage people who disagree to make their cases in the front pages of every newspaper in the country.

Sound nutty? Consider a couple of examples from near and far.

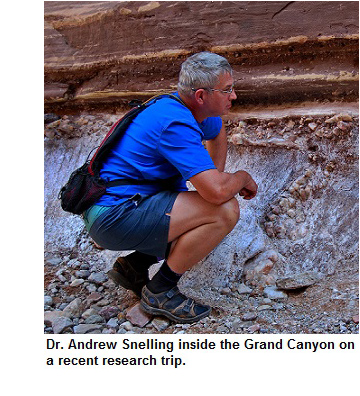

Radical creationists like Ken Ham want to protect children from the idea of evolution. They fear, in short, that students who hear the evidence for evolution will find it convincing. With a few prominent exceptions, radical creationists want to cut evolution from textbooks and inoculate students against evolution’s powerful intellectual allure.

Those of us who want to help children learn more and better science should welcome every chance to put the evidence for mainstream evolutionary theory up against the evidence for radical young-earth creationism. Mainstream science should never try to shut down dissident creationist science. That’s counter-productive. Rather, mainstream science should encourage frank and open discussions, knowing that exposure to the arguments on both sides will convince more and more people of the power of mainstream thinking.

Or, for my Wisconsin friends, consider another example.

If a Bears fan wants to clamber up on the bar and insist that her team is better than the Packers, it would be the height of folly to try to stop her from speaking her piece. Those of us who know the true saving grace of St. Aaron will instead happily let her slur through her argument, smiling and waiting for Thursday night. The more games we play, the more often the Packers will win.

When the evidence is on our side, it is always better to encourage all the debate we can get.